Mixed Balanced Truncation for Reducing the Complexity of Large-Scale Electrical and Electronic System Simulations

Corresponding email: quang.nguyenhong@tnut.edu.vn

Published at : 31 Jan 2025

Volume : IJtech

Vol 16, No 1 (2025)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v16i1.7180

Dao, H-D, Nguyen, T-T, Vu, N-K, Hoang, V-T & Nguyen, H-Q 2025, 'Mixed balanced truncation for reducing the complexity of large-scale electrical and electronic system simulations', International Journal of Technology, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 160-175

| Huy-Du Dao | Faculty of Electronics, Thai Nguyen University of Technology, Thai Nguyen 251750, Vietnam |

| Thanh-Tung Nguyen | Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Thai Nguyen University of Information and Communication Technology, Thai Nguyen 250000, Vietnam |

| Ngoc-Kien Vu | Research Development Institute of Advanced Industrial Technology (RIAT), Thai Nguyen University of Technology, Thai Nguyen 251750, Vietnam |

| Van-Ta Hoang | College of Technology and Trade, Thai Nguyen 250000, Vietnam |

| Hong-Quang Nguyen | Faculty of Mechanical, Electrical, Electronics Technology, Thai Nguyen University of Technology, Thai Nguyen 251750, Vietnam |

This study focuses on Model Order Reduction (MOR)

to optimize such systems' simulation and analysis capabilities in the context

of increasingly complex electrical and electronic systems, coupled with

computational and processing resource limitations. This paper proposes the

Mixed Balanced Truncation (MBT) algorithm, which combines the strengths of

Balanced Truncation (BT) and Positive-Real Balanced Truncation (PRBT) while

addressing their respective limitations. The MBT algorithm is developed based

on Lyapunov and Riccati equations, ensuring the stability and passivity of the

reduced-order system. The proposed method is validated through large-scale

electrical circuit systems, using RLC network models as illustrative examples.

The results demonstrate that MBT achieves effective order reduction with

minimal error while reducing computational costs. The main contributions of this

work in developing the new reduction algorithm include the introduction of a

novel definition of mixed balanced systems and theoretical advancements through

the development of theorems, lemmas, and corollaries accompanied by rigorous

mathematical proofs. This study makes significant theoretical contributions and

provides practical solutions for designing, modeling, and reducing the

complexity of electrical and electronic systems, particularly passive linear

systems in general.

Computational Efficiency; Descriptor Systems; Electrical Circuit Simulation; Mixed Balanced Truncation; Model Order Reduction

In circuit simulation, Modified Nodal Analysis (MNA) is a

widely used method for constructing mathematical models of circuit behavior (Choupanzadeh and Zadehgol, 2023; Pavan and Temes, 2023; Hao

and Shi, 2022; Günther et al., 2005). This technique represents the input-output

relationship of a circuit as a linear descriptor

system, expressed by the following equation (1).

|

|

(1) |

where

Remark

1. The system described by equation (1)

exhibits several key characteristics and requirements (these properties ensure

the system meets the demands for simulation, analysis, and the application of

model reduction algorithms):

-

The system is minimal,

ensuring no redundant states.

-

The dynamics are stable and

passive, indicating that the system does not generate energy and all

eigenvalues of the pencil matrix pair (E, A) have non-positive real

parts.

-

The initial conditions are

such that the state variables, inputs, and outputs are all zero.

-

Matrices A and E are nonsingular, with ranks equal to n, and matrices A and E-1A are stable.

-

The matrix D satisfies the condition D + DT ? 0, ensuring that the system's output matrix is

positive semi-definite.

Dimensionality Reduction (DR) or Model Order Reduction

(MOR) is a crucial technique widely applied in mathematical modeling across

various fields, including electrical and electronic systems (Benner et al.,

2021; Benner et al., 2020; Fortuna et al., 2012; Schilders et al., 2008).

The primary goal of DR and MOR is to simplify a complex, high-dimensional model

by replacing it with a lower-dimensional model while preserving the system's

essential physical properties and dynamic behavior. This simplification

significantly reduces computational complexity, enabling faster computations

required for real-time simulations. Furthermore, it reduces computational

workload and storage requirements, enhancing hardware performance and cost

efficiency, especially in resource-constrained environment.

In

large-scale circuit simulations, many model reduction algorithms are applied in

various critical applications. Among them, methods such as Krylov subspace (Freund, 2022; Freund,

2000), Rational Krylov (Ali et al., 2019), Moment Matching (Benner and Feng, 2021;

Prajapati and Prasad, 2020), Asymptotic Waveform Evaluation (Jiang and Yang,

2021), Lanczos technique (Wittig et al., 2002), Arnoldi iteration (Song et al., 2017;

Jiang and Xiao, 2015), Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (Gräßle et al.,

2020; Manthey et al., 2019), Singular Value Decomposition (Younes et al.,

2021), Principal Component Analysis (Anaparthi et al., 2005), Padé

approximation (Singh et al., 2008), Singular Perturbation (Khan et al., 2019; Huisinga and

Hofmann, 2018), Matrix Interpolation (Kassis et al., 2016; Samuel et al.,

2014), frequency weighting balance truncation (Floros et al., 2019; Rydel and

Stanis?awski, 2018), time weighting balance truncation (König and Freitag,

2023), and others stand prominent (Kumar and Ezhilarasi, 2023a; Gugercin and

Antoulas, 2004).

During

the exploration of foundational methodologies prior to developing a new model

order reduction algorithm, the research team focused particularly on two

techniques: Balanced Truncation (BT) (Axelou et al., 2023; Kumar and Ezhilarasi, 2023b; Hossain

and Trenn, 2023; Suman and Kumar, 2021; Grussler et al., 2021; Antoulas, 2005;

Mehrmann and Stykel, 2005) and Positive-Real Balanced Truncation (PRBT)

(Poort et

al., 2023; Breiten and Unger, 2022; Zulfiqar et al., 2018; Benner and Stykel, 2017;

Reis and Stykel, 2010; Reis and Stykel, 2010; Tan and He, 2007; Tan and He,

2007). These methods were prioritized due to their ability to preserve

the physical properties of the original system, specifically stability (for BT)

and passivity (for PRBT). Both BT and PRBT ensure that reduced-order models

retain these crucial physical characteristics, which are essential for circuit

simulations.

