Developing Machine Learning Model to Predict HVAC System of Healthy Building: A Case Study in Indonesia

Corresponding email: mustikasarisayuti@gmail.com

Published at : 07 Dec 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 7 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i7.6682

Sari, M., Berawi, M.A., Larasati, S.P., Susilowati, S.I., Susantono, B., Woodhead, R., 2023. Developing Machine Learning Model to Predict HVAC System of Healthy Building: A Case Study in Indonesia . International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(7), pp. 1438-1448

| Mustika Sari | Center for Sustainable Infrastructure Development, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

| Mohammed Ali Berawi | 1. Center for Sustainable Infrastructure Development, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia, 2. Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, I |

| Sylvia Putri Larasati | Center for Sustainable Infrastructure Development, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

| Suci Indah Susilowati | Center for Sustainable Infrastructure Development, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

| Bambang Susantono | Center for Sustainable Infrastructure Development, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

| Roy Woodhead | Sheffield Business School, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, S1 1WB, United Kingdom |

Sick

Building Syndrome (SBS) is the health and comfort issues experienced

by people during

the

time indoor. As urban

dwellers typically spend 90% of the time indoor, Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) becomes

essential.

Consequently, ensuring appropriate air exchange in building is essential, with Heating, Ventilation, and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) system

playing a crucial

ole in

maintaining indoor comfort. Therefore, this study

aimed to develop a

predictive machine learning (ML) model using Industry 4.0 technological advancements to optimize

HVAC system design that meets IAQ parameters in Indonesia healthy building

(HB). An extensive

literature review was

carried out to

identify IAQ parameters specific to Indonesia HB.

Furthermore, four ML models were developed using the RapidMiner Studio

application,

validated with the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and

confusion matrix methods. The results showed that

the cooling load and the chiller-type prediction models had a relative error of

1.11% and 3.33%.

Meanwhile, Air

Handling Unit (AHU) type and filter area predictive model had a relative error

of 10% and 1.22%, respectively. These errors showed the accuracy of ML

model in

predicting HVAC

system of HB.

Healthy building; Indoor air quality; Machine learning

Sick

Building Syndrome (SBS) is used to describe the sudden and severe discomfort or

illness experienced by occupants after spending time in building

IAQ is

essential as humans spend 90% of the time indoor

Healthy building (HB) has become a promising solution to address various environmental

and health-related concerns, minimizing adverse impacts on the health of occupants and the

surrounding environment. Among the critical indoor environmental issues demanding attention, IAQ is important in preventing negative

effects on the health and well-being of occupants (Sari et al., 2022). Additionally, elements such as thermal quality, lighting,

acoustics, privacy, security, and functional compatibility must be carefully

considered during the design, construction, and operation. HB concept is not well-developed in Indonesia, as evident from the absence of specific standards and

certifications, compared to the more established idea of

green building promoted by Green Building Council Indonesia (GBCI). This concept has gained substantial growth in wealthier nations including China, Europe, and the United States, evidenced by the prominence of certifications such as WELL

Building Standard, Fitwel, RESET, and LEED Indoor Air Quality Rating System, in

ensuring building positively contribute to the health and well-being of occupants (Lin et al., 2022).

All occupied buildings require an external air supply, which may need heating or cooling before distribution

to the occupied spaces depending on outdoor conditions. Concurrently, as

outside air is drawn into building, indoor air is exhausted or passively

discharged, effectively removing airborne contaminants. HVAC system, including heating, cooling, outdoor air filtration, and

humidity control, play a crucial role in maintaining the comfort of

occupants. However, poorly designed HVAC system in building has become a

significant source of poor IAQ.

In recent years, the

development of digital technology has

significantly impacted various industries, including building sector. Artificial

Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) models have also shown great potential for application in

building construction industry

Table 1 Collected data for

cooling load calculation

|

No. |

Building

Data |

Description |

|

1 |

The floor area of the air-conditioned space |

Collected data |

|

2 |

Height of the air-conditioned space |

Collected data |

|

3 |

Window

area |

Set

at a minimum of 10% of the floor as per SNI 03-6572-2001 |

|

4 |

Door

area | |

|

5 |

Wall area |

Collected data |

|

6 |

Roof/ceiling area |

Collected data |

|

7 |

Number of occupants |

Each person has a minimum of 7.5 m2

of space as per Ministry of Health Regulation No. 28/2019 |

|

8 |

Electrical power used by other equipment |

Energy Consumption Intensity standard for

the very efficient category with a power usage of less than 8.5 kWh/m2/month

following Regulation of the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources No.

13/2012 |

Cooling Load Temperature Difference (CLTD) method was used to calculate floor-specific cooling loads, determining HVAC components

influencing IAQ as ML model output. The method included inputting climate data

(location, outdoor and indoor temperatures, outdoor and indoor humidity,

elevation, and latitude) and building data (windows, doors, walls, and

ceilings) for heat gain calculations. Heat gain was calculated using U-value

(U) and Shading Coefficient (SC), representing the material heat transfer rate

and the thermal performance of single glass units in building, respectively.

