Performance Comparison of Heterogeneous Catalysts based on Natural Bangka Kaolin for Biodiesel Production by Acid and Base Activation Processes

Corresponding email: eny.k@ui.ac.id

Published at : 24 Dec 2024

Volume : IJtech

Vol 15, No 6 (2024)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i6.7023

Kusrini, E., Rifqi, A., Usman, A., Wilson, L., Degirmenci, V., Aidil Adhha Abdullah, M., Sofyan, N., 2024. Performance Comparison of Heterogeneous Catalysts based on Natural Bangka Kaolin for Biodiesel Production by Acid and Base Activation Processes. International Journal of Technology. Volume 15(6), pp. 1994-2008

| Eny Kusrini | 1. Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus Baru UI, Depok 16424, Indonesia 2. Green Product and Fine Chemical Engineering Research Group, Laboratory |

| Abi Rifqi | Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus Baru UI, Depok 16424, Indonesia |

| Anwar Usman | Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Jalan Tungku Link, Gadong BE1410, Negara Brunei Darussalam |

| Lee Wilson | Department of Chemistry, University of Saskatchewan 110 Science Place, Room 156 Thorvaldson Building, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5C9, Canada |

| Volkan Degirmenci | School of Engineering, University of Warwick, Library Road, CV4 7AL, Coventry, UK |

| Mohd Aidil Adhha Abdullah | Chemical Science Program, Faculty of Science and Marine Environment, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, 21030 Kuala Nerus, Terengganu, Malaysia |

| Nofrijon Sofyan | Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus Baru UI, Depok 16424, Indonesia |

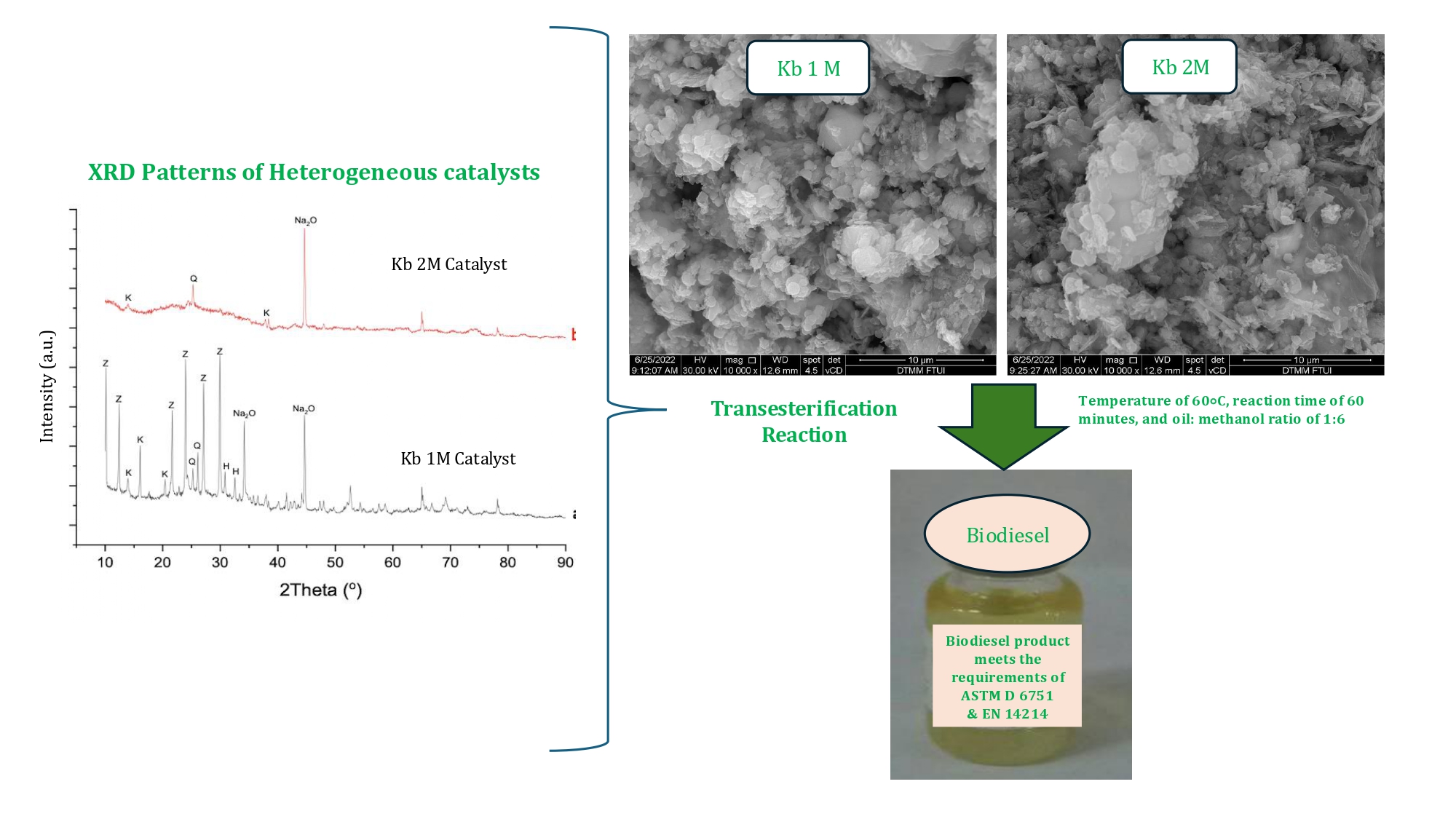

This study is aimed to evaluate e?ciency low-cost natural kaolin from Bangka island as a catalyst to produce biodiesel (fatty acid methyl ester, FAME) via the transesterification reaction using the cooking oil as a model of free fatty acids (FFA) source. Heterogeneous catalysts of the natural kaolin were prepared by an activation process using base (1-2 M NaOH) and acid (1 M HCl) solution. The base and acid activated kaolin are labelled as Kb1M, Kb2M, and Ka1M, respectively. The quality of biodiesel was analyzed according to the SNI 04-7182-2015 method, the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D 6751, and the Europäische Norm (EN) 14214, while the composition of biodiesel was determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. Among the activated kaolin, the Kb2M showed the best heterogenous catalyst performance, producing 96.3% methyl ester with a yield of 69.4%. The highest FAME conversion was achieved using the Kb1M catalyst at 79.1% with a mole ratio of cooking oil to methanol being 1:3, whereas the lowest FAME conversion, 72.0%, was obtained using the Kb2M catalyst with a mole ratio of cooking oil to methanol being 1:6. Overall, the Kb2M showed the best efficient catalyst, while the Ka1M showed the lowest catalytic performance.