Balanced

Truncation (BT), a classical approach to MOR, was first introduced by Moore in

1981. This method has been extensively studied, refined, and applied across

various applications (Axelou et al., 2023; Kumar and Ezhilarasi, 2023b; Hossain and

Trenn, 2023; Suman and Kumar, 2021; Grussler et al., 2021; Antoulas, 2005; Mehrmann

and Stykel, 2005). BT operates by balancing the controllability and

observability Gramians of the system and then truncating states with small

singular values. This technique ensures system stability is preserved and

achieves minimal reduction error, particularly in cases of moderate-order

reduction. However, a notable limitation of BT is its inability to maintain the

passivity of the original system, which is critical in practical applications,

such as ensuring that electrical circuits do not generate energy (Breiten and Unger,

2022).

To

address the limitations of BT, the Positive-Real Balanced Truncation (PRBT)

method was developed for positive-real systems (Reis and Stykel, 2010; Tan and He, 2007).

PRBT enables model order reduction while preserving the system’s passivity, a

property that ensures the system cannot generate or amplify energy. Numerous

studies have explored improvements and applications of PRBT, highlighting its

significance in various fields (Poort et al., 2023; Breiten and Unger, 2022; Zulfiqar et

al., 2018; Benner and Stykel, 2017). Although PRBT preserves essential

physical properties such as stability and passivity, it often leads to larger

reduction errors compared to BT and involves solving more complex problems,

resulting in higher computational costs.

Several

hybrid methods have been proposed to combine the strengths of BT and PRBT while

mitigating their respective weaknesses (Salehi et al., 2022; Salehi et al., 2021a; 2021b;

2021c; Zulfiqar et al., 2020; Lindmark and Altafini, 2017; Zulfiqar et al.,

2017; Unneland et al., 2007a; 2007b; Phillips et al., 2002). These

methods often involve complex balancing techniques or employ mixed Gramians.

These methods often rely on intricate balancing techniques or the use of mixed

Gramians. However, their applicability is typically restricted to standard

linear systems, rendering them unsuitable for direct application to linear

descriptor systems, which are frequently encountered in circuit analysis

models. Furthermore, methods described in studies such as (Salehi,

Karimaghaee and Khooban, 2021a; Salehi et al., 2022; Salehi, Karimaghaee, and

Khooban, 2021b) require solving two Riccati equations, which adds

computational complexity and cost.

To

overcome these challenges, we propose a novel algorithm named Mixed Balanced

Truncation (MBT), specifically designed to reduce the order of continuous-time

descriptor systems in the circuits model. MBT leverages the advantages of both

BT and PRBT by incorporating techniques that ensure the system remains stable

and passive while minimizing computational costs and reducing errors. This

novel approach addresses the limitations of previous methods and provides a

more efficient solution for DR in practical applications.

The primary contributions of this paper include a comprehensive definition of the proposed methods, three theorems that establish the theoretical foundation, two lemmas, two corollaries, and a new algorithm. The effectiveness and applicability of the proposed MBT method are demonstrated through illustration examples and simulations. This study advances the current body of literature by providing new insights and practical solutions for model order reduction in large-scale electronic circuit simulations, representing a significant step forward in this research field. This research contributes to the theoretical understanding of MOR. It offers a practical algorithm that can be applied to improve the efficiency and performance of electronic and electrical systems. The proposed MBT method paves the way for more effective and reliable simulations, crucial for designing and analyzing modern complex systems.

Preliminaries

2.1. Balanced

Truncation (BT) for reducing model order

The Balanced Truncation (BT) algorithm is

constructed on the principle of balancing the Grammians of the system. This

involves using a non-singular transformation matrix to equalize and diagonalize

the controllability and observability of Grammians. The reduced-order model is

then obtained by eliminating the modes associated with minor Hankel singular

values, which represent low-energy modes with minimal influence on the system's

behavior. The implementation details of the BT algorithm are presented in (Axelou et al.,

2023; Kumar and Ezhilarasi, 2023b; Hossain and Trenn, 2023; Suman and Kumar,

2021; Grussler et al., 2021; Mehrmann and Stykel, 2005; Antoulas, 2005).

Theorem 1 (Antoulas,

2005). If the system described by Equation (1) is stable, then the

matrices Kc (controllability Gramian) and Ko

(observability Gramian) are symmetric and positive definite. These matrices

satisfy the following Lyapunov equations (2) and (3).

|

|

(2) |

|

|

(3) |

2.2. Positive-Real Balanced

Truncation (PRBT) for reducing model order

The Positive-Real Balanced Truncation (PRBT) algorithm extends the

principles of BT to address passive systems specifically. In this technique,

the matrices Jc (control Gramian) and Jo

(observation Gramian) are computed by solving two Riccati equations. The

implementation details of the PRBT algorithm are presented in (Poort et al.,

2023; Breiten and Unger, 2022; Zulfiqar et al., 2018; Benner and Stykel, 2017;

Reis and Stykel, 2010; Reis and Stykel, 2010; Tan and He, 2007; Tan and He,

2007).

Theorem 2 (Reis

and Stykel, 2010; Tan and He, 2007). A system described by equation (1)

exhibits passivity if and only if its transfer function G(s) is of the

positive-real type. This condition is met if there exist matrices Jc and Jo that satisfy the

following Riccati equations (4) and (5).

|

|

(4) |

|

|

(5) |

These equations ensure that the system maintains passivity while reducing

its order, effectively preserving the original system's essential

characteristics.

Reduction of

Model Order Using Mixed Balanced Truncation

The Mixed Balanced Truncation algorithm is

utilized to reduce the model order of mixed-balanced systems. Therefore, it is

first necessary to determine whether the system in question conforms to this

balanced form. A system is said to satisfy the mixed balanced property if it

fulfills the criteria specified in Definition 1.

Definition 1. A linear

descriptor system described by equation (1) satisfying Remark 1 is termed a

mixed-balanced system if it meets the following conditions (6) or (7).

|

|

(6) |

|

|

(7) |

where Kc and Jo satisfy Equations (2) and (5), and Jc and Ko satisfy Equations

(3) and (4). are the Hankel singular values of the

mixed-balanced system with

.

Remark 2. If the system described by equation (1) does

not satisfy the criteria defined in Definition 1, then it is possible to

convert this system into a mixed-balanced system using Theorem 3.

