Role of Brand Trust in Private Label Adoption Model- an Affective and Trust-based Innovation Characteristic

Published at : 28 Jul 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 5 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i5.5935

Fong, S.W.L., Ismail, H., Kian, T.P., 2023. Role of Brand Trust in Private Label Adoption Model- an Affective and Trust-based Innovation Characteristic. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(5), pp. 993-1008

| Stany Wee Lian Fong | Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, Jalan Ayer Keroh Lama, 75450 Bukit Beruang, Melaka, Malaysia |

| Hishamuddin Ismail | Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, Jalan Ayer Keroh Lama, 75450 Bukit Beruang, Melaka, Malaysia |

| Tan Pei Kian | Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, Jalan Ayer Keroh Lama, 75450 Bukit Beruang, Melaka, Malaysia |

Consumers' lack of trust in the private label brand is thought to be the

root cause of private label's failure in developing markets, particularly in

Asia. To improve their market share in developing markets, retailers must

address private-label brand trust issues and utilize private-label

characteristics to convince non-users to adopt their products. However, brand

trust, which is understood to play a significant impact in innovation adoption,

is not taken into account in the Diffusion-of-Innovation literature. To fill

this gap, this study aims to apply a trust-based commendation to supplement

'brand trust' as the innovation characteristic and validate an adoption model

for the private label that consists of all its important innovation

characteristics. Brand trust is also expected to play a determinant role in the

innovation characteristic model as an affective-based innovation characteristic.

As a result, this study has empirically proven brand trust ( = 0.364) to be

the most influential characteristic of adoption intention compared to relative

advantage (

= 0.214), compatibility (

= 0.214), and perceived risk (

=

-0.167). The empirical support of brand trust as the affective mediator

contributes to justifying the significance of affective-based characteristics

to the adoption of innovation.

Adoption; Brand trust; Diffusion of innovation; Hierarchy of effects; Private label

Anticipated economic consequences and the rising cost of living

resulting from the coronavirus pandemic are expected to lead to a significant

increase in the number of value-minded consumers. These consumers will frequently shop at

Everyday Low Price (EDLP) stores and have an unusual propensity for being

frugal. They become more price cautious, put more emphasis on finding ways to

pay less while still receiving the goods they desire, and consequently are more

inclined to switch to less expensive options like private label goods (PLMA, 2021). Private Labels

(hereafter, PLs) are brand names created, fully owned, and controlled by

retailers to market products that are sold exclusively at their retail stores (PLMA, 2022). PLs, are frequently priced lower

than National Brands (hereafter, NBs) in a retailer's chain of stores to compete with

them under the same roof directly (Sharma et

al., 2020). Today, the quality of Private label (PL) products

is thought to have greatly improved, with the PL constituents reportedly being

on par with or even better than NBs (Olsen et

al., 2011).

The PL is

thought to have some advantages over National Brand (NB) items when the value of money is

declining as consumers desire better value and are prone to cheaper

Despite the present innovation characteristic models of

Diffusion-of-Innovation (hereafter, DOI) being considered a comprehensive,

brand trust, which is understood to play a significant impact in innovation

adoption, is not taken into account in the literature (Wu, Yang,

and Wu, 2021). In retailing, consumers commonly use the

brand name as an extrinsic cue to predict the quality of the PL, and this

formation of quality expectations based on brand name is frequently referred to

as a form of trust (Komiak and Benbasat, 2006).

The absence of brand trust in DOI is calling this study to (1) apply a

trust-based commendation to supplement 'brand trust' as the new innovation

characteristic and (2) validate an adoption model for PL that consist of all

its important innovation characteristics.

Brand trust is also anticipated to assume a determinant role in the

affective-based innovation characteristic model within the Diffusion of

Innovation (DOI) framework. When PL products are perceived as unfamiliar by

non-adopters, adoption decisions are more likely to be influenced by affective

factors rather than cognitive assessments (Komiak

and Benbasat, 2006). Brand trust is expected to play an affection role

in PL adoption as "a feeling of security" for consumers to rely on (Delgado-Ballester, Munuera-Aleman,

and Yague-Guillen, 2003). Brand

trust is deemed practically essential to retailing and serves as an affection

of satisfaction that reduces risk in the consumer purchasing process (Afzal et al., 2010), forms consumer

loyalty (Li et al., 2008), and

commitment to forging strong buyer-seller relationships (Afzal et al., 2010). Therefore, the addition of brand

trust to DOI's adoption model is expected to improve the predictive power of

adoption decisions and draw scholars' attention to the lack of trust and

affection-based innovation characteristics in the DOI literature.

Theoretical Foundations and Research Model

2.1. Private Label

PLs are the names or symbols of retailers that can be seen on the packaging

of products that are frequently sold at a certain chain of retail stores (PLMA, 2022). PLs are universally named under

store-brand and separate-brand strategies (Chou and

Wang, 2017; Sarkar, Sharma, and Kalro, 2016). Store-brand strategies typically name the PL after the real name of the

retailer, and these names include store brand, umbrella brand, own brand, and

house brand on the other hand, a separate-brand strategy, commonly known as

vice-branding or sub-branding, involves the use of a new brand name, distinct

from that of the retailer, to establish an independent and stand-alone brand

identity. Generally, PL products are made by third parties, either by exclusive

PL manufacturers who exclusively produce for retailers or by brand

manufacturers who make NBs but also use their additional production capacity to

produce PL for retailers. Only a small number of PL products are manufactured

by retailers themselves, using their own production facilities (PLMA, 2022; AAM, 2011). Retailers who fully own and control

their PLs have full control over the PLs' marketing operations, including

choosing the product's manufacturer, deciding on the brand name, setting the

product's features, pricing, and packaging design, as well as conducting

promotions and advertising (Jaafar and Lalp, 2012).

The PL

emerged as a strategic response from retailers to counter the high prices of National

Brands (NBs) (Fitzell, 1982). PLs typically

offer lower prices compared to NBs, allowing them to directly compete within

the same retail space (Sharma et al., 2020).

However, in the early 1920s, national brands' severe competition caused many

retailers to start prioritizing price over the quality of PL products (Fitzell, 1982). This price-driven marketing strategy

had reduced PL's perceived value into a low-cost image that was associated with

a low-quality image (Chou and Wang, 2017; Sarkar, Sharma, and Kalro, 2016) and did not pose a serious threat to NBs at retail

outlets (Sutton-Brady, Taylor, and Kamvounias, 2017).