Acid; Base; Biodiesel; Heterogenous Catalyst; Kaolin

Exploring new catalyst materials to meet the growing demand for renewable and fossil energy has become increasingly important for energy production. Catalysts play a crucial role in reducing activation energy and shifting the position of chemical equilibrium, allowing reactions to reach completion and produce the desired product. For the case of biodiesel production, homogeneous base catalysts such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or potassium hydroxide (KOH), and also alkoxide solutions are employed. However, homogeneous catalysts are reported to affect corrosion in the reactor, and also present challenges for catalyst recycling (Yang et al., 2017). On the other hand, heterogeneous catalysts have also been explored to reduce the cost of biodiesel production (Carmo-Jr et al., 2009).

Heterogeneous

catalysts possess different phases between reactants and products. These

catalysts have various advantages such as being environmentally compatible,

non-corrosive, easy to separate from reactants, and facile to regenerate (Guan et al., 2009). It is noted that

heterogeneous catalysts can promote the transesterification of triglycerides

for biodiesel production (Aziz et al., 2017;

Yan et al., 2010). Efforts to reduce the cost production of

biodiesel rely on the availability of abundant and cheap raw material

catalysts, sources of free fatty acid, proper reactor design, method, and type

of reaction process (transesterification or esterification).

Natural

kaolin occurs over several regions of Indonesia, such as West Kalimantan, South

Kalimantan, Bangka Belitung, Sulawesi, and Java with a total deposit of

approximately 66.21 million tons (Subari, Wenas and

Suripto, 2008). Natural Bangka kaolin has been used as an adsorbent for

the adsorptive removal of antibiotic rifampicin from an aqueous solution (Majid et al., 2023). On the other hand,

the application of Indonesian kaolin from Bangka has also been reported as an

adsorbent for adsorption of negatively charged acid blue 25 and acid 1 (Asbollah et al., 2022). Natural kaolin has

also been reported as a catalyst for transesterification reactions (Ali et al., 2018; ??ng,

Chen, and Lee, 2017). With its high

surface area, porosity, and composition, along with its low cost, the natural

kaolin highlights its potential as an effective raw catalyst material. For

instance, graphene oxide (GO) enriched natural kaolinite clay as catalyst for

biodiesel production has been reported by Syukri et

al. (2020). GO is a

single atomic layer of graphite oxide that has a high specific surface area

with a complex mixture of oxygen at the edges and basal planes (Kusrini et al., 2020a; Nasrollahzadeh et al.,

2014). GO has a Bronsted

acid side which is important for esterifying the free fatty acid (FFA) content

in oil (Atadashi et al., 2013).

It was reported that metal

oxide/GO composites increased the mechanical strength of heterogeneous

catalysts (Marso et al., 2017).

To

increase the quality and ability of natural Bangka kaolin as a heterogeneous

catalyst for biodiesel production, activation of kaolin using base and acid

treatments is needed to enhance the active sites of the natural kaolin. This

process is able to enlarge its surface area and remove impurities on the

surface of natural kaolin. Base treatment for the activation can improve

crystallinity of the natural kaolin (Belver, Bañares-Muñoz,

and Vicente, 2002). The catalyst that was activated using base treatment

showed 4,000 times faster than those found for the acid catalyst under a

similar amount of catalyst for the transesterification reaction (Fukuda, Kondo, and Noda, 2001). New catalyst

materials for energy production and/or other applications have attracted many

researchers to address the need for clean energy (Arnas,

Whulanza, and Kusrini, 2024; Whulanza & Kusrini, 2024).

Biodiesel

is an alkyl ester with other non-toxic compounds. It is a mixture of long-chain

fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) or ethyl esters (FAEEs). Biodiesel can be

produced by either the transesterification of animal fats, vegetable oils, or

used cooking oil or esterification of free fatty acids (FFAs) (Dang, Chen and Lee, 2013) in the present of

alcohol compound such as methanol (CH3OH) or ethanol (C2H5OH).

Usually, production of biodiesel through esterification and/or

transesterification reactions that are assisted by an acid or base catalyst (Maneerung et al., 2016). Biodiesel can be

obtained by a transesterification reaction, whereas the green diesel as the second

generation of diesel can be produced through hydrodeoxygenation reaction (Aisyah et al., 2023). Apart from containing esters,

vegetable oils and animal fats also contain small amounts of FFA. The presence

of FFA in the transesterification reaction with an alkali catalyst needs to be

considered. The maximum FFA content in vegetable oil when using a base catalyst

is approximately 3%, if it exceeds this level the reaction cannot occur, as reported

by Atadashi et al. (2013). This is because free fatty acids will

react with an alkali catalyst to form soap. Thus, before the

transesterification reaction was carried out, the oil must be first pretreated

to reduce the FFA content. After the transesterification reaction was complete,

two products will be obtained, namely biodiesel (methyl ester) and glycerol.

Although

sources of biodiesel can be vegetable oils such as palm oil, coconut oil, corn

oil, soybean oil, sunflower seed oil, and rapeseed oil, non-edible oils such as

jatropha curcas, pongamina pinnata, sea mango, palanga, and/or tallow oil are

more preferred (Leung, Wu and Leung, 2010). Many countries use vegetable oils as

the main ingredient for making biodiesel because the properties of the

biodiesel produced are close to those of diesel fuel (Gui et al., 2008). Biodiesel has

advantages compared to diesel fuel from petroleum. The advantages of biodiesel

are an environmentally friendly fuel because it produces much better emissions

(free sulfur and smoke number), and higher cetane number (>50). Thus, the

combustion efficiency of biodiesel is better than that of crude oil, displays

lubricating properties for engine pistons, and improves vehicle life, safe

storage, and transport, including its non-toxic and biodegradable properties (Balat and Balat, 2010). Biodiesel is an ideal

fuel for the transportation industry because it can be used in various diesel

engines, including agricultural machines.