Theorem 3. Consider the system described by equation

(1) satisfying the conditions outlined in Remark 1. A non-singular

transformation always exists via a transformation matrix Tz, such as equation (8) or (9).

|

|

(8) |

|

|

(9) |

Proof of Theorem 3. By applying the

Cholesky decomposition to Kc and Jo,

followed by performing Singular Value Decomposition on the matrix , being the Cholesky factors, we then calculate Tz

and its inverse. This results in equations (10) and (11).

|

|

(10) |

|

|

(11) |

Lemma 1. For a system described by equation (1) satisfying

Remark 1, the eigenvalues of the matrices KcJo or JcKo are positive and remain invariant under

non-singular transformations facilitated by the matrix Tz.

Proof

of Lemma 1. By performing the

diagonalization of the matrix product KcJo, we derive , where ? is a diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues ?i of KcJo; Tz represents a matrix with eigenvectors of KcJo as its columns. Additionally, we have equation

(12).

|

|

(12) |

Thus, we can infer that , where

are

the Hankel singular values of the mixed-balanced system, satisfying

. Therefore, Lemma

1 is proven.

Lemma 2. For a system

described by equation (1) that meets the conditions in Remark 1, achieving a

mixed-balanced state through a non-singular transformation using the matrix Tz

is always possible, resulting in the new system matrices described by equation

(13).

|

|

(13) |

Proof of Lemma 2. When

equations (8) and (13) are substituted into equations (2) and (5), the updated

system is described by equations (14) and (15).

|

|

(14) |

|

|

(15) |

These new

equations (14) and (15) possess solutions that meet the criteria of Definition

1. Therefore, by employing the equivalent transformation with the non-singular

matrix Tz, the original system converts into the

mixed-balanced system, thereby establishing the validity of Lemma 2.

|

Algorithm 1. Reduce Model Order Using Mixed Balanced

Truncation |

|

|

Input: The dynamical system G(s) described by equation 1 satisfying the

conditions of Remark 1. Output: Reduced-order system described by the reduced matrices: |

|

|

Equivalent transformation of the original

system to a mixed-balanced system: 1. Compute Kc

and Jo from equations (2) and (5). 2. Perform Cholesky

decomposition on Kc and Jo

as equations (16) and (17). |

|

|

|

(16) |

|

|

(17) |

|

where

P and Q are invertible lower triangular matrices. |

|

|

3. Decompose the

singular values of the product |

|

|

|

(18) |

|

where

U and V are orthogonal matrices, and XB

is a diagonal matrix containing singular values. |

|

|

4. Calculate the conversion matrix Tz and

inverse according to equations (19) and (20). |

|

|

|

(19) |

|

|

(20) |

|

5. Calculate the updated system

matrices of the mixed-balanced system using the conversion equation (13). |

|

|

Reduce Model Order Using Mixed

Balanced Truncation: |

|

|

6. Choose the intended reduced

dimension r where 0 < r < n. |

|

|

7. Compute the projection

matrices as equations (26) and (27). |

|

|

|

(21) |

|

|

(22) |

|

8.

Calculate the matrices of the reduced order system as in the equations in

(23). |

|

|

|

(23) |

Remark 3. In this algorithm, we utilize the Gramians Kc and Jo. Alternatively, we can use the Gramians Jc and Ko owing to the balanced and symmetric nature of the

system.

Corollary

1. The mixed-balanced system

obtained from Algorithm 1 (from Step 1 to Step 5) retains the properties

described in Remark 1. The control matrix XBc and the observer matrix XBo of the mixed-balanced system are symmetric,

positive definite diagonal matrices, as in expression (24).

|

|

(24) |

Proof of corollary 1. To verify the stability and passivity of the

resulting mixed-balanced system, we solve the Lyapunov equation for the new

control matrix XBc and the Riccati equation for the new

observation matrix XBo, as specified in equations (25) and (26),

respectively.

|

|

(25) |

|

|

(26) |

where:

|

|

(27) |

|

|

(28) |

The

matrices XBc and XBo exhibit diagonal symmetry and positive definiteness, confirming

the conditions specified in Theorem 1 and Theorem 2. Therefore, the resulting

mixed-balanced system shows stable and passive behavior

Theorem 4: The reduced-order system obtained from

Algorithm 1 maintains the stability and passivity of the

original system (1).

Proof of

Theorem 4. Equations

(25) and (26), when represented as matrix blocks, lead to equations (29) and

(30).

|

|

(29) |

|

|

(30) |

where:

|

|

(31) |

|

|

(32) |

|

|

(33) |

Following this, the reduced-order system

satisfies the Lyapunov condition expressed in equation (34).

|

|

(34) |

and the Riccati equation (35).

|

|

(35) |

xB1 is a positive definite, symmetric, and

diagonal matrix, meeting the requirements of Remark 1, Theorem 1, and Theorem

2, so the reduced-order system obtained from Algorithm 1 preserves both the

stable and passive of the original system (1).

Corollary 2. The system was reduced using Algorithm 1, which employs the

controllability Gramian xBc and the observability Gramian xBo. Both Gramians exhibit diagonal, symmetric, and positive definite

properties, containing r Hankel singular values derived from the

original mixed-balanced system.

Proof of Corollary 2. From equations (29) to (32), it follows that what must be proven.

Theorem 5. Considering system (1) satisfying Remark 1. When applying the MBT

algorithm for order reduction, the upper bound of error is defined by condition (36).

|

|

(36) |

Proof of Theorem 5. Transforming equation (15) into equation (37)

|

|

(37) |

where is as in equation (38)

|

|

(38) |

System

(1) is a mixed-balanced system, and equations (2) and (5) are consequently

converted into equations (39) and (40).

|

|

(39) |

|

|

(40) |

These equations are two Lyapunov equations. Based on the transformations and demonstrations in the BT algorithm, the error according to the Hinf norm between the original and reduced-order systems satisfies Theorem 5.

Illustrative example

Considering

the RLC network as a model of a transmission line (Akram et

al., 2020), and selecting the number of

nodes k = 8, the order of the system is n = 15. By convention,

the state variables represent the voltage across Ci,

denotes

the current through Lj, u is the input voltage, and y

is the output current, where i ranges from 1 to 2k and j

ranges from 1 to 2k-1.