Today,

PL products are thought to be of substantially higher quality, with PL

constituents allegedly being on par with or even superior to NBs (Olsen et al., 2011). This explains that PL

and NBs are physically equivalent, and their quality is acceptable from a

physical viewpoint. Consumers in developing countries, however, do not appear

to be able to recognize the benefits of PL over NB. The poorer PL market share

in the developing market indicates a lack of trust towards the brand name of

PL, which leads to a poorer perception of the quality of PL products and

results in higher rejection among consumers. It is thought that PL product

rejection occurs even before PL testing or use. In other words, buyers might

not have even tried PLs before simply rejecting them based on perception. This

emphasizes how novel PLs are to the majority of customers in developing

markets, where PLs are perceived as a novel, unfamiliar concept with little

understanding and information to them. As a result, this study highlights the

need to investigate PL from the perspective of DOI to comprehend how consumers

view PL as an innovation.

Conceptually, PL aligns with Rogers

(2003) notion of innovation within the context of DOI. According to Rogers (2003), the determining factor for an

innovation is not its duration but rather the perceived originality of the

innovation by the potential user. PL is viewed as unique or unusual in retailing,

particularly in developing markets. This low market share illustrates how PL is

not widely used in developing markets, as it is seen as a novel concept with

limited acceptance and knowledge among the local community. where its average

volume share is still below the cut-off point of 5%. (Oracle,

2020). Conceptually, this supports the idea that PL is an innovation in

a developing market.

2.2. Diffusion of Innovation: Innovation

Characteristics

The

Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) is a well-known social science theory that seeks

to explain how and why new ideas are embraced by people and how rapidly they

spread among them within a community (Rogers, 2003).

The foundational DOI literature is credited to Everett Rogers

(1958), which listed five essential characteristics of an innovation

that can accelerate or slow the innovation's market acceptance, namely:

relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability.

These innovation characteristics or attributes are said to be crucial to a new

product and the social system as these characteristics contribute 49 to 87

percent to the rate of innovation adoption (Rogers,

1995). The "innovation characteristic studies" are crucial for

anticipating how people will react to a novel innovation. With the aid of these

predictions, marketers can alter the names and positions of innovations as well

as how they relate to potential adopters' pre-existing beliefs and experiences (Rogers, 2003).

Over the past 50 years, Rogers' original

characteristic framework has been expanded to become one of the most

comprehensive in the marketing literature (Flight, D’Souza, and Allaway, 2011).

Successive DOI research subsequently concentrated on analyzing the roles played

by these characteristics and exploring brand-new variables that influence the

rate of innovation adoption, such as perceived risk (Ostlund,

1974; Bauer, 1960), status

conferral (Holloway, 1977), cost,

communicability, divisibility, perceived cost, social approval, and

profitability (Tornatzky and Klein, 1982);

the image or social approval and voluntariness (Moore

and Benbasat, 1991); perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Davis, 1986) and purchase context, supplier

characteristics, and product usage (Shaw, Giglierano, and Kallis, 1989; Dickson 1982; Leigh and Martin, 1981).

The

adaptation of the existing innovation characteristic model to the PL context

pinpointed the absence of 'affective-based' and 'trust-based' innovation

characteristics in DOI literature. Based on the summary of Flight, D’Souza,

and Allaway (2011), there is

an indication of cognitive orientation in the innovation characteristic studies

where common characteristics such as compatibility, relative advantage, and

risk/complexity are commonly conceptualized as cognitive constructs in the

marketing literature (e.g. Komiak and Benbasat,

2006; Parthasarathy et al., 1995). Decisions made by consumers,

especially in deciding PL adoption, seem to be certainly influenced by

"affective" characteristics: (1) The human experience includes both

cognitive and emotional aspects (Komiak and

Bensabat, 2006); (2) The Rational Choice Theory states that customers'

conscious decisions frequently involve both reasoning and feeling; (3) Consumer

decision-making is less likely to be cognitively dominant since consumers are

unfamiliar with the innovation (Jiang and Benbasat,

2004); and (4) Consumers' affective response to the innovation has an

impact on their choices, therefore adopting the innovation may not be a

completely cognitive decision (Derbaix, 1995).

On the

other hand, the lack of trust-based innovation characteristics can be explained

by consumers' formation of quality expectations towards the innovation. In DOI,

potential adopters are thought to experience difficulties due to the novelty of

innovations, including their inability to evaluate the innovations' intrinsic

qualities (such as features, quality, and performance) and their difficulty

determining whether the innovations can meet their needs (Rogers, 2003). Thus, potential adopters are

driven to form quality expectations based on the external characteristics of

the innovation, including their trust in the seller's reputation and brand name

(Chocarro, Cortiñas, and Elorz, 2009; Speed, 1998). In

marketing literature, this formation of quality expectations based on extrinsic

features is frequently referred to as a form of trust, which is characterized

as a state of dependence between two parties when risk is present (Komiak and Benbasat, 2006). When a potential

adopter (the trustor) can predict the behavior of the trustee (the innovation

seller) in the future through the knowledge of the trustee (the innovation

seller), trust has been established (Gefen, Karahanna, and Straub, 2003). As a result, the innovation adoption decision will be heavily

influenced by the degree of trust a potential adopter has in the brand or

seller of the innovation.

2.3. Brand Trust as the New Trust and Affective

Innovation Characteristic

Brand trust is described

as a "consumer's feeling of security" during engagement with the

company, essentially perceiving the brand as trustworthy and accountable for

consumers' interests and welfare (Delgado-Ballester, Munuera-Aleman, and Yague-Guillen, 2003). Brand trust is also linked to

"confidence expectations" regarding the brand's dependability and

intentions, where it is seen as a form of confidence in taking a risk by

relying on the brand of another party (Afzal et al., 2010). When forming expectations and evaluating the quality of a product,

consumers look to the brand as a quality signal (Lassoued

and Hobbs, 2015). Credibility is expected to contribute to consumers'

trust in a brand and serve as a determinant of their confidence in the quality

attributes, particularly when they face a lack of sufficient information during

the purchasing decision-making process. Consumer commitment to a brand can

result from their initial trust in the brand evolving into confidence in its

brand performance as they use its products (Lassoued

and Hobbs, 2015).