Thus, to

observe the potential of Bangka kaolin as a heterogeneous catalyst for

biodiesel production, this natural kaolin was activated using a base solution (1–2

M NaOH) and in acid (1 M HCl) media. Both heterogeneous catalysts were

evaluated and tested for biodiesel production, where cooking oil was used as a

source of free fatty acid (FFA) for biodiesel production. Kaolin was chosen as

the model clay for the development of the e?cacious heterogeneous catalyst in

production of biodiesel through the catalyzed transesterification reaction.

2.1.

Materials

Natural

kaolin was originated from Bangka, Belitung Island, Indonesia. Palm cooking oil

is a commercial product containing FFA <2%. NaOH and HCl were purchased from

Merck (Germany). All the chemicals were used without any further purification.

2.1.1. Pretreatment of natural kaolin

50 g of Bangka

natural kaolin (150 mesh) was mixed with 400 mL of distilled water and stirred

using a magnetic stirrer until the mixture became homogeneous. The natural

kaolin was then separated from this mixture using the centrifugation technique.

The clean natural kaolin was dried in an oven at 105°C for 2 h. Furthermore, a

dried natural kaolin was calcined at 500°C for 6 h to form a metakaolin. Then,

a metakaolin was used to produce a heterogeneous catalyst in subsection 2.3.

2.2. Activated heterogeneous catalysts using base and acid

treatments

Each sample of

metakaolin (3.7 g) was mixed with at 1 M or 2 M NaOH solution, along with

magnetic stirring at 500 rpm for 6 h at room temperature. Then, the base

metakaolin obtained by using 1 M and 2 M NaOH in the respective order were

separated from the NaOH solution using a centrifugation process for 10 minutes

at a speed of 2500 rpm. The solid base metakaolin was washed using distilled

water, and it was dried in an oven at 105°C for 2 h. Each base metakaolin

product was calcined in the furnace at 500°C for 6 h. Finally, both

heterogeneous catalysts were produced and named as follows: base-activated

kaolin using 1 M NaOH (Kb1M) and base-activated kaolin 2 M NaOH (Kb2M). A

similar procedure was used to produce acid-activated kaolin using 1M HCl solution,

which was named as acid-activated kaolin 1 M (Ka1M).

2.3. Performance test of heterogeneous catalysts for

biodiesel production

The palm cooking oil

was used as a model source of oil. This oil was heated at 65°C. A mixture of

methanol and catalyst with a ratio of 1:3 was added into the heated cooking oil

and stirred using magnetic stirring at 500 rpm and 60°C for 60 minutes. The

ratio of catalyst to cooking oil is 3 wt.%. Then, the mixture was put in the

separated funnel and kept for 6 h until 2 layers formed, where the biodiesel

(fatty acid methyl ester, FAME) product was obtained. FAME was washed using a

warm water until the color of the water was clean. A product of biodiesel was

heated at 110°C to remove the remaining water. Finally, the biodiesel product

was kept for further characterization according to the SNI 04-7182-2015 method.

2.4. Characterizations

where L is crystallite size, is

wavelength of diffraction light (0.15406 nm),

full width at half maximum

(FWHM) in radians, K is constant (0.89), and

is diffraction angle.

The results of the

transesterification reaction, namely FAME were analyzed using GCMS. The quality of FAME was

determined using the SNI quality standards 04-7182-2015 method, the American

Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D 6751, and the Europaische Norm (EN)

14214, including density, viscosity, and FAME %. The FAME yield was calculated

using an equation that was reported by Soetaredjo et

al. (2011). FAME % yield and % conversion based on the GC-MS

analysis were also calculated using Equations 2 and 3;

3.1. Preparation of kaolin to metakaolin

Pre-treatment of kaolin

aims to reduce impurities and eliminate the water content present in natural

kaolin. No color change was observed in the kaolin before and after calcination

at 500°C. At a calcination temperature of 500°C, the bond between the hydroxyl groups

attached to the octahedral alumina on the kaolin surface weakens and breaks

which is called pre-dehydroxylation. A dehydroxylation reaction occurred, where

the hydroxyl group bonds in natural kaolin absorb energy which then decomposes.

Removal of nearly all hydroxyl groups from natural kaolin causes the crystal

structure of kaolin to break down, which then becomes amorphous. This amorphous

phase of kaolin is called a metakaolin. A comparison of the color of kaolin

(150 mesh), heated in an oven and after calcination at 500°C is shown in Figure 1A-C.

Figure 1 Preparation of (A) natural kaolin 150 mesh, (B) kaolin after oven

heating, and (C) kaolin after calcination (metakaolin)

3.2. The physical properties of activated

Kaolin

Comparison of the physical properties of activated kaolin using 1M or

2M NaOH, the kaolin was separated from the NaOH solution after washing with

distilled water. The dried kaolin and the calcined kaolin (metakaolin) are

shown in Figure 2A-E.

All

heterogeneous catalysts were produced, namely Kb1M, Kb2M, and Ka1M. The

addition of NaOH and HCl aims to dissolve silica and alumina from natural

kaolin. NaOH acts as a metallizer and a base agent because the kaolin structure

forms an excess negative charge on the aluminum ion in order to support cations

that are needed outside the framework to neutralize its surface charge. The

addition of NaOH as a mineralizer in the synthesis of kaolin catalysts due to

the capacity of water as a solvent at high temperatures is often unable to

dissolve substances in the crystallization process. The activation process can

enlarge the pore size and open the pores of natural kaolin. On the other hand,

the calcination process at the activation stage aims to ensure the formation of

crystals on the kaolin surface. In general, the reaction mechanisms are

illustrated in Equations (4) and (5);

Figure 2 Comparison of the physical properties of (A) activated kaolin using NaOH

(1M and 2M), (B) kaolin that was separated from the NaOH solution, (C) washing

of kaolin using aquadest, (D) dried kaolin, and (E) calcined kaolin

(metakaolin)

3.3. FTIR spectral characterization

FTIR characterizations were

only carried out for 2 types of heterogeneous catalysts, namely Kb1M and Kb2M.