We apply

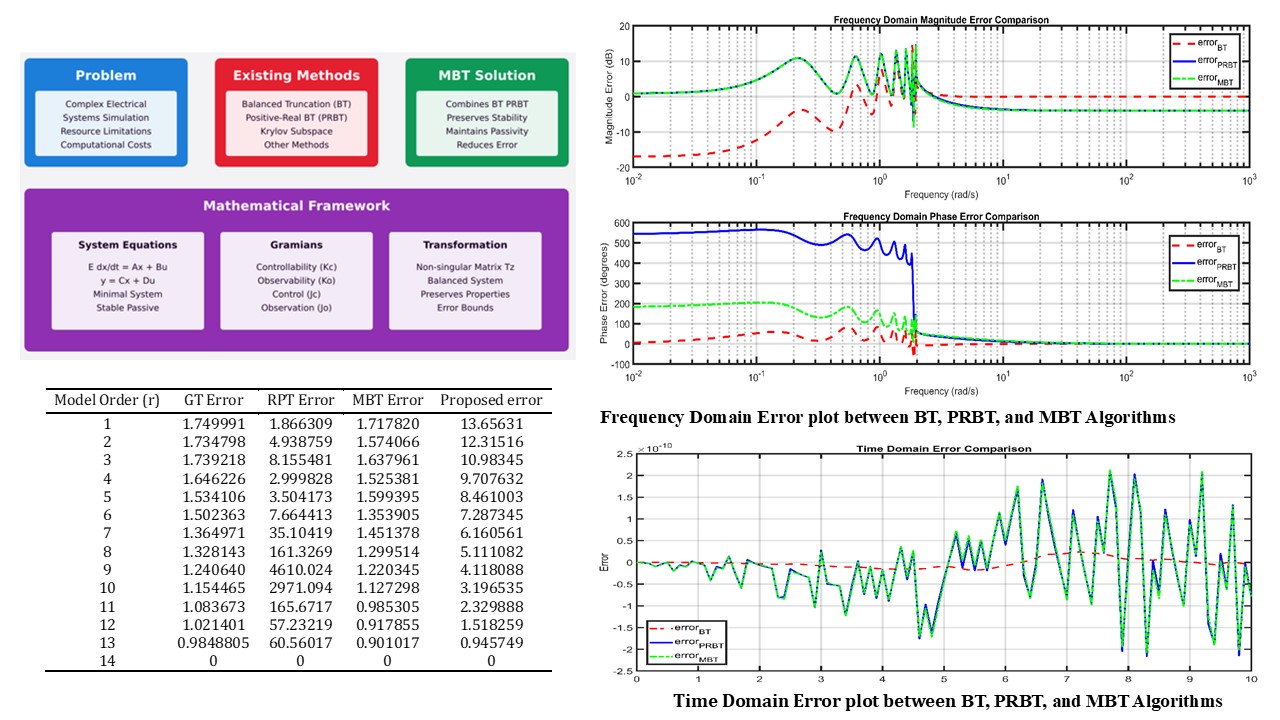

the BT, PRBT, and MBT algorithms to reduce the order of the RLC ladder network

model from r = 1 to r = n-1. Figure 1 illustrates the Absolute

Error plot using the H-infinity norm between the reduced-order and original

systems. Table 1 shows the absolute errors corresponding to each order r of the

model.

Figure 1 Absolute error plot with decreasing order of r

The plot in Figure 1 depicts the Absolute Hinf Error versus the model order r for three model reduction algorithms: BT, PRBT, and

MBT. From this result, we have the following Analysis and Observations:

-

MBT algorithm: MBT shows

stable and low error values across all model orders. This indicates that MBT is

highly reliable and maintains the accuracy of the reduction order model. The

error curve for MBT (green dash-dot line) suggests that MBT is an effective

method for model reduction.

-

BT algorithm: BT's error

curve (red dashed line) is stable and does not show significant variations,

indicating that low errors are maintained across different model orders. BT,

like MBT, proves to be a reliable method for model reduction.

-

PRBT algorithm: PRBT shows

significant fluctuations in error values across different model orders. As the

order decreases, the error of PRBT (represented by the blue solid line)

increases rapidly, indicating a lack of stability. The error values vary

considerably, depending on the chosen model order. This suggests that PRBT

might be less reliable and sensitive to the choice of r.

From Table 1, in conjunction with the numerical results, several insights

can be gleaned:

-

Both MBT and BT algorithms

show consistent and stable error reduction across all model orders. They

progressively reduce the H-infinity norm error without significant

fluctuations, making them both reliable choices for model order reduction.

-

While PRBT exhibits large

fluctuations in errors, MBT maintains a steady, demonstrating superior

stability

The Hankel singular Values (HSV)

of the transmission line model, upon transformation into a mixed-balanced

system, are detailed in Table 2. In table 2, the HSV gradually decreases as the

order r increases. This trend aligns with both theoretical expectations

and practical observations, as smaller HSV values indicate a lesser loss of

information from the original system, consequently resulting in a proportional

increase in the reduction error as the system order decreases.

By comparing Table 2 with the

error reduction upper bound formula specified by the MBT method in equation

(36), the maximum values of the estimated error are listed in the

"Proposed error" column of Table 1. When these predicted errors are

compared with the real errors shown in the "MBT error" column of

Table 1, it is clear that the formula presented in Theorem 6 is accurate.

Performing order reduction on

the RLC ladder network model to achieve a 3rd-order representation, we generate

Absolute Error in Amplitude (dB) vs. Frequency (rad/sec), Phase Error (dec) vs.

Frequency (rad/sec), and Absolute Error (Amplitude) vs. Time (second) plots for

the three methods in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively.