U-value of the triple glass with Opaque Roller Shade was 0.72 BTUh/ft², and SC

was 0.36. Subsequently, Glass Load Factor (GLF) selection was evaluated based on window orientation and material. The formula for calculating heat based on window area (A) in each

orientation is expressed in Equation 1:

Where: q = heat

addition from solar radiation through the glass (MBTu/h)

A =

glass surface area (ft2)

GLF = Glass Load Factor (MBTu/h/ft2)

Heat gain from doors and walls was calculated using triple glass doors with U-value of 1.87 BTUh/ft² and plaster brick walls with U-value of 0.08 BTUh/ft². Heat gain from walls was determined using the formula in Equation 2:

Where: q = heat

addition from solar radiation through the door wall (MBTu/h)

U =

heat transfer coefficient (MBTu/(h·ft2·°F)

A =

wall surface area (ft2)

CLTD = wall coolant load temperature difference (°F)

Heat gain

from infiltration, occupants, and electrical devices was calculated using the

formula in Equation 3:

Where: q = sensible

heat addition from infiltrated air (MBTu/h)

Q =

ventilation in liters per second and infiltration (ft3/s)

= difference between the outside and

indoor air temperature

Q is calculated by the formula in Equation 4:

cupants, and electrical devices was calculated using the formula in Equation 3:

Where: V = Conditioned room volume (ft3)

ACH = Number

of air changes in a room in 1 hour

Heat gain from humans is calculated by multiplying the number of occupants

by the rate of heat gain, which is set at 475 Btu/hour according to SNI

03-6572-2001 for moderate activity office work, and the formula used is shown in Equation 5:

Where: N = Number of occupants

As the model output, the minimum filter area is crucial for preserving indoor pressure stability and air quality. It is determined by considering the ventilation rate of the room. Based on ASHRAE recommendation, the maximum filter ventilation rate is 150 ft/min for a 1-inch thick HEPA filter (MERV13). The formula is expressed in Equation 6

Q = Room

ventilation rate (ft2/s)

F =

Filter ventilation rate (ft/min)

RapidMiner, used for developing ML model, streamlines the

process through Auto

Model feature, automating

various stages:

- Data import: The initial stage

is to import relevant data into RapidMiner.

- Data cleansing: This includes

tasks such as managing missing values, data normalization, feature selection, data partitioning for training and

testing to ensure suitability for modeling.

- Auto Model Configuration: Users specify the target variable and

performance metric.

- Model Selection: Auto Model

explores various ML algorithms such as regression, classification, and clustering to identify the best model for the

target variable and performance metric.

- Model Training: Auto Model

optimizes model parameters and hyperparameters.

- Model Evaluation: After

training, Auto Model assesses the performance of each model on the validation dataset,

ranking based on the specified performance metric

- Model Deployment: The

best-performing model is selected for deployment, allowing prediction for new

unseen data.

After developing the model to predict output values

based on input data, the accuracy was assessed using Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

and the confusion matrix to calculate performance. MAE was used to compute absolute errors for all predictions and calculate the mean. This process was carried out by evaluating the mean of the dataset,