The FTIR spectra of catalysts Kb1M and Kb2M are shown in Figure 3(A-B). Both FTIR spectra are not similar

since the intensity of the absorption peaks show variability, as noted for the

weak band at 3648 cm-1, strong bands at 1032; 1012 cm-1

for Kb1M, and 3366 cm-1, 1051; 1032 cm-1 for Kb2M. The

Kb1M catalyst has an absorption peak at 704 cm-1, showing the

asymmetric stretching of Si-O-Si and Al-O-Al. The absorption bands at 1012 cm-1

and 1032 cm-1 indicate the presence of O-Si-O and O-Al-O asymmetric

stretching vibrations of the aluminosilicate framework. One of the

characteristics of zeolite A is having double rings which is revealed by the

absorption for the IR band at ??550 cm-1. The peaks at 1456 cm-1

and 1507 cm-1 relate to the bending vibration of the Si-O-Si group.

The band at 3648 cm-1 was observed for Kb1M, while the peak at 3366

cm-1 was observed for KB2M. This peak is assigned for the vibration

of the hydroxyl (O-H) group. The IR band at 2972 cm-1 shows the

Al-O-Na vibration. An IR band at 688 cm-1 shows the symmetrical Si-O

and Al-O vibrations for the Kb2M catalyst.

For

comparison purposes, the FTIR spectra of Kb1M and Kb2M are quite different than

the FTIR spectra of zeolite A, as reported by Kusrini

et al. (2024a; 2024b). Generally, the vibrational bands of

zeolite A appeared at 2175, 1989, and 879 cm-1, where the absorption

peak at 879 cm-1 was attributed to the internal vibrations of Si-O

and Al-O bonds and the asymmetric stretching within the tetrahedral zeolite

structure (Kusrini et al., 2024a; Kusrini et

al., 2024b).

Figure 3 FTIR spectra of (A) Kb1M and (B) Kb2M catalyst materials

3.4. XRD characterization

XRD patterns of

heterogeneous catalysts (Kb1M and Kb2M) are shown in Figure 4(A-B). Based on

Figure 4(A), the XRD results of the Kb1M catalyst showed the appearance of XRD

signatures at values of 10.15°; 12.44°; 21.65°; 23.98°; 27.1°; and 29.94°, which provide support of the formation of zeolite A. By comparison,

the XRD result in Figure 4(B) for Kb2M showed the appearance of a band at

25.28°, which indicates that quartz was still present. The dominant crystal

structure is kaolin, while the Q peak in the form of quartz (SiO2)

is a crystalline phase only slightly observed in the XRD pattern, where the

peak of SiO2 occurs at

26.61°. The formation of zeolite A is

not supported by the Kb2M catalyst. Based on a calculation

using the Debye-Scherrer equation (Equation 1), we obtained the crystallite sizes of the Kb1M and Kb2M catalysts. The crystallite size of Kb1M is larger (41.73 nm) compared to Kb2M (23.64 nm), as shown in Table 1. This size is smaller than those found by Kusrini et al. (2024b) with crystallite

size of 49.22 nm and crystallinity of NaA

is 99.73%.

Figure 4 XRD patterns of the heterogeneous catalyst materials:

(A) Kb1M, and (B) Kb2M, where K (kaolinite), Q (quart), and Z (zeolite A) are

indicated

Table 1 Comparison of heterogeneous catalyst crystal size using

Debye-Scherrer Equation

3.5. SEM-EDX studies

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterization

was carried out to determine the morphology and surface structure of the

catalysts. Based on Figure 5, the morphology of the Kb1M catalyst showed

uniform cube-shaped crystals for zeolite A. In this study, the aim to obtain e?cient catalysts from lost-cost natural

kaolin, not to synthesize purposely the zeolites. However, the kaolin-derived

catalysts possessed the characteristics of Na-zeolite A (NaA). This SEM

image showed that zeolite A particles are cubic in shape with sharp edges. It is similar

reported by Kusrini et al. (2024b), where the NaA

has the morphology of a perfect cube with sharp cube edges, while zeolite A or

Linde Type-A (LTA) is the result of the synthesis of alumina silicate minerals

which have a cube morphology with blunter cube ends.

Figure 5 SEM images

of the catalyst materials: (A) Kb1M and (B) Kb2M with 20,000×

magnification

From this

study, the Kb1M catalyst has sharp edges with a cubic shape that resembles the

NaA material reported by Kusrini et al. (2024a; 2024b). It is also similar to the

results reported by Farghali, Abo-Aly, and Salaheldin (2021) where zeolite A has a uniform cube

shape with an average particle diameter of 1 The SEM results for the Kb2M catalyst showed a typical morphology of

kaolinite in the form of a group of layered hexagonal sheets with heterogeneous

sizes and a few typical zeolite cube crystals. This morphology can be

attributed to an incomplete calcination process or imperfect grinding of the

hexagonal sheets into cube crystals, and may also be influenced by the

concentration of NaOH.

The EDX spectra of both heterogeneous catalysts of Kb1M and Kb2M showed

the elements present on the sample surface, including C, O, Na, Al, and Si (Table 2). The presence of C in Kb2M may be due to

impurities and/or other precursors. It is similar observed with NaA that

reported by Kusrini et al. (2024a). The

formation of heterogeneous catalysts using pre-treatment, calcination, and

activation stages using NaOH solution ranged from 1–2 M, which gave rise to the

formation of zeolite A. With the addition of NaOH, the Si/Al ratio of the Kb1M

and Kb2M catalysts varied from 1.154 to 1.246 (see Table 2). The zeolite A

morphology and the Si/Al ratio are comparable with results reported by Kusrini et al. (2020b). Na-zeolite A (NaA) reported

by Kusrini et al. (2024b), the Si/Al

rasio is 1.007. However, according Kusrini et

al. (2024a), the Si/Al ratio is 2.469. The Si/Al ratio of zeolite A

can differ due to the NaOH concentration, pre-treatment, size of kaolin, and

the sequence of synthetic steps that follow the hydrothermal and calcination

techniques.