Table 1 Comparison of H-infinity Norm Errors between BT, PRBT, and MBT.

|

Model Order (r) |

BT Error |

PRBT Error |

MBT Error |

Proposed error |

|

1 |

1.749991 |

1.866309 |

1.717820 |

13.65631 |

|

2 |

1.734798 |

4.938759 |

1.574066 |

12.31516 |

|

3 |

1.739218 |

8.155481 |

1.637961 |

10.98345 |

|

4 |

1.646226 |

2.999828 |

1.525381 |

9.707632 |

|

5 |

1.534106 |

3.504173 |

1.599395 |

8.461003 |

|

6 |

1.502363 |

7.664413 |

1.353905 |

7.287345 |

|

7 |

1.364971 |

35.10419 |

1.451378 |

6.160561 |

|

8 |

1.328143 |

161.3269 |

1.299514 |

5.111082 |

|

9 |

1.240640 |

4610.024 |

1.220345 |

4.118088 |

|

10 |

1.154465 |

2971.094 |

1.127298 |

3.196535 |

|

11 |

1.083673 |

165.6717 |

0.985305 |

2.329888 |

|

12 |

1.021401 |

57.23219 |

0.917855 |

1.518259 |

|

13 |

0.9848805 |

60.56017 |

0.901017 |

0.945749 |

|

14 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 2 The HSV of

mixed-balanced system.

|

?i |

HSV |

?i |

HSV |

?i |

HSV |

|

1 |

1.226872736948283 |

6 |

0.586829045407931 |

11 |

0.433323477959059 |

|

2 |

0.670576895359906 |

7 |

0.563391797949794 |

12 |

0.405814550194131 |

|

3 |

0.665852832023017 |

8 |

0.524739486454494 |

13 |

0.386254508104516 |

|

4 |

0.637910984013295 |

9 |

0.496497172492625 |

14 |

0.372874846777396 |

|

5 |

0.623314517294628 |

10 |

0.460776660475757 |

15 |

0 |

From the Frequency Domain Error

plot in Figure 3, we have the Comparison (Magnitude and Phase Errors) as

follows:

- Magnitude Error:

+ error_BT (red dashed line):

The magnitude error increases from approximately -20 dB at low frequencies to 0

dB at high frequencies, suggesting that the BT algorithm exhibits higher error

compared to both PRBT and MBT.

+ error_PRBT (blue solid line): The magnitude error of PRBT is lower and

more stable than BT, but shows slight fluctuations in the mid-frequency range.

+ error_MBT` (green short dashed line): The magnitude error of MBT

closely matches PRBT at high and low frequencies, indicating that MBT performs

as well or better than PRBT and significantly better than BT.

- Phase Error:

+ error_BT: The phase error for

BT is relatively low and stable at low and mid frequencies but increases

slightly at high frequencies.

+ error_PRBT: The phase error

for PRBT is higher than BT, especially at low and mid frequencies.

+ error_MBT: The phase error for

MBT is lower than PRBT and comparable to BT at high frequencies, indicating

that MBT maintains better phase accuracy.

- Accuracy in Frequency Domain:

+ BT exhibits larger errors in

both magnitude and phase within the frequency domain, in comparison to PRBT and

MBT.

+ PRBT improves magnitude

accuracy but has higher phase errors.

+ MBT maintains the smallest

errors in both magnitude and phase, especially in the high-frequency range,

indicating better accuracy in the frequency domain.

Figure 2 Frequency

Domain Error plot between BT, PRBT, and MBT Algorithms

Figure 3 Time Domain Error plot between BT, PRBT, and MBT Algorithms

From The Time Domain Error plot

as Figure 4, we have the Comparison between BT, PRBT, and MBT algorithms as

follows:

- error_BT: The time domain

error for BT is smaller and more stable initially but tends to increase over

time.

- error_PRBT: The time domain

error for PRBT oscillates around zero, but with larger oscillations than BT.

- error_MBT: The time domain

error for MBT is very small and follows PRBT closely, indicating performance

that is equivalent to or somewhat better than PRBT but larger than BT.

Overall evaluation:

- MBT proves to be a performing

method in both the frequency and time domains, with small and stable errors.

- PRBT is also a good method,

particularly for reducing magnitude errors but has higher phase errors.

- BT performs worse compared to

PRBT and MBT, with larger errors in the frequency domain.

- Both the MBT and BT algorithms

demonstrate high reliability for model order reduction, offering stable and

consistent performance across various orders. They both achieve high accuracy

at higher orders, making them suitable for practical applications requiring

precise reduced models.

Therefore, MBT is the preferred

method for minimizing errors and maintaining the highest accuracy in model

order reduction systems. MBT proves to be a superior choice when compared to

PRBT due to its consistent, low error performance and preserved passivity,

while it matches the robustness, reliability, and stability of BT.

5.1. Contributions

to Scientific Theory of the Research Results

The research team developed a model

order reduction algorithm (Algorithm 1: Reduce Model Order Using Mixed Balanced

Truncation, MBT) to address the

limitations of two original algorithms. Specifically, MBT outperforms BT by

preserving both stability and passivity, offering lower computational costs and

reducing errors compared to PRBT.

During the development of MBT, the authors presented mathematical

arguments accompanied by proofs, including Definition 1: Mixed-balanced system

definition; Theorem 3: Existence of non-singular transformation; Lemma 1:

Eigenvalue invariance under transformation; Lemma 2: Achieving mixed-balance

via transformation; Corollary 1: Properties of the mixed-balanced system; Theorem 4: Stability

and passivity of reduced-order systems; Corollary 2: Gramian properties in

reduced systems; Theorem 5: Error bound in MBT algorithm.

The MBT reduction algorithm simplifies passive circuits with numerous

state variables, minimizing computational costs and optimizing the simulation

and analysis of high-order systems.

The algorithm and theoretical findings can be applied to the design,

development, testing, evaluation, measurement support, response prediction,

risk warning, and functional verification of high-order electrical systems

using lower-order circuit models.

The content and results of this research can serve as reference material

for learning, research, and teaching on system identification, model order

reduction, and circuit design and simulation.

The study provides knowledge and source codes to support the development

of a reduction toolbox for linear systems in MATLAB.

In resource-constrained environments:

- Complex systems with large, multi-source datasets: Obtaining

comprehensive input signals poses challenges in designing, analyzing,

surveying, evaluating, predicting, modeling, identifying, and simulating

systems. MBT focuses on the most impactful input and output signals identified

through preliminary assessments of measurable operational parameters. It does

not require a full system model. Instead, it identifies key signals, eliminates

less impactful components, and generates a reduced-order model that effectively

simulates critical responses without detailed data. This method optimizes

resource usage, ensures system performance, and preserves key feedback

properties.

- Based on statistical datasets: MBT remains crucial in reducing

complexity by focusing on the most significant state variables. This not only simplifies the system but also

accelerates signal processing and reduces computational load, ensuring enhanced

efficiency while preserving the core dynamic characteristics of the system.