Innovation adoption depends heavily on

brand trust. Adoption, which is linked to the adopter's repetitive usage

behavior (Schiffman and Wisenblit, 2015), is

frequently conceptually equated with loyalty. Given that brand loyalty is

frequently suggested as a brand trust's indirect effect, it makes sense to

infer that brand trust has an impact on adoption behavior (Lassoued and Hobbs, 2015). Consumers' intentions

for future adoption are anticipated to be determined by brand trust, which will

also influence their decision-making. As a result, confidence arises from the

great experience and ongoing satisfaction that support customer loyalty and

recurrent brand usage (Lassoued and Hobbs, 2015).

When PL appears to be the innovation under study, it is believed that its brand

will have a certain influence on consumers' anticipation of what they can

expect from a specific brand of PL product. The brand of PL becomes even more

crucial for customers to infer its product quality because most PL products are

offered in the experiential goods category, where their features can only be

judged after consumers begin to consume (Smith and

Johnson, 2022; Nelson, 1974).

On the other hand, since most PL

products are named after the retailer's existing brand name, the PL brand

symbolizes the overall consumer view of the retailer and frequently serves as a

cue of expectation for a particular PL product. In this study, brand trust is

seen as an affective construct for three reasons. First, brand trust is defined

as a form of "consumer feeling of security" when interacting with the

brand (Delgado-Ballester, Munuera-Aleman,

and Yague-Guillen, 2003).

Second, brand trust is also regarded as a manifestation of "consumer

affective assessment," which elucidates consumers' willingness to depend

on a brand in order to receive the promised benefits (Komiak

and Benbasat, 2006). Third, brand trust is described as an

"emotional condition" that includes a consumer's willingness to be

conscious of vulnerability in response to the intentions or actions of other

parties (Afzal et

al., 2010). Due to PL's unfamiliarity with most

consumers in developing markets, the PL adoption decisions are thought to be

more likely to be based on affective than on cognitive assessment and this

further supports the affective conceptualization of brand trust in the context

of PL adoption (Chocarro, Cortinas, and Elorz, 2009). Consumers will become committed to the brand and feel secure enough

to take the risk of depending (Lewis and Weigert,

1985) on the PL brand if they have a positive perception of its reliability

and integrity (Afzal et al., 2010).

Therefore, it is assumed in this study that "the more trustworthy of the

brand, the more likely it is that consumers will adopt PL."

Research

Model and Hypotheses Development

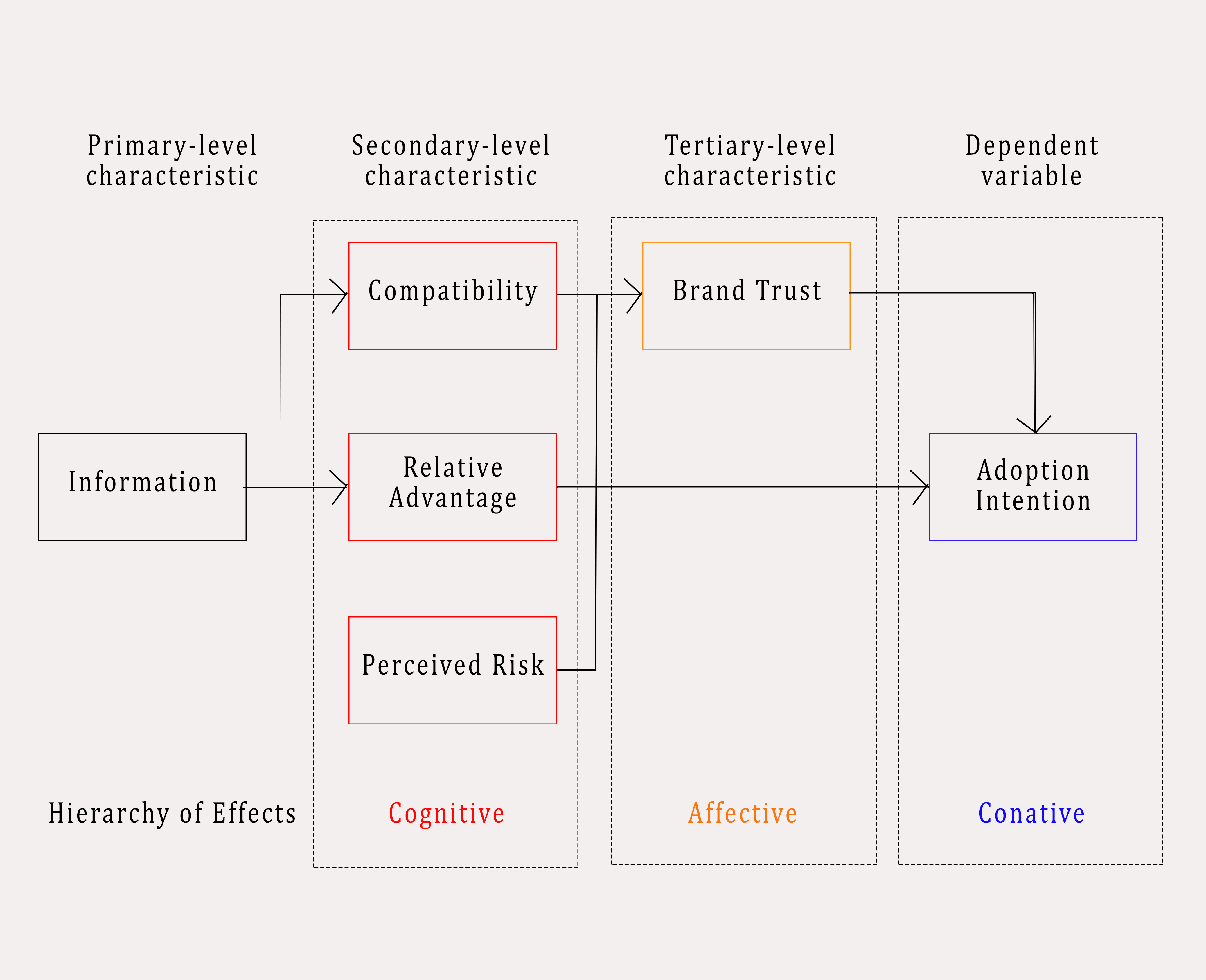

The model of this

study (Figure 1) is concluded with five innovation characteristics-

information, compatibility, relative advantage, perceived risk, and brand

trust. Drawing the theoretical foundation from the Hierarchy

of Effects model (hereafter, HOE) and the functional-level recommendation of Flight, D’Souza,

and Allaway, (2011), this

study applied three functional levels of innovation interpretation to

conceptualize the innovation characteristics into cognitive, affective, and

conative stages based on the HOE model's "think-feel-do" chain: (1)

information construct as a primary-level characteristic which works as the

trait that universally recognized across all potential users; (2)

compatibility, relative advantage, and perceived risk as the secondary-level

cognitive-based constructs that explain the mental or rational state of

innovation assessment that uniquely perceived across all potential adopters;

(3) brand trust as tertiary-level affective-based construct that explains the

emotional or feeling state of innovation assessment; and (4) adoption intention

conceptualized as a conative construct that works as the target behavior of

this study.