Table 2 Compariosn of EDX compositional characterization of the heterogeneous catalysts

(Kb1M and Kb2M) and NaA

|

Material |

Element (At %) |

Ratio |

Reference | ||||

|

|

C |

O |

Na |

Al |

Si |

Si/Al |

|

|

Kb1M |

- |

46.89 |

11.96 |

18.32 |

22.83 |

1.246 |

|

|

Kb2M |

06.53 |

48.21 |

10.87 |

15.97 |

18.43 |

1.154 |

|

|

NaA |

- |

39.49 |

9.21 |

13.46 |

14.76 |

1.097 |

Kusrini et al.

(2020b) |

|

NaA |

3.147 |

40.217 |

11.303 |

12.96 |

32.003 |

2.469 |

Kusrini et al.

(2024a) |

|

NaA |

- |

39.49 |

9.21 |

13.46 |

13.55 |

1.007 |

Kusrini et al.

(2024b) |

3.6. Production of

Biodiesel via a Transesterification Reaction

The

Kb1M, Kb2M, and Ka1M materials as heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel

production using transesterification reaction were studied in detail. The acid number of cooking oil is

0.56 mg KOH/g. This value shows that the cooking oil as a model can be used

directly to produce biodiesel via the transesterification reaction. If the

value of acid numbers is high that can indicate high FFA levels, which can

inhibit the biodiesel formation process. This can also lead to a saponification

reaction. The variation of mole ratio of cooking oil:methanol used in the

transesterification reaction are 1:3 and 1:6 to obtain the best ratio of

cooking oil:methanol for biodiesel production. Furthermore, the palm cooking

oil was heated at a temperature of 65°C to remove the water content contained

in the oil. High water content can cause the reaction to undergo

saponification, which causes a reduction of the methyl ester yield and

challenges for separating glycerol from the methyl ester, including an increase

in viscosity and emulsion formation. The catalyst content of 3 wt.% was used

for the biodiesel production.

Initially, the process for the

production of biodiesel was started by mixing heated cooking oil, methanol, and

respective catalysts Kb1M or Kb2M in a reactor at a temperature of 60°C during

a reaction time of 60 minutes. After the transesterification reaction, the

process was complete, and the mixture was transferred to a separatory funnel to

separate the formed phases. After separation from the separatory funnel, the

biodiesel product was washed with warm water until the color of the water was

no longer cloudy. Washing with the warm water prevents the precipitation of

saturated methyl esters and the formation of emulsions. It is noted that the heterogeneous catalyst exhibits better reusability, multiple

cycles, and easier separation compared to the homogenous catalyst. The

major causes of catalyst deactivation can be occurred if the leaching of active

sites, clogging of pore spaces of catalyst, the multiple cycles, and thus the

performance of heterogeneous catalyst, were reduced. This condition is comparable

with the biodiesel production that reported by Dang,

Chen and Lee (2013). The palm

oil produced the yield approximately 95% with the operation condition for

biodiesel production after 2 h of reaction at 63°C (Dang, Chen and Lee, 2013). Almost 90% of triglycerides in palm oil was converted

to biodiesel after 6 h of reaction at 50°C.

The temperature reaction in this study is similar to biodiesel

production from palm fatty acid distillate (PFAD) using ZrO2/bagasse

fly ash catalyst with FFA esterification conversion of 90.6% as reported by Rahma and Hidayat (2023). They reported that the

reaction temperature of 60°C, ratio of methanol to palm fatty acid

distillate of 10:1, catalyst loading of 10 wt.% of PFAD, and reaction time of 2

h.

3.7. GC-MS

characterization

GC-MS

analysis was carried out to determine the composition of methyl esters

contained in a biodiesel product. The identified methyl esters were compared

with standard references, based on the respective retention time data which was

confirmed by mass spectrometry from the GCMS results with a cooking

oil:methanol mole ratio (1:3) and (1:6) (see Table 3). Kb1M catalyst produced

35.1% area of methyl ester at a mole ratio (1:3) and 86.5% at a mole ratio

(1:6). As shown in Table 3, the Kb2M catalyst can produce 96.3% of the area of

methyl ester with a mole ratio of cooking oil:methanol (1:6). Meanwhile, the

Ka1M catalyst did not produce any area (0% based on GCMS results) for the

methyl ester. This indicates that the Ka1M material cannot be used as a

catalyst for biodiesel production via transesterification reaction since the

acid cannot change FFA to FAME. Kaolin as catalysts in biodiesel production via

transesterification reaction of vegetable oils in excess of methanol has been also

reported by Dang,

Chen, and Lee (2013). However, the conversion efficiencies were

approximately 2.2 and 2.6%, respectively, for soybean oil and palm oil after 40

h of transesterification reaction (Dang, Chen, and Lee (2013).

As shown in Table 3, it can be seen that the

highest FAME yield was 69.4% using Kb2M at a ratio of cooking oil: methanol

(1:6). The best and optimum use of cooking oil:methanol mole ratio is at 1:6

ratio because it produces a large FAME yield. When compared to a 1:3 ratio, the

FAME yield was 63.2% using Kb1M at a ratio of cooking oil:methanol (1:6) and

27.8% at a ratio of cooking oil:methanol (1:3). It is also comparable procedure

with the transesterification reaction of blended oils at 60°C for 1 h, and the

mole ratios of oil:methanol varied 1:3, 1:6, 1:9, 1:12, and 1:15 that reported

by Wahyono et al. (2022). The oil:

methanol mole ratios of 1:6 produced the best yield of 92.99% with the

conversion of 99.58% mass according to the GCMS results (Wahyono et al., 2022). Additionally, metakaolin was

activated using a 1 M HCl solution. This process does not result in the

production of FAME since the acid catalyst does not generate any fatty acids.