5.2. Computational

Costs of the Algorithms

The BT, PRBT, and MBT algorithms

rely on the principle of Gramian balancing, followed by truncation of balanced

equivalent system matrices. The computational complexity differences stem from

solving matrix equations to determine the observability and controllability

Gramians of the original system.

Lyapunov equation complexity: . If

, the

term dominates. If

, the

term dominates. For

, the overall complexity is

.

Performance

Consideration: The complexity is primarily determined by the sizes of n

and m. In cases where m is relatively small, the computational

cost is dominated by the matrix-matrix multiplications involving A, P, and E. Solving two Lyapunov equations in BT incurs

this cost twice.

Riccati equation complexity: . If

, the complexity is dominated by

. If

, the complexity is

dominated by

. For

, the overall complexity is

. The inversion

of

and the multiplication involving B, C and D contribute significantly to the complexity

when mmm is large. This is critical for performance optimization. Solving two

Riccati equations in PRBT doubles this cost.

In MBT, determining the Gramians involves solving one Lyapunov equation

and one Riccati equation, making MBT less computationally expensive than PRBT.

5.3. Limitations

of the MBT Algorithm

While MBT achieves better

computational efficiency and lower reduction errors than PRBT, its complexity

remains higher than BT, with greater deviations from the original model.

As with most algorithms, MBT's

accuracy and processing speed depend on factors such as software data types,

matrix solver precision, hardware configuration, firmware performance,

programming language, implementation optimization, and the complexity of the

original system's data.

MBT is designed for linear

systems (1) meeting requirements in Remark 1. Systems not satisfying Remark 1

require intermediate transformations to conform to the required format.

Solving complex matrix equations

in MBT can lead to increased computational costs for systems with large

datasets, posing challenges for hardware with limited processing capabilities.

5.4. Development

Directions

Reduce algorithm complexity by

employing Newton iteration, low-rank approximations, or rational Krylov

subspace methods.

To minimize reduction-induced

errors, integrate optimization techniques (De Guzman et al., 2024; Jusuf et al.

2024; Wichapa et al. 2024; Nitnara and Tragangoon, 2023; Hendrarini et

al., 2022), with objectives such as error

minimization and preservation of system physical properties.

For nonlinear systems, preprocess

using linearization algorithms before applying MBT.

For unstable systems or those

with mixed stable/unstable components:

+ Decompose into stable and

unstable subsystems, apply MBT to the stable component, and combine the

reduced-order model with the unstable component.

+ Use partial stabilization

techniques to transform the unstable system into a stable one before applying

MBT.

In this paper, we introduced a

novel Mixed Balanced Truncation (MBT) algorithm tailored for reducing linear

time-invariant continuous-time descriptor systems, specifically within the

context of electrical and electronic circuit simulations. Our approach aimed to

amalgamate the benefits of Balanced Truncation (BT) and Positive-real balanced

truncation (PRBT) while mitigating specific drawbacks. The MBT algorithm

demonstrated superior performance in consistently maintaining low error values

across various model orders, indicating high reliability for model order

reduction with minimal loss of accuracy. Compared to BT and PRBT, MBT showed

marked improvement in error metrics, with a steady and predictable decrease in

errors, significantly outperforming PRBT, which had large fluctuations and

sensitivity to reduction order. MBT retained the essential properties of the

original system, including stability and passivity, as confirmed by theoretical

proofs and numerical simulations. Its application to an RLC ladder network

model effectively reduced computational complexity while preserving the

original system's dynamic behavior, which is valuable for resource-limited

environments. Additionally, our study contributes to the theoretical

understanding of model order reduction by providing new insights into the

transformation and balancing of descriptor systems supported by established

theorems, lemmas, and corollaries. Future work could explore further

optimizations and extensions of the MBT approach to other types of systems and

applications, thereby broadening its impact and utility within electronics and

electrical engineering.

This research was financially supported by the Program of the Ministry of Education and Training of Vietnam under grant number B2023-TNA-17.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition- Huy-Du Dao(H.-D D); Investigation, Data curation, Validation Ngoc-Kien Vu(N.-K V);Investigation, Validation Van-Ta Hoang (V.-T H); Formal analysis, Software, Resources, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Thanh-Tung Nguyen (T.-T N); Formal analysis, Supervision, Project administration Hong-Quang Nguyen (H.-Q N). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The

authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Akram, N, Alam, M, Hussain, R, Ali, A, Muhammad, S, Malik, R & Haq, AU 2020, ‘Passivity

preserving model order reduction using the reduce norm method’, Electronics,

vol. 9(6), p. 964, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9060964

Ali, HR, Kunjumuhammed, LP, Pal, BC, Adamczyk, AG

& Vershinin, K 2019, ‘Model order reduction of wind farms: Linear

approach’, IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, vol. 10(3), pp. 1194–1205, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2018.2863569

Anaparthi, KK, Chaudhuri, B, Thornhill, NF & Pal,

BC 2005, ‘Coherency identification in power systems through principal component

analysis’, IEEE transactions on

power systems, vol, 20(3), pp. 1658–1660, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2005.852092

Antoulas, AC 2005, ‘Approximation of large-scale

dynamical systems’, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, https://epubs.siam.org/doi/pdf/10.1137/1.9780898718713.bm

Axelou, O, Floros, G, Evmorfopoulos, N &

Stamoulis, G 2023, ‘Fast electromigration stress analysis using Low-Rank

Balanced Truncation for general

interconnect and power grid structures’, Integration, vol. 89, pp.

197–206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vlsi.2022.12.005

Benner, P & Feng, L 2021, ‘Model order reduction

based on moment-matching’, in Benner, P, Grivet-Talocia, S, Quarteroni, A, Rozza, G, Schilders, W

& Silveira, LM (eds),

Model order reduction: Volume 1: System-and Data-Driven Methods and Algorithms’, pp. 57–96, De Gruyter, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/52281/1/9783110498967.pdf#page=68

Benner, P & Stykel, T 2017, ‘Model order reduction

for differential-algebraic equations: a survey, in Ilchmann, A., Reis, T. (eds), Surveys in

Differential-Algebraic Equations IV, pp. 107–160, Springer, Cham, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-46618-7_3

Benner, P,

Grivet-Talocia, S, Quarteroni, A, Rozza, G, Schilders, W & Silveira

LM 2021, ‘Model Order Reduction: Volume 2: Snapshot-based methods and

algorithms’, pp. 47–96, Berlin,

Boston: Walter De Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110671490

Benner,

P, Grivet-Talocia, S, Quarteroni, A, Rozza, G, Schilders, W & Silveira, LM

2021, ‘Model order reduction: Volume 1: System-and data-driven methods and

algorithms’, p. 378, De Gruyter, https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/52281

Benner, P, Schilders, W, Grivet-Talocia, S, Quarteroni, A, Rozza, G & Silveira, LM 2020,

‘Model order reduction: Volume 2: Snapshot-Based Methods and Algorithms’,

p. 348, De Gruyter, https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/46696

Breiten, T & Unger, B 2022, ‘Passivity preserving

model reduction via spectral factorization’, Automatica, vol. 142, p.