The

information construct originated from the trialability, communicability, and

observability characteristics and is posited on the idea that potential

adopters learn about the innovation from their internal and external

communication channels rather than the usual sources of information covered in

marketing literature. To ease the diffusion of information, the innovation

itself is expected to contain characteristics that aid the flow of its

information to potential innovation adopters (Flight, D’Souza, and Allaway, 2011; Parthasarathy

et al., 1995). In the PL context, the dissemination of PL

information is essential for consumer adoption as it influences customer

awareness and decision-making about whether it is worthwhile to try unfamiliar

PL products. PL products with higher transmit-ability enable consumers to (1)

be assured that the PL product fits their lifestyles (Holak

and Lehmann, 1990); (2) perceive higher advantages in the PL compared to

the current brand used (Flight, D’Souza, and Allaway, 2011); and (3)

disregard any concerns about the PL products (Beneke

et al., 2012; Hirunyawipada and Paswan, 2006). Thus, this study

proposes the following three hypotheses:

H1: Information

is positively related to the compatibility of PL products.

H2: Information

is positively related to the relative advantage of PL products.

H3: Information

is negatively related to the perceived risk of PL products.

The compatibility construct refers to the

degree to which an innovation fits into the social and personal structures of

potential adopters (Flight, D’Souza, and Allaway, 2011). When

compatible, the innovation is deemed to reduce adopters' level of uncertainty

and typically fits well with the situations of potential adopters (Rogers, 2003). This situational fit is also

linked to (1) an innovation's conformity to the cultural norms of the social

system to which the potential adopter belongs (Sitorus

et al., 2019); and (2) the consistency of the innovation with the

needs and adopted ideas of the potential adopter (Jaakkola

and Renko, 2007; Rogers, 2003). The adoption of PL can be associated

with consumers' natural resistance to change, where new products or brands that

do not match the present habit are likely to be rejected. It is believed that

greater compatibility makes the PL product less ambiguous for consumers and

typically fits the circumstances of potential adopters, which directly

encourages the adoption of the PL brand or product (Rogers,

2003). Thus, this study proposes the following 4th hypothesis:

H4: Compatibility is positively related to the

adoption intention of PL products.

Relative advantage is the perceived

benefit that the innovation can provide over the alternatives now available to

the adopter or how the innovation is viewed as being superior to the idea it

replaces (Jo Black et al., 2001; Hansen, 2005; Rogers, 2003). It is

evaluated based on the perceived benefits that an adopter will derive from the

innovation in comparison to the product they are currently using. Typically,

the innovation's nature dictates the exact type of relative advantage that

potential adopters would focus on, such as the benefits of economic, social,

and so on (Rogers, 2003). In the PL context,

the relative advantage is commonly assessed based on the value comparison

between the PL product and the current adopted brand. Prior PL studies suggested

two key relative advantages: economic advantage (e.g.

Beneke et al., 2012) and products' performance and consistency (e.g. Richardson, Jain, and Dick, 1996). When

the advantage of the PL is perceived to be greater than the current brand alternatives,

the adoption is said to be more likely to happen. Thus, the 5th hypothesis of

this study is proposed as follows:

H5: Relative advantage is positively related

to the adoption intention of PL products.

This study denotes perceived risk to Rogers (2003) complexity characteristic, which is

focused on 'the uncertainty induced from the physical product,' such as the

performance risk, physical risk, and risk from the product category. In the

context of DOI, innovation seems unusual and novel to potential customers and

reflects low familiarity with the innovation. Thus, it is common to see

consumers assessing the possibility of innovation failure when they are not

familiar with the new idea (González Mieres, María Díaz Martín, and Trespalacios

Gutiérrez, 2005; Ong et al., 2022). PL product is often

associated with perceived risk, as PL products were previously associated with

low pricing, inferior quality, and poor performance (Beneke

et al., 2012). PLs are often perceived as high-risk purchases,

and customers are hesitant to take on the financial or physical risks

associated with using PL products (Mostafa and

Elseidi, 2018; Nielsen, 2014).

Thus, the 6th hypothesis of this study is proposed as:

H6: Perceived risk is negatively related to

the adoption intention of PL products.

The absence of trust-based

characteristics in DOI literature called for the brand trust to be supplemented

as the innovation characteristic of the new PL adoption model. Brand trust is

said to be long recognized in marketing and psychology literature, where it is

seen as a type of bonding where one believes in another (LaFollette, 1996) and essential for consumers in setting

expectations and assessing the quality of a product (Candra, Nuruttarwiyah, and Hapsari, 2020; Lassoued and Hobbs, 2015). Today, practically

all products are advertised using a brand, and the impact of brand trust in

most contexts of customer behavior is somehow indisputable. Since PL is

unfamiliar to the majority of consumers in developing markets, its brand has

typically developed into a crucial quality indicator to help consumers in

making purchase decisions (Chocarro, Cortinas, and

Elorz, 2009; Mitra, 1995), and it indicates what consumers can expect from

a particular product (Chocarro, Cortiñas, and Elorz, 2009). Therefore, this study presumes that:

H7: Brand trust is positively related to the

adoption intention of PL products.

In most adoption contexts, the dependence

of consumer choice on "affective" characteristics appears to be

unavoidable. This is doubly important for a "brand-based" innovation

like PL, which denotes the dependence of consumer evaluation on the

trustworthiness of the retailer's brand before adopting PL products. The

proposed mediation effect of brand trust in the PL adoption model is justified

as when consumers believe PL to be superior to the brand being replaced (in

terms of compatibility, relative advantage, and risk), this cognitive

assessment is said to be capable of delivering them a "feeling of

security" to rely on PL brand, and eventually, adopt the PL products. By

proposing 'brand trust' as an affective-based characteristic to mediate the

cognitive-based constructs and dependent variable, this study proposes:

H8:

Brand trust mediates

compatibility to the adoption intention of PL products.

H9: Brand trust mediates relative advantage to

the adoption intention of PL products.

H10: Brand

trust mediates perceived risk to the adoption intention of PL products.