Table 3 Comparison of yield and conversion of FAME with a variable mole ratio of

oil: methanol 1:6 and 1:3.

|

Type of catalyst |

The mole ratio cooking oil:

methanol (1:6) | |||

|

|

Yield

FAME (%) |

Weight

(g) |

Conversion (%) |

Weight

(g) |

|

Kb1M |

63.16 |

48.93 |

73.03 |

48.93 |

|

Kb2M |

69.39 |

21.61 |

72.03 |

21.61 |

|

Ka1M |

0 |

|

75.89 |

|

|

|

The mole ratio cooking oil:

methanol (1:3) | |||

|

|

Yield

FAME (%) |

Weight

(g) |

Conversion (%) |

Weight

(g) |

|

Kb1M |

27.80 |

53 |

79.10 |

53 |

The

highest FAME conversion rate (79.1%) was achieved using Kb1M with a mole ratio

of 1:3. On the other hand, the lowest FAME conversion rate was 72.0% using Kb2M

with a mole ratio of 1:6. However, it is important to note that this conversion

value alone does not determine the quality of the resulting FAME. This

conclusion is supported by the GCMS results. It is also worth mentioning that

transesterification reactions do not always yield biodiesel. ??ng, Chen and Lee (2017) reported the conversion

yield of triolein to biodiesel increased up to 94.3% when the aging for time preparation

of the zeolite Linde Type A (LTA)-kaolin catalysts were extended from 6 to 48 hours.

The excess methanol for production of biodiesel using triglycerides as source is

one of optimum condition chosen.

The

physical properties of biodiesel products were analyzed, according to the

Indonesian National Standard (SNI) number 7182:2015 method for biodiesel. Table

4 shows the density and viscosity of the synthetic biodiesel that is

accompanied by standard data from SNI No. 7182:2015.

Table 4 Comparison of the physical

properties of biodiesel using an oil: methanol ratio of 1:6

|

Parameter |

Catalyst Type |

SNI 04-7182-2015 |

ASTM D 6751 |

EN 14214 | |

|

Kb1M |

Kb2M |

|

| ||

|

Density (kg/m3) |

895.2 |

898.1 |

850-890 |

900 |

860–900 |

|

Kinematic Viscosity

at 40°C mm2/s (CST) |

31.85 |

38.65 |

2.3-6.0 |

5.0 |

3.50–5.0 |

|

Acid Value (mg

KOH/g) (max) |

2.4 |

2.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.50 |

|

Total glycerol (%

mass) (max) |

Not determined |

Not determined |

0.24 |

0.24 |

0.25 |

|

Methyl ester (%

mass, min) |

86. |

96.3 |

96.5 |

|

96.5 |

The cooking oil employed has a density of 899 kg/m3 and a

viscosity of 48.62 cSt. A minor decrease in density occurs that was caused by

the reaction of triglycerides in cooking oil with methanol. Thus, the

triglycerides were converted into methyl esters. The characteristics of biodiesel products from

this study were compared with the biodiesel quality standards of the American

Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D 6751, Europäische Norm (EN)

14214 (European Committee for Standardization,

2002), and SNI 7182 (The National

Standardization Agency of Indonesia, 2015). The viscosity of the

biodiesel produced from the synthesis is relatively high and falls outside the

acceptable range according to the SNI standard. However, the biodiesel products

meet the requirements of ASTM D 6751 and EN 14214, primarily due to their acceptable

density properties and percentage of methyl ester by mass. The high viscosity

value is caused by the incomplete transesterification reaction and the large

number of FFA with long carbon chains in the biodiesel product. The high

mechanical viscosity of biodiesel probably occurs due to incomplete glycerol

separation.

Comparison of the biodiesel

produced by the heterogeneous catalysts (Kb1M and Kb2M) are shown in Figure 6.

The Kb2M catalyst showed the highest catalytic performance, which produced a

methyl ester area of 96.3% with a yield of 69.4%.

On the other hand, the oxide

lanthanides composites such as CaO/La2O3, MgO/La2O3,

and CaO/CeO2 were also reported and used as heterogeneous catalysts

for biodiesel production. In this sense,

the lanthanides as critical minerals and have many applications for petroleum

productions, energy, catalyst,

and antiamoebic activity (Kusrini et al.,

2024c).

These oxides can increase the catalytic activity and stability, as they have much better

resistance towards FFA in biodiesel reactions (Santoro et al., 2016). Additionally, the clay was

also reported as a catalyst which can improve for distributing lanthanides into

the clay. It can be useful for increasing the number of active sites on a

catalyst, thus the contact between the reactants and the catalyst will be

greater and product formation will be faster. Biodiesel is one of renewable

energy option that can be further produced to fulfil the need of energy in

Indonesia. This fuel is economically viable and environmentally friendly (Ebrahimi et al., 2024). These factors were

attributed to the high energy density, biodegradability, a reliable supply

chain, and non-toxicity. The main component of biodiesel is methyl esters that

can derived from various biomass sources including non-edible oil, edible, waste,

plant oils and/or and discarded cooking oils. This innovation can be more

promising as Indonesia has enormous abundant resources for biodiesel production

to reach the Golden Indonesian in 2045 and to reduce the energy crisis. This

will become more pronounced by

utilizing

different kinds of heterogeneous catalysts found locally as

resources to provide a renewable

energy including biodiesel, jet fuel and/or

biogasoline as an alternative

energy now and in the future.

Figure 6 Comparison of biodiesel produced by

heterogeneous catalysts of Kb1M and Kb2M. Operation condition at 60°C, reaction

time of 60 minutes, and oil:methanol ratio of 1:6

In this study, application of low-cost natural kaolin as a catalyst to produce biodiesel (fatty acid methyl ester, FAME) via the transesterification reaction using the cooking oil as a model of free fatty acids (FFA) has been evaluated. Natural kaolin was calcined and activated using base (NaOH) and acid (HCl) additives in solution to produce heterogeneous catalysts that were used for biodiesel production. Unexpectedly, the activation leads the formation of zeolite A, so that the kaolin-derived catalysts possessed the characteristics of zeolite NaA. The Kb1M catalyst has NaA morphology, whereas the Kb2M catalyst shows partial morphology of zeolite A that still maintains the hexagonal sheets that are typical of kaolinite. The quality of biodiesel products does not fulfil the standard SNI 04-7182-2015, except for the methyl ester area, according to the results of this study. However, the biodiesel products are acceptable for ASTM D 6751 and EN 14214 mainly for the density properties and % mass of methyl ester. In future, the Kb2M catalyst can be optimized further to obtain the best catalyst and meet the SNI 04-7182-2015 standards across all parameters. On the other hand, further investigation can be continued to obtain the biodiesel and having favorable properties for ASTM D 6751 and EN 14214, thus it could be leveraged in industrial biodiesel production. The Kb2M catalyst has the highest catalytic performance, which produced a methyl ester area of 96.3% with a yield of 69.4%. Future research would be exploring alternative activation methods and scaling up production of biodiesel using kaolin, graphene, lanthanides and/or their composites as catalysts for commercial applications.