110368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2022.110368

Choupanzadeh, R & Zadehgol, A 2023, ‘Blockwise vs.

and General MNA for MOR’, 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and

Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting (USNC-URSI), pp. 847–848,

IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/USNC-URSI52151.2023.10237944

De Guzman, CJP, Sorilla, JS, Chua, AY & Chu TSC,

2024, ‘Ultra-Wideband Implementation of Object Detection Through Multi-UAV

Navigation with Particle Swarm Optimization’, International Journal of

Technology, vol. 15(4), pp.

1026-1036, https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i4.5888

Floros, G, Evmorfonoulos, N & Stamoulis, G 2019,

‘Efficient Circuit Reduction in Limited Frequency Windows’, 2019 16th

International Conference on Synthesis, Modeling, Analysis and Simulation

Methods and Applications to Circuit Design (SMACD), pp. 129–132, IEEE, https://doi.org/10.1109/SMACD.2019.8795231

Fortuna, L, Nunnari, G & Gallo, A 2012, ‘Model

order reduction techniques with applications in electrical engineering’, Springer

Science & Business Media, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4471-3198-4

Freund, RW 2000, ‘Krylov-subspace methods for

reduced-order modeling in circuit simulation’, Journal of Computational and

Applied Mathematics, vol. 123(1–2), pp. 395–421, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0427(00)00396-4

Freund, RW 2022, ‘Electronic Circuit Simulation and

the Development of New Krylov-Subspace Methods’, in Novel Mathematics

Inspired by Industrial Challenges, pp. 29–55, Cham; Springer International

Publishing, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-96173-2_2

Gräßle, C, Hinze, M & Volkwein, S 2020, ‘Model

order reduction by proper orthogonal decomposition’, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46696/1/9783110671490.pdf#page=56

Grussler, C, Damm, T & Sepulchre, R 2021,

‘Balanced truncation of $ k $-positive systems’, IEEE Transactions on

Automatic Control, vol. 67(1), pp. 526–531, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2021.3075319

Gugercin, S & Antoulas, AC 2004, ‘A survey of

model reduction by balanced truncation and some new results’, International

Journal of Control, vol. 77(8), pp. 748–766, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207170410001713448

Günther, M., Feldmann, U & ter Maten, J 2005,

‘Modelling and discretization of circuit problems’, Handbook of numerical

analysis, 13, pp. 523–659, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1570-8659(04)13006-8

Hao, L & Shi, G 2022, ‘Realizable reduction of

multi-port RCL networks by block elimination’, IEEE Transactions on Circuits

and Systems I: Regular Papers, vol 70(1), pp. 399–412, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2022.3218548

Hendrarini, N, Asvial, M & Sari, RF 2022,

‘Wireless Sensor Networks Optimization with Localization-Based Clustering using

Game Theory Algorithm’, International Journal of Technology, vol. 13(1),

pp. 213-224, https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i1.4850

Hossain, MS & Trenn, S 2023, ‘Midpoint based

balanced truncation for switched linear systems with known switching signal’, IEEE

Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 69(1), pp. 535-542, https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.2023.3269721

Huisinga, H & Hofmann, L 2018, ‘Order reduction in

electrical power systems using singular perturbation in different coordinate

systems’, COMPEL-The international journal for computation and mathematics

in electrical and electronic engineering, vol. 37(4), pp. 1525–1534, https://doi.org/10.1108/COMPEL-08-2017-0360

Jiang, YL & Xiao, ZH 2015, ‘Arnoldi-based model

reduction for fractional order linear systems’, International Journal of

Systems Science, vol. 46(8), pp. 1411–1420, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207721.2013.822605

Jiang, YL & Yang, JM 2021, ‘Asymptotic waveform

evaluation with higher order poles’, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and

Systems I: Regular Papers, vol. 68(4), pp. 1681–1692, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2021.3052838

Jusuf, A, Jarwadi, MH, Hastungkorojati, DG, Gunawan, L,

Akbar, M, Zakaria, K, Izzaturrahman, MF & Palar, PS 2024, ‘Design

exploration and optimization of a multi-corner crash box under axial loading

via Gaussian process regression’, International Journal of Technology,

vol. 15(6), pp. 1749–1770, https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i6.7278

Kassis, MT, Kabir, M, Xiao, YQ & Khazaka, R 2016,

‘Passive reduced order macromodeling based on loewner matrix interpolation’, IEEE

Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 64(8), pp. 2423–2432,

https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2016.2586481

Khan, H, Bazaz, MA & Nahvi, SA 2019,‘Singular perturbation?based model reduction

of power electronic circuits’, IET Circuits, Devices & Systems, vol.

13(4), pp. 471–478, https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-cds.2018.5234

König, J & Freitag, MA 2023, ‘Time-Limited

Balanced Truncation for Data Assimilation Problems’, Journal of Scientific

Computing, vol. 97(2), p. 47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10915-023-02358-4

Kumar, R & Ezhilarasi, D 2023a, ‘A

state-of-the-art survey of model order reduction techniques for large-scale

coupled dynamical systems’, International Journal of Dynamics and Control,

vol. 11(2), pp. 900–916, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-022-00985-7

Kumar, R & Ezhilarasi, D 2023b, ‘A

state-of-the-art survey of model order reduction techniques for large-scale

coupled dynamical systems’, International Journal of Dynamics and Control,

vol. 11(2), pp. 900–916, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-022-00985-7

Lindmark, G & Altafini, C 2017, ‘A driver node

selection strategy for minimizing the control energy in complex networks’, IFAC-PapersOnLine,

vol. 50(1), pp. 8309–8314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2017.08.1410

Manthey, R, Knospe, A, Lange, C, Hennig, D &

Hurtado, A 2019, ‘Reduced order modeling of a natural circulation system by

proper orthogonal decomposition’, Progress in Nuclear Energy, vol. 114,

pp. 191–200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2019.03.010

Mehrmann, V & Stykel, T 2005, ‘Balanced truncation

model reduction for large-scale systems in descriptor form’, In Dimension

Reduction of Large-Scale Systems: Proceedings of a Workshop held in

Oberwolfach, Germany, October 19–25, 2003, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer

Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 83–115, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27909-1_3

Nitnara, C & Tragangoon, K 2023, ‘Simulation-Based

Optimization of Injection Molding Process Parameters for Minimizing Warpage by

ANN and GA. International Journal of Technology. Vol. 14(2), pp.