Figure 1 The research model

With the support of

relevant literature, multiple innovation characteristics were identified to

examine the adoption intention of retailer shoppers towards PL products. The

applicability of these characteristics and their items in the context of the PL

products was then further validated by five marketing academicians and one

industry expert in the retail and branding industry. As a result, five

innovation characteristics of PL products- information, compatibility, relative

advantage, perceived risk, and brand trust were chosen as the final constructs

formatively measured by twelve closed-ended indicators (listed in Table

1). These indicators are measured using

metric interval scales, with a summated rating or a five-point Likert scale

employed to gauge respondents' beliefs and intentions regarding PL products.

The data required for analysis were gathered using a

quantitative approach. The survey technique was applied with a questionnaire as

the instrument to collect data from 270 retail shoppers who had yet to adopt PL

products, as the data on the innovation characteristics are said to be valuable

only when it is collected before or concurrently with the adoption decision of

the respondents (Rogers, 2003). These

respondents were intercepted in nine retail outlets in Malaysia with the hybrid

sampling method (cluster and convenience sampling). To ensure the

representativeness and eligibility of the respondents, four filtering questions

were included in the questionnaire to determine the user status of the

respondents towards PL products.

Data Analysis

PLS-SEM (also termed PLS path modeling) has

been chosen as the data analysis method, and the SmartPLS 3.3.3 analytical

software is used to analyze and answer the hypotheses of this study.

5.1 Demographic Profiling

270 qualified respondents participated in this

study. Prior to data submission, each questionnaire was carefully reviewed to

ensure that all questions had been addressed and all respondents fulfilled the

"novelty" criteria towards PL products in retail stores they visit.

Among the 270 respondents, 157 (58.15 %) are reported as males, and 113 (41.85 %)

are females. The majority of the respondents fall in the age group of 31 to 40

years old (27.04 %), followed by 41 to 50 (24.44 %), 61 and above (16.67 %), 51

to 60 (15.56 %), 21 to 30 (12.22%), and below 21 years old (4.07%). In the

context of academic qualification, 16 (5.93 %) with qualification of PMR or

lower, 90 (33.33 %) with SPM / O-level qualification, 24 (8.89 %) with

STPM/A-Level qualification, 75 (27.78 %) with Diploma qualification, 56 (20.74 %)

with Bachelor Degree qualification, and 9 (3.33 %) with qualification of Master

Degree and above. As for monthly personal income, the majority of the

respondents (37.04 %) are recorded with income lower than RM3000, 39.26% with

income ranging from RM3000 to RM4999, 12.96 % with income ranging from RM5000

to RM6999, and 10.74% with income RM7000 and above.

5.2. Measurement Model

As illustrated in Table 1, all constructs of

the model have been reported to meet the formative measurement model's

evaluation requirements: convergent validity, collinearity assessment, and

significance and relevance of outer weights. As for the convergent validity,

all five constructs have achieved the 0.7 thresholds for the path coefficient

values (Hair et al., 2017) with

information at 0.720, compatibility at 0.781, relative advantage at 0.707,

perceived risk at 0.918, and brand trust at 0.906. All 12 indicators have

obtained the desired level of VIF values lower than 5.0, as stated by Hair et al. (2017). Hence there is no

collinearity problem in the model. Lastly, all 12 indicators are recorded with

outer weights or outer loadings significant at p < 0.05 threshold and deemed

to be important to the formation of five constructs of the model:

communicability (outer weight = 0.618, p < 0.01), observability (outer

weight = 0.520, p < 0.01), trialability (outer loading = 0.4858, p <

0.01), personal compatibility (outer weight = 0.519, p < 0.01), social

compatibility (outer weight = 0.625, p < 0.01), relative product performance

(outer weight = 0.833, p < 0.01), relative economic advantage (outer weight

= 0.306, p < 0.01), performance risk (outer weight = 0.679, p < 0.01),

physical risk (outer weight = 0.849, p < 0.05), category risk (outer weight

= 0.673, p < 0.05), brand competence (outer weight = 0.305, p < 0.05),

and brand intention (outer weight = 0.738, p < 0.01). Thus, all twelve

indicators are detained in the model for further analysis and implementation.

Table 1 Result summary for the

formative measurement model

5.3. Structural Model

In the structural model, the

criteria for collinearity assessment is fulfilled with all constructs' VIF

values below the 5.0 threshold- compatibility VIF value at 1.621, relative

advantage VIF value at 1.894, perceived risk VIF value at 1.091, and brand trust

VIF value at 1.700 indicating no lateral multicollinearity concern.

T-statistics for the seven direct paths of the model have been generated using

the SmartPLS 3.3.3 bootstrapping method to evaluate the significance level of

relationships. As illustrated in Table 2, six direct relationships have

t-values that are equal or large to 1.96, making them significant at the 0.05

level of significance: information to compatibility with the recorded t-value

of 11.66 (p < 0.01), information to relative advantage with t-value = 9.20

(p < 0.01), compatibility to adoption intention with t-value = 3.46 (p <

0.01), the relative advantage to adoption intention with t-value = 3.16 (p <

0.01), perceived risk to adoption intention with t-value = 3.32 (p < 0.01),

and brand trust to adoption intention with t-value = 5.67 (p < 0.01).

However, the direct relationship path from information to perceived risk is

reported to be insignificant at 0.05 level, with the t-value recorded at 0.886

(p > 0.05). Thus, the hypotheses testing of this study is concluded with

hypotheses H1, H2, H4, H5, H6, and H7 supported, whereas hypothesis H3 is not

supported.

Tabel 2 Hypotheses testing

On the other hand, the three mediation hypotheses for brand trust (as

illustrated in Table 3) are answered with (1) Hypothesis H8 supported with

standardized beta recorded as 0.070, t-value of indirect effect as 2.264 (p

< 0.05) and direct effect reported as 3.461 (p < 0.05) indicating a

complementary mediation of brand trust in compatibility to adoption intention,

(2) Hypothesis H9 supported with standardized beta recorded as 0.164, t-value

of indirect effect as 3.514 (p < 0.05) and direct effect reported as 3.164

(p < 0.05) indicating a complementary mediation of brand trust in relative

advantage to adoption intention, and (3) Hypothesis H10 supported with

standardized beta recorded as -0.066, t-value of indirect effect as 2.406 (p

> 0.05) and direct effect reported as 3.320 (p < 0.05) indicating a

competitive mediation of brand trust in perceived risk to adoption intention.