The authors thank to International Indexed Publication (Publikasi Terindeks Internasional, PUTI) Q1 grant 2023—2024, NKB-508/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2023 from Universitas Indonesia (UI) for their financial support.

Aisyah, A.N., Ni’maturrohmah, D., Putra,

R., Ichsan, S., Kadja, G.T.M, Lestari, W.W., 2023. Nickel Supported on

MIL-96(Al) as an Efficient Catalyst for Biodiesel and Green Diesel Production

from Crude Palm Oil. International Journal of Technology, Volume 14(2), pp. 276–289. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i2.5064

Ali, B., Yusup, S., Quitain, A.T., Alnarabiji, M.S., Kamil, R.N.T.,

Kida, T., 2018. Synthesis of Novel Graphene Oxide/bentonite bi-functional

Heterogeneous Catalyst for One-pot Esterification and Transesterification

Reactions. Energy Conversion and Management, Volume 171, pp.1801–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.06.082

Arnas, Whulanza, Y., Kusrini, E., 2024. Unveiling

Innovations Across Multidisciplinary Horizons. International Journal of

Technology. Volume 15(2), pp. 240–246.

https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i2.6933

Asbollah,

M.A., Sahid, M.S.M., Padmosoedarso, K.M., Mahadi A.H., Kusrini E., Hobley, J.,

Usman A., 2022. Individual and Competitive Adsorption of Negatively Charged

Acid Blue 25 and Acid Red 1 onto Raw Indonesian Kaolin Clay. Arabian

Journal for Science and Engineering, Volume 47(5), pp.

6617–6630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-06498-3

Atadashi,

I.M., Aroua, M.K., Aziz, A.A., Sulaiman, N.M.N., 2013. The Effects of Catalysts

in Biodiesel Production: A Review. Journal of Industrial and

Engineering Chemistry, Volume 19(1), pp. 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2012.07.009

Aziz,

M.A.A., Puad, K., Triwahyono, S., Jalil, A.A., Khayoon, M.S., Atabani, A.E.,

Ramli, Z., Majid, Z.A., Prasetyoko, D., Hartanto, D., 2017. Transesterification

of Croton Megalocarpus Oil to Biodiesel Over WO3 Supported on Silica

Mesoporous-macroparticles Catalyst. Chemical Engineering Journal,

Volume 316, pp. 882–892.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.02.049

Balat,

M., Balat, H., 2010. Progress in Biodiesel Processing. Applied Energy,

Volume 87(6), pp.1815–1835.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.01.012

Belver,

C., Bañares-Muñoz, M.A., Vicente, M., 2002. Chemical Activation of a Kaolinite

under Acid and Base Conditions. Chemistry of Materials, Volume

14(5), pp. 2033–2043.

https://doi.org/10.1021/cm0111736

Carmo-Jr,

A.C., de Souza, L.K., da Costa, C.E., Longo, E., Zamian, J.R., da Rocha Filho,

G.N., 2009. Production of Biodiesel by Esterification of Palmitic Acid Over

Mesoporous Aluminosilicate Al-MCM-41. Fuel, Volume 88(3), pp. 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2008.10.007

Dang,

T.H., Chen, B.-H., Lee, D.-J., 2017. Optimization of Biodiesel Production from

Transesterification of Triolein Using Zeolite LTA Catalysts Synthesized from

Kaolin Clay. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, Volume

79, pp. 14–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2017.03.009

Dang,

T.H., Chen, B.-H., Lee, D.-J., 2013. . Application of Kaolin-Based Catalysts in

Biodiesel Production via Transesterification of Vegetable Oils in Excess

Methanol. Bioresource Technology, Volume 145, pp. 175–181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.024

Ebrahimi,

A., Haghighi, M., Ghasemi, I., Bekhradinassab, E., 2024. Design of Highly

Recoverable Clay-Foundation Composite of Plasma-Treated Co3O4/Kaolin to Produce

Biodiesel from Low-Cost Oil. Fuel, Volume 366, p. 131267.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131267

European

Committee for Standardization (CEN), 2002. Europäische Norm (EN) 14214:2002.

Automotive Fuels - Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) for Diesel Engines

Requirements and Test Methods. Brussels, Belgium

Farghali,

M.A., Abo-Aly, M.M., Salaheldin, T.A., 2021. Modified Mesoporous

Zeolite-A/reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite for Dual Removal of Methylene

Blue and Pb2+ ions from Wastewater. Inorganic Chemistry

Communications, Volume 126, p. 108487.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108487

Fukuda, H., Kondo, A., Noda, H., 2001. Biodiesel Fuel Production by

Transesterification of Oils. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering,

Volume 92(5), pp. 405–416.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80288-7

Guan,

J., Yang, G., Zhou, D., Zhang, W., Liu, X., Han, X., Bao, X., 2009. The

Formation Mechanism of Mo-methylidene Species Over Mo/HBeta Catalysts for

Heterogeneous Olefin Metathesis: A Density Functional Theory Study. Journal

of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical, Volume 300(1-2), pp. 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2008.10.044

Gui, M.M., Lee, K.T., Bhatia, S., 2008. Feasibility of

Edible Oil vs. Non-edible Oil vs. Waste Edible Oil as Biodiesel

Feedstock. Energy, Volume 33(11), pp. 1646–1653.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2008.06.002

Kusrini, E., Alhamid, M.I., Wulandari, D.A.,

Fatkhurrahman, M., Shahrin, E.W.E.S., Shahri, N.N.M., Usman, A., Prasetyo,

A.B., Sufyan, M., Rahman, A., Khoirina Dwi Nugrahaningtyas, K.D., Santosa, S.J., 2024a. Simultaneous

Adsorption of Multicomponent Lanthanide Ions on Pectin Encapsulated Zeolite A. EVERGREEN

Joint Journal of Novel Carbon Resource Sciences & Green Asia Strategy, Volume 11(1), pp. 371–378. https://doi.org/10.5109/7172296