422-433, https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i2.5573

Pavan, S & Temes, GC 2023, ‘Reciprocity and

inter-reciprocity: A tutorial—Part I: Linear time-invariant networks’, IEEE

Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers, vol. 70(9), pp.

3413–3421, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2023.3276700

Phillips, J, Daniel, L & Silveira, LM 2002,

‘Guaranteed passive balancing transformations for model order reduction’, In Proceedings

of the 39th Annual Design Automation Conference, pp. 52–57, https://doi.org/10.1145/513918.513933

Poort, L, Besselink, B, Fey, RHB & van de Wouw, N

2023, ‘Passivity-preserving, balancing-based model reduction for interconnected

systems’, IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 56(2), pp. 4240–4245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2023.10.1782

Prajapati, AK & Prasad, R 2020, ‘A new model order

reduction method for the design of compensator by using moment matching

algorithm’, Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control,

vol. 42(3), pp. 472–484, https://doi.org/10.1177/0142331219874595

Reis, T & Stykel, T 2010, ‘Positive real and

bounded real balancing for model reduction of descriptor systems’, International

Journal of Control, vol. 83(1), pp. 74–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207170903100214

Rydel, M & Stanis?awski, R 2018, ‘A new frequency

weighted Fourier-based method for model order reduction’, Automatica,

vol. 88, pp. 107–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2017.11.016

Salehi, Z, Karimaghaee, P & Khooban, MH 2021a, ‘A

new passivity preserving model order reduction method: conic positive real

balanced truncation method’, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and

Cybernetics: Systems, vol. 52(5), pp. 2945–2953, https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2021.3057957

Salehi, Z, Karimaghaee, P & Khooban, MH 2021b

‘Mixed positive-bounded balanced truncation’, IEEE Transactions on Circuits

and Systems II: Express Briefs, vol. 68(7), pp. 2488–2492, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2021.3053160

Salehi, Z, Karimaghaee, P & Khooban, MH 2021c,

‘Model order reduction of positive real systems based on mixed gramian balanced

truncation with error bounds’, Circuits, Systems, and Signal Processing,

vol. 40(11), pp. 5309–5327, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-021-01734-5

Salehi, Z, Karimaghaee, P, Salehi, S & Khooban, MH

2022, ‘Phase Preserving Balanced Truncation for Order Reduction of Positive

Real Systems’, Automation, vol. 3(1), pp. 84–94, https://doi.org/10.3390/automation3010004

Samuel, ER, Knockaert, L & Dhaene, T 2014,

‘Matrix-interpolation-based parametric model order reduction for multiconductor

transmission lines with delays’, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems

II: Express Briefs, vol. 62(3), pp. 276–280, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2014.2368611

Schilders, WHA, Van der Vorst, HA & Rommes, J

2008, Model order reduction: theory, research aspects and applications.

Springer, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-540-78841-6

Singh, N, Prasad, R & Gupta, HO 2008, ‘Reduction

of power system model using balanced realization, Routh and Padé approximation

methods’, International Journal of Modelling and Simulation, vol. 28(1),

pp. 57–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/02286203.2008.11442450

Song, QY, Jiang, YL & Xiao, ZH 2017,

‘Arnoldi-based model order reduction for linear systems with inhomogeneous

initial conditions’, Journal of the Franklin Institute, vol. 354(18),

pp. 8570–8585, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfranklin.2017.10.014

Suman, SK & Kumar, A 2021, ‘Linear system of order

reduction using a modified balanced truncation method’, Circuits, Systems,

and Signal Processing, vol. 40, pp. 2741–2762, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00034-020-01596-3

Tan, S & He, L 2007, ‘Advanced model order

reduction techniques in VLSI design’, Cambridge University Press, www.cambridge.org/9780521865814

Unneland, K, Van Dooren, P & Egeland, O 2007a, ‘A

novel scheme for positive real balanced truncation’, in 2007 American

Control Conference, IEEE, pp. 947–952, http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ACC.2007.4282863

Unneland, K, Van Dooren, P & Egeland, O 2007b,

‘New schemes for positive real truncation’, Modeling, Identification and

Control, vol. 28(3), pp. 53–65, https://doi.org/10.4173/mic.2007.3.1

Wichapa, N, Pawaree, N, Nasawat, P, Chourwong, P,

Sriburum, A & Khanthirat, W 2024, ‘Process of solving multi-response

optimization problems using a novel data envelopment analysis variant-Taguchi

method’, International Journal of Technology, vol. 15(6), pp. 2038-2059,

https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i6.7134

Wittig, T, Munteanu, I, Schuhmann, R & Weiland, T

2002, ‘Two-step Lanczos algorithm for model order reduction’, IEEE

Transactions on Magnetics, vol. 38(2), pp. 673-676, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/996175/

Younes, H, Ibrahim, A, Rizk, M & Valle, M 2021,

‘Efficient FPGA implementation of approximate singular value decomposition

based on shallow neural networks’, 2021 IEEE 3rd International Conference on

Artificial Intelligence Circuits and Systems (AICAS), pp. 1–4, IEEE, http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/AICAS51828.2021.9458453

Zulfiqar, U, Imran, M, Ghafoor, A & Liaqat, M

2018, ‘Time/frequency-limited positive-real truncated balanced realizations’, IMA

Journal of mathematical control and information, vol. 37(1), pp. 64-81, https://doi.org/10.1093/imamci/dny039

Zulfiqar, U, Tariq, W, Li, L & Liaquat, M 2017, ‘A passivity-preserving frequency-weighted model order reduction technique’, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs, vol. 64, no. 11, pp. 1327-1331