The R2 value of the dependent variable in the model indicates a moderate level

of predictive accuracy (Hair et al., 2014), with brand trust,

compatibility, relative advantage, and perceived risk carrying 53.31% of

overall influences on adoption intention. Brand trust (f2 = 0.167) is reported

to have medium and larger effect sizes towards the adoption intention compared

to compatibility (f2 = 0.061), relative advantage (f2 = 0.052), perceived risk

(f2 = 0.054) and indicating brand trust plays a stronger influence on adoption

intention compared to the conventional innovation characteristics in PL

context.

Tabel 3 Significance analysis of direct and indirect effects of brand trust

5.4. Result

Discussion

Empirically, this study has

filled the gap in traditional DOI studies by highlighting the need for

'trust-based' and 'affective-based' characteristics in the characteristic

adoption model and distinguishing the model of this study from the conventional

adoption models. 'Brand trust' (= 0.364), which is often neglected in DOI

literature, is empirically proven to have a stronger influence on the adoption

intention than the conventional innovation characteristics: relative advantage

(

= 0.214), compatibility (

C = 0.214), and perceived risk (

= -0.167). This

result has somewhat proven that non-adopters are giving the

"affective-based" characteristic more attention than the traditional

"cognitive-based" attributes. Additionally, brand trust's empirical

support for mediating compatibility (

= 0.070), relative advantage (

= 0.164), and perceived risk (

= -0.066) to adoption

intention has emphasized the importance of affective-based characteristics to

the adoption intention and supported the conceptualization of brand trust as

the "affective" characteristic.

However, the insignificance

influence of information on perceived risk (t = 0.886; p > 0.05) is rather

unforeseen as past literature, such as Conchar et

al. (2004) and Holak and Lehmann (1990),

support a negative relationship. This insignificant relationship can possibly

be justified by the target respondents' unfamiliarity with the PL products. In

the DOI context, adoption decisions are often associated with novel products or

ideas, and this novelty is thought to create anxiety in consumers. Despite the availability of information and

knowledge, consumers are believed to experience psychological stress due to the

uncertainties surrounding innovation (Kwon, Lee, and Kwon, 2008). This psychological stress

is believed to cause consumers to forget the information they own to review the

innovation (Kwon, Lee, and Kwon, 2008). As a result, consumers are

found to ignore search-based information such as advertisements, word-of-mouth,

or short-term trial results (Vengrauskas, 2012)

until they receive experience-based information, which is post-adoption

information gained from actual product usage (Vengrauskas,

2012).

Recommendation and Future Research

6.1.

Marketing Implications for Private Label Products Adoption

The misperception about PL products and

their low market share rate in developing markets suggest retailers learn how

consumers perceive the characteristics of PL products as an innovation and

determine which characteristics inspire them to commit. Based on the empirical

findings, this study ought to recommend several implications that retailers can

use to strategically plan their PL offerings. Firstly, it is essential for

retail managers to be aware that consumers' decision to adopt PL products can

be influenced by their perception of the retailer's trustworthiness, which is

often reflected in the retailer's brand. This highlights the importance of PL

pre-launch campaigns to retailers, where investments in brand name capital via

branding policies and ethical protocol are deemed to be critical to the success

of PL acceptance. To develop a strong brand reputation and image, retailers

must execute marketing activities and decisions based on brand rather than a product

line. These pre-launch initiatives are

thus expected to enhance consumer confidence in PL products, leading to

long-term commitment from the consumers .

Second, retail managers are recommended

to begin their PL product offerings with minimal complexity products. With

brand trust mediating compatibility and relative advantage to PL adoption,

these uncomplicated PL features will make it easier for customers to evaluate

PL's compatibility and relative advantage, which will ultimately lead to higher

trust in the PL brand. Additionally, these PLs with simple characteristics not

only mitigate the perceived risks for customers but also facilitate the broader

dissemination of PL's advantages to others.

Eventually, after PL gained the majority acceptance in the market,

retailers may then venture into higher complexity product offerings. Finally,

this study urges retailers to carefully manage the information flow on their PL

products. The promotion campaign of PL ought to place more emphasis on

demonstrating how these products fit into local lifestyles and how superior

they are to other product brands in their store. Furthermore, as perceived risk

is empirically shown to be unaffected by information, retail managers can use

"risk-reduction practices" rather than "risk-reduction

marketing", such as satisfaction assurances, product warranties, and

after-sale services to lower consumers' perceptions of risk.

Although

the affective-based innovation

characteristics have struggled to keep up with the overall adoption diffusion

literature, the reliance of consumer choice on brands as an emotional

attachment is in some ways inevitable. Retailers must understand how to address

the PL trust issue, comprehend how to persuade non-PL adopters to switch

brands, and construct their PL marketing strategies around the innovative

characteristics to increase PL market share. This adoption model will serve as

a starting point for academic researchers, particularly diffusion researchers,

to pay attention to both cognitive and affective-based constructs in

determining consumers' long-term commitment to a brand. With brand trust

literately supported in influencing consumers' purchase behavior, the inclusion

of brand trust into DOI's characteristic adoption model is deemed to be an enhancement

to the predictive power of adoption decision.

6.2.

Limitation of Study and Direction for Future Research

Due to the imbalance in PL

offering across Malaysian retailers, this study generalized PLs as frequently

bought FMCG and grocery items commonly found on the shelf of standard

hypermarkets. This low-involvement classification of PL may have restricted the

straight application of this adoption model to other technical and non-grocery

product categories. Furthermore, the emphasis of this study is on the

'characteristics of innovation’ and has excluded factors that are not related

to the innovation (the product) itself, where factors such as adopter and

social system characteristics are considered critical to the diffusion of new

ideas remain unexplored in this study. This PL product characteristic-adoption

model may only apply to non-PL adopters, who are primarily covered in

developing markets where data is gathered. This model is thought to be

ineffective at forecasting the behaviors of ex and existing adopters with prior

PL consumption experience.

Continued study of innovation characteristics is necessary. Researchers

can further specify innovation characteristics using the scales established

here, giving practitioners the advantage of knowing which characteristics most

significantly influence the diffusion curve of innovation. Once perceived

innovative aspects are considered, the actual dissemination of various products

and services can be more clearly understood. With this knowledge, practitioners

could more correctly forecast how innovation would spread and, as a result,

potentially make better marketing decisions. Considering the future expansion

of PL products to other higher-involvement product categories, future research

can investigate consumer trust in the name of the manufacturer.