Kusrini, E., Usman, A., Ayuningtyas, K., Wilson, L.D.,

Putra, N., Prasetyo, A.B., Rahman, A., Nugrahaningtyas, K.D., Santosa, S.J.,

Noviyanti, A.R., 2024b. Fragrance Carrier Based on Zeolite-A Modified Bentonite

as a Controlled Release System in Air Freshener Applications. Sains

Malaysiana, Volume 53(10), pp. 3499-3509. http://doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2024-5310-22

Kusrini, E., Hashim, F., Aziz, A., Hassim, M.F.N., Usman, A., Wilson, L.D., Negim, E.S., Prasetyo, A.B., 2024c. Potential of

Critical Mineral and Cytotoxicity Activity of Gadolinium Complex as Anti-amoebic

Agent by Viability Studies and Flow Cytometry Techniques. AUIQ Complementary

Biological System, Volume 1, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.70176/3007-973X.1010

Kusrini, E., Oktavianto, F., Usman, A., Mawarni, D.P.,

Alhamid, M.I, 2020a. Synthesis, Characterization, and Performance of Graphene

Oxide and Phosphorylated Graphene Oxide as Additive in Water-based Drilling

Fluids. Applied Surface Science, Volume 506, p. 145005.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.145005

Kusrini, E.,

Mualim, N.M., Usman, A., Setiawan, M.D.H., Rahman, A., 2020b. Synthesis,

Characterization and Adsorption of Fe3+, Pb2+ and Cu2+

Cations using Na-Zeolite A Prepared from Bangka Kaolin, In: AIP Conference Proceedings, Volume 2255, p. 060013. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0014317

Kusrini, E., Mualim, N.M., Rahman, A., Usman, A.,

2020c. Application

of Activated Na-zeolite as a Water Softening Agent to Remove Ca2+

and Mg2+ Ions from Water. In: AIP Conference Proceedings, Volume 2255, p. 060012. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0014314

Leung, D.Y., Wu, X., Leung,

M.K.H., 2010. A Review on Biodiesel Production using Catalyzed

Transesterification. Applied Energy, Volume 87(4), pp. 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2009.10.006

Majid, A.F.A., Dewi, R., Shahri, N.N.M., E., Shahrin, W.E.S., Kusrini,

E., Shamsuddin, N., Lim, J.-W., Thongratkaew, S., Faungnawakij, K., Usman, A.,

2023. Enhancing Adsorption Performance of Alkali Activated Kaolinite in the

Removal of Antibiotic Rifampicin from Aqueous Solution. Colloids and Surfaces A:

Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. Volume 676, p. 132209.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132209

Maneerung, T., Kawi, S., Dai, Y.,

Wang, C., 2016. Sustainable Biodiesel Production via Transesterification of

Waste Cooking Oil by using CaO Catalysts Prepared from Chicken Manure. Energy

Conversion and Management, Volume 123, pp. 487–497.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.06.071

Marso, T.M.M., Kalpage, C.S., M.Y. Udugala-Ganehenege,

M.Y., 2017. Metal modified graphene oxide composite catalyst for the production

of biodiesel via pre-esterification of Calophyllum inophyllum oil. Fuel, Volume

199, pp. 47-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.01.004

Nasrollahzadeh,

M., Jaleh, B., Jabbari, A., 2014. Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic

Activity of Graphene Oxide/ZnO Nanocomposites. RSC Advances, Volume

4(69), p. 36713. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA05833J

Rahma,

F.N., Hidayat, A., 2023. Biodiesel Production from Free Fatty Acid using ZrO2/Bagasse

Fly Ash Catalyst. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(1), pp.

206–218.

https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i1.4873

Santoro, S., Kozhushkov, S.I., Ackermann, L., Vaccaro,

L., 2016. ChemInform Abstract: Heterogeneous Catalytic Approaches in C-H

Activation Reactions. ChemInform, Volume 47(32).

https://doi.org/10.1039/C6GC00385K

Soetaredjo,

F.E., Ayucitra, A., Ismadji, S., Maukar, A.L., 2011. KOH/Bentonite Catalysts

for Transesterification of Palm Oil to Biodiesel. Applied Clay Science,

Volume 53(2), pp. 341–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2010.12.018

Subari, R.I.F. Wenas, R.I.F., Suripto., 2008. Industrial

Minerals in West Kalimantan and Their Utilization for Ceramic Products. Indonesian

Mining Journal, Volume 11(12), pp. 27 – 37.

Syukri,

S., Ferdian, F., Rilda, Y., Putri, Y.E., Efdi, M., Septiani, U. 2020. Synthesis

of Graphene Oxide Enriched Natural Kaolinite Clay and Its Application for Biodiesel

Production. International Journal of Renewable Energy Development,

10(2), pp. 307–315.

https://doi.org/10.14710/ijred.2021.32915

The

National Standardization Agency of Indonesia (BSN), 2015. Standar Nasional

Indonesia 7182:2015 Biodiesel (Indonesian National Standard 7182: 2015

Biodiesel). Indonesia, pp. 1–88.

Yan, S.,

DiMaggio, C., Mohan, S., Kim, M., Salley, S.O., Ng., K.S., 2010. Advancements

in Heterogeneous Catalysis for Biodiesel Synthesis. Topics in Catalysis,

Volume 53, pp. 721–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-010-9460-5

Yang,

B., Leclercq, L., Clacens, J.M., Nardello-Rataj, V., 2017. Acidic/amphiphilic

Silica Nanoparticles: New Eco-friendly Pickering Interfacial Catalysis for

Biodiesel Production. Green Chemistry, Volume 19(19), pp. 4552–4562.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C7GC01910F

Wahyono, Y., Hadiyanto, M.A., Budihardjo, Y.H., Baihaqi, R.A., 2022.

Multifeedstock Biodiesel Production from a Blend of Five Oils through

Transesterification with Variation of Moles Ratio of Oil: Methanol. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 13(3), pp. 606–618. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i3.4804

Whulanza, Y., Kusrini, E., 2024. Shaping a Sustainable Future: The Convergence of Materials Science, Critical Minerals and Technological Innovation. International Journal of Technology, Volume 15(1), pp. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i1.6934