High-involvement categories such as pharmaceutical products are often perceived

as high-risk purchases, and consumer confidence in these products can be

enhanced by the reputation and brand name of the manufacturer. Future research can also look at the influence of

a subject's adoption experience in assessing perceived risk. The root causes of

uncertainty, which are frequently cited as one of the hurdles to the adoption

of innovations, can be better understood by diffusion experts with the aid of

this knowledge. Lastly, the introduction of affective-based innovation

characteristics to the DOI research framework is expected to draw scholars’

attention as extrinsic and affective innovation characteristics have struggled

to keep up with the overall adoption diffusion literature due to its lack of

extensive scale of measurements.

This study was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) with project code: FRGS/1/2020/SS01/MMU/03/11.

Afzal, H., Khan, M.A., Rehman, K., Ali, I., Wajahat, S., 2010. Consumer’s

Trust in the Brand: Can It be Built through Brand Reputation, Brand Competence,

and Brand Predictability. International Business Research, Volume. 3(1), pp. 43–51

Asset Allocation and Management (AAM), 2011. Private

Label (Generic) vs Branded Products: Differences Aren’t Black and White Anymore. Available online at:

https://www.aamcompany.com/insight/private-label-generic-vs-branded-products-differences-arent-black-and-white-anymore, Accessed on January 18, 2022

Aw, E.C.-X., and Chong, H.X., 2019.

Understanding Non-private Label Consumers’ Switching Intention in Emerging Market. Marketing

Intelligence and Planning, Volume 37(6), 689–705

Bauer, R.A., 1960. Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking. In: Hancock, R.S.,

(ed.), Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World, Proceedings of the 43rd.

Conference of the American Marketing Association, p. 389

Beneke, J., Greene, A., Lok, I., Mallet, K., 2012. The

Influence of Perceived Risk on Purchase Intent-the Case of Premium Grocery

Private Label Brands in South Africa. Journal of Product and Brand

Management, Volume 21(1), pp. 4–14

Candra, S., Nuruttarwiyah, F., Hapsari, I.H., 2020. Revisited

the Technology Acceptance Model with E-trust for Peer-to-peer Lending in

Indonesia (Perspective from Fintech Users). International Journal of

Technology, Volume 11(4), pp. 710–721

Chocarro, R., Cortiñas, M., Elorz, M., 2009. The Impact of Product Category Knowledge on Consumer Use of Extrinsic Cues–a Study Involving Agrifood Products. Food

Quality and Preference, Volume 20(3), pp. 176–186

Chou, H.Y., Wang, T.Y., 2017.

Hypermarket Private-label Products, Brand Strategies and Spokesperson Persuasion. European

Journal of Marketing, Volume 51(4), 795–820

Conchar, M.P., Zinkhan, G.M., Peters, C., Olavarrieta, S., 2004. An Integrated Framework for the

Conceptualization of Consumers’ Perceived-risk Processing. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, Volume 32(4), pp. 418–436

Davis, F.D., 1986. A Technology

Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End User Information Systems:

Theory and Results. Ph.D. dissertation, Sloan School of Management,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Delgado-Ballester, E., Munuera-Aleman, J.L., Yague-Guillen, M.J., 2003. Development and Validation of a Brand Trust Scale.

International Journal of Market Research,

Volume 45 (1), pp 35–54

Derbaix, C.M., 1995. The Impact of

Affective Reactions on Attitudes towards the Advertisement and the Brand: A

Step towards Ecological Validity.

Journal of Marketing Research, Volume 32(4), pp. 470–479

Dickson, P.R., 1982. Person-situation:

Segmentation’s Missing Link. Journal of Marketing, 46(4), 56–64

Fan, S.M., 2014. Big Channel Brands Fight Using Private Labels: 72 Per Cent of Respondents Care Most About Price. Available online at:

www.cardu.com.tw/news/detail.php?nt_pk?6&ns_pk?24833, Accessed on November 06, 2022

Fitzell, P.B., 1982. History of Private

Labels. In: Private Labels: Store Brands and Generics Products, Avi

Publishing Company, pp. 27–60

Flight, R.L., D’Souza, G., Allaway, A.W., 2011.

Characteristics-Based Innovation Adoption: Scale and Model Validation. Journal

of Product and Brand Management, 20(5), pp. 343–355

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., Straub, D.W., 2003. Trust and

TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. Management Information Systems

Quarterly, Volume 27(1), pp. 51–90

Gonzalez Mieres, C., María

Díaz Martín, A., Trespalacios Gutierrez, J.A., 2005. Antecedents of the

Difference in Perceived Risk Between Store Brands and National Brands. European

Journal of Marketing, Volume 40(1/2), pp. 61–82

Hair,

J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M., 2014. A Primer on Partial

Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), SAGE Publication

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., 2017. A Primer

on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), Sage Publication

Hansen, T., 2005. Consumer Adoption of

Online Grocery Buying: A Discriminant Analysis. International Journal of

Retail and Distribution Management, Volume 33(2), pp. 101–121

Hirunyawipada, T, Paswan, A.K., 2006. Consumer

Innovativeness and Perceived Risk: Implications for High Technology Product

Adoption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, Volume 23(4), pp. 182–198

Holak, S.L., Lehmann, D.R.,

1990. Purchase intentions and the dimensions of innovation: an exploratory

model. Journal of Product Innovation and Management, Volume 7(1), pp. 59–73

Holloway, R.E., 1977. Perceptions of an Innovation: Syracuse University’s

Project Advance. Ph.D. dissertation, Syracuse University

Jaafar, S.N. and Lalp, P.E., 2012.

Consumers’ Perception towards Extrinsic and Intrinsic Factors of Private Label

Product in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. In: UMT

11th International Annual Symposium on Sustainability Science and Management,

09th – 11th July 2012, Terengganu, Malaysia

Jaakkola, E., Renko, M.,

2007. Critical Innovation Characteristics Influencing the Acceptability of a

New Pharmaceutical Product Format. Journal of Marketing Management,

Volume 23(3-4), pp. 327–346

Jiang, Z., Benbasat, I.,

2004. Virtual Product Experience: Effects of Visual and Functional Control on

Perceived Diagnosticity in Electronic Shopping. Journal of Management

Information Systems, Volume 21(3), pp. 111–147

Jo Black, N., Lockett, A.,

Winklhofer, H., Ennew, C., 2001. The Adoption of Internet

Financial Services: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Retail and

Distribution Management, Volume 29(8), pp. 390–398

Komiak, S., Benbasat, I.,

2006. The Effect of Personalization and Familiarity on Trust and Adoption of

Recommendation Agents. Management Information Systems Quarterly, Volume

30(4), pp. 941–960

Kwon, K.-N., Lee, M.-H.,

Kwon, Y.J., 2008. The Effect of Perceived Product Characteristics on Private

Brand Purchases. Journal of Consumer Marketing, Volume 25(2), pp. 105–14

LaFollette, H., 1996.

Personal Relationship: Love, Identity, and Morality. In: Cambridge, MA: Blackwell

Publisher

Lassoued, R., Hobbs, J.E.,

2015. Consumer Confidence in Credence Attributes: The Role of Brand Trust. Food

Policy, Volume 52, pp. 99–107

Leigh, J.H., Martin, C.R., 1981. A Review of

Situational Influence Paradigms and Research. In: Review of Marketing, pp. 57–74

Lewis, J.D., Weigert, A.,

1985. Trust as a Social Reality. Social Forces, Volume 63(4), pp. 967–985

Li, F., Kashyap, R., Zhou,

N., Yang, Z., 2008. Brand Trust as a Second Order Factor: An Alternative

Measurement Model. International Journal of Marketing Research., Volume

50(6), pp. 817–830

Mitra, A., 1995. Price Cue

Utilization in Product Evaluations: The Moderating Role of Motivation and

Attribute Information. Journal of Business Research, Volume 33, pp.

187–195

Moore, G.C., Benbasat, I.,

1991. Development of an Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an

Information Technology Innovation. Information Systems Research, Volume

2(3), pp. 192–222

Mostafa, R.H.A., Elseidi, R.

I., 2018. Factors Affecting Consumers’ Willingness to Buy Private Label Brands

(PLBs) Applied Study on Hypermarkets. Spanish Journal of Marketing,

Volume 22(3), 338–358

Nelson, P., 1974.

Advertising as Information. Journal of Political Economy, Volume 82(4),

729–754

Nielsen, 2014. The State of

Private Label Around the World, Where it’s Growing, Where it’s Not, and What

the Future Holds. Available online at: https://develop.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/04/Nielsen20Global20Private20Label20Report20November202014-2.pdf, Accessed on January 22, 2022

Olsen, N.V., Menichelli, E.,

Meyer, C., Næs, T., 2011. Consumers Liking of Private Labels, An Evaluation of

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Orange Juice Cues. Appetite, Volume 56(3), pp.

770–777

Ong, J.W., Rahim, M.F.A.,

Lim, W., Nizat M.N.M., 2022. Agricultural Technology Adoption as a Journey:

Proposing the Technology Adoption Journey Map. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 13(5), pp. 1090–1096

Oracle, 2020. Private Label in APAC: Capturing Opportunity and

Protecting Your Brand, Oracle, pp.

1–14

Ostlund, L.E., 1974.

Perceived Innovation Attributes as Predictors of Innovativeness. Journal of

Consumer Research, Volume 1(2), pp. 23–29

Parthasarathy, M.,

Rittenburg, T.L., Ball, A.D., 1995. A Re-evaluation of the Product Innovation-decision

Process: The Implications for Product Management. Journal of Product &

Brand Management, Volume 4(4), pp. 35–47

Private Label Manufacturers

Association (PLMA), 2021. Private Label Manufacturers Association’s (PLMA's)

2021 Private Label Yearbook, a statistical guide to today’s store brands. Available online at:

https://plma.com/sites/default/files/files/2021-05/plma2021yearbook2.pdf, Accessed on January 23, 2022

Private Label Manufacturers

Association (PLMA), 2022. Industry News, Private Label Today. Available online at:

https://www.plmainternational.com/industry-news/private-label-today, Accessed on January 22, 2022

Richardson, P.S., Jain,

A.K., Dick, A., 1996. Household Store Brand Proneness: A Framework. Journal

of Retailing, Volume 72(2), pp. 159–185

Rogers, E.M., 1958. A

Conceptual Variable Analysis of

Technical Change. Rural Sociology, Volume 23, pp. 136–145

Rogers, E.M., 1995.

Diffusion of Innovations, In: 4th (ed.), The Free Press, New

York

Rogers, E.M., 2003.

Diffusion of Innovations, In: 5th (ed.), The Free Press, New

York

Sarkar, S., Sharma, D.,

Kalro, A.D., 2016. Private Label Brands in an Emerging Economy: an Exploratory

Study in India. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management,

Volume 44(2), pp. 203–222

Schiffman, L.G., Wisenblit,

J.L., 2015. Consumer Behavior, In: 11th (ed.), Pearson Education

Limited, England.

Sharma, V., Kedia, B.,

Yadav, V., Mishra, S.. 2020. Tapping the Potential Space-positioning of Private

Labels. Journal of Indian Business Research, Volume 12(1), pp. 43–61

Shaw, J., Giglierano, J.,

Kallis, J., 1989. Marketing Complex Technical Products: The Importance of

Intangible Attributes. Industrial Marketing Management, Volume 18 (1),

pp. 45–53

Sitorus H.M., Govindaraju,

R., Wiratmadja, I.I., Sudirman, I., 2019. Examining the Role of Usability,

Compatibility and Social Influence in Mobile Banking Adoption in Indonesia. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 10(2), pp. 351–362

Smith,

J., Johnson, A., 2022. Private label quality assessment: The role of consumer

consumption experience. Journal of

Consumer Research, 45(2), 123-145

Speed, R., 1998. Choosing

Between Line Extensions and Second Brands: The Case of the Australian and New

Zealand Wine Industries. Journal of Product and Brand Management, Volume

7(6), pp. 519–536

Sutton-Brady, C., Taylor,

T., Kamvounias, P., 2017. Private Label Brands: A Relationship Perspective. Journal

of Business and Industrial Marketing, Volume 32(8), pp. 1051–1061

Tornatzky, L.G., Klein,

K.J., 1982. Innovation Characteristics and Innovation-adoption Implementation:

A Meta-analysis of Findings. Institute of Electrical and Electronics

Engineers (IEEE) Transactions on Engineering Management, Volume EM-29(1),

pp. 28–45

Vengrauskas, P.V., 2012. The

Investigation of the Characteristics, Determining the Choice of Private Labels:

Academic and Practical Aspects. Economics and Management, Volume 17(3), pp. 1049–1059

Wu, L., Yang, W., Wu, J.,

2021. Private Label Management: A Literature Review. Journal of Business

Research, Volume 125, pp. 368–384