subtracting it from each data point, summing the results, and dividing by the

total number of datasets

Where: xi

n = the total number of values

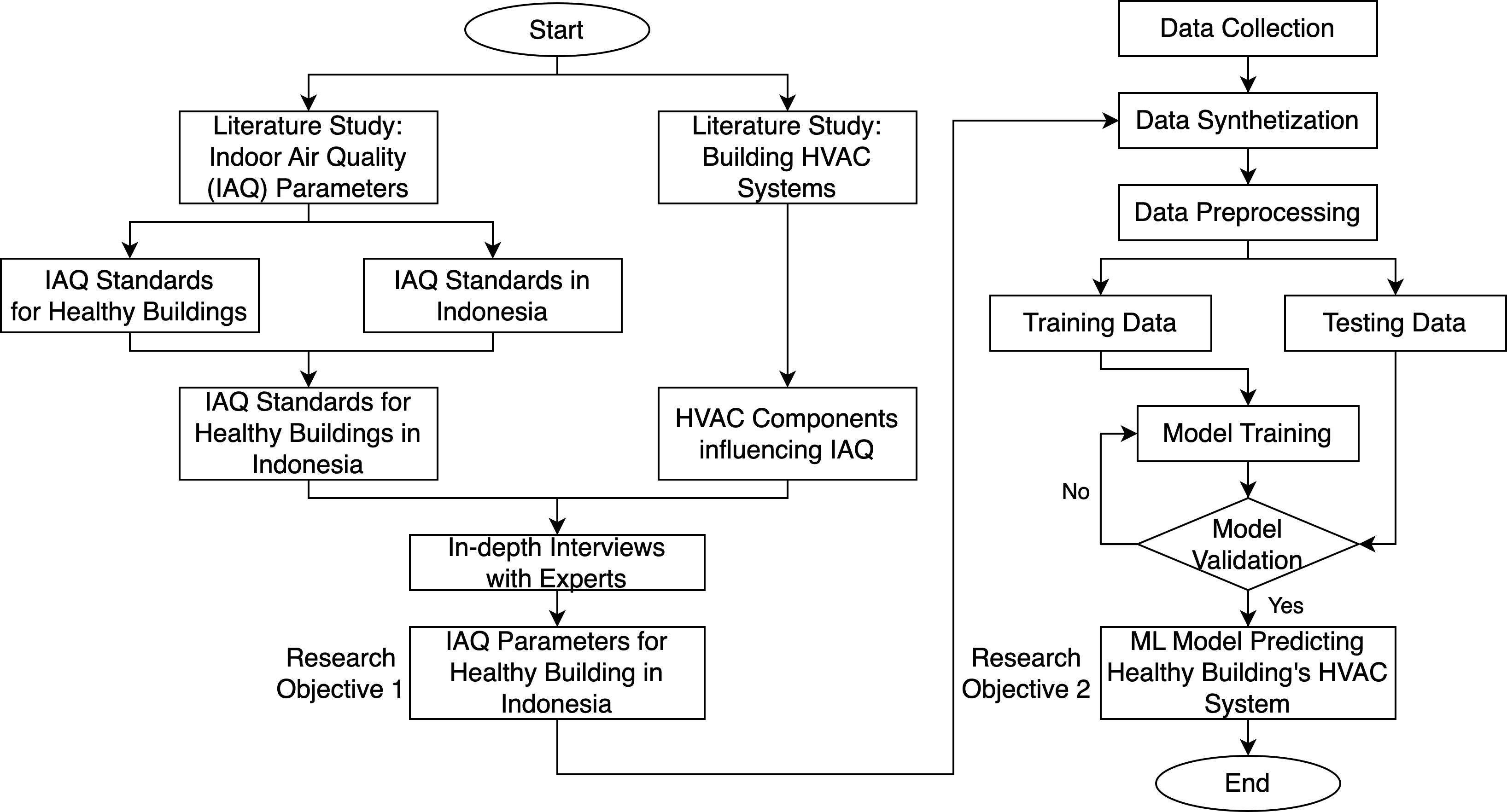

The confusion matrix visually represents the performance of the predictive model, detailing correct and incorrect predictions (Berawi et al., 2021). Precision and Recall are key indicators for accuracy assessment. Precision measures accurate predictions among all predicted data, while Recall assesses successful predictions relative to actual data. These indicators offer insights into the classification performance and ability to make accurate class predictions. The workflow for achieving the objectives of this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Study

Workflow

3.1. Identifying IAQ Parameters

for Healthy Building (HB) in Indonesia

A

literature review conducted

on related documents showed that there were various indicators used to measure IAQ of

HB. Moreover,

IAQ indicator in HB consisted of seven pollutants, namely Particulate

Matter (PM10), PM2.5, Radon, Ozone, Volatile Organic Compound (VOC), Nitrogen

Oxides (NO), and Carbon Monoxide (CO), negatively impacting human

health

Table 2 IAQ

parameters for HB in Indonesia

|

Indicators |

Threshold |

References |

|

CO2 |

1000 ppm (8h) |

ASHRAE/EPA |

|

PM10 |

50 |

WELL/LEED |

|

PM2.5 |

35 |

WELL; EPA; PMK No. 1077 |

|

NO2 |

100 ppb (1h) |

ASHRAE/EPA |

|

Radon |

4 pCi/L |

WELL/LEED; ASHRAE/EPA; OSHA |

|

Ozon |

0,07 ppm (8h) |

WELL/LEED; ASHRAE/EPA |

|

VOC |

500 |

WELL/LEED |

|

CO |

9 ppm (8h) |

WELL/LEED; ASHRAE/EPA; PMK No. 1077 |

Optimal IAQ

in HVAC system can be

achieved through ventilation and filtration. Ventilation, either

natural or mechanical, supplies and removes air, while filters are key in

removing particulates. Consequently, the impact of filters on room pressure is essential during the selection. In commercial and office buildings, a MERV13

filter is effective

during the filtration of

particles sized between 0.3-1.0 microns

Temperature and humidity also play a

significant effecting in determining IAQ.

Indoor temperature affects air movement and pollutant dilution, with high

temperatures potentially increasing VOC concentrations

Based on a literature study and in-depth

interviews with experts, chiller and Air Handling Unit (AHU) are key components

affecting temperature and humidity. Chiller is responsible for cooling the

rooms for comfortable temperatures, while AHU maintains humidity levels. Furthermore, the evaporator in AHU adds moisture to

conditioned air, regulating indoor humidity. Well-coordinated chiller and AHU

operation is essential for optimal temperature and humidity control for

building of occupants.

3.2. Developing Machine

Learning Models

3.2.1. Data

Preprocessing

The result of the first Research

Objective (RO) led to

the development of predictive ML model for four key outputs, namely 1) Cooling load, 2) Chiller

type, 3) AHU type, and 4) Minimum filter area. Initial preparation of building

data facilitated air conditioning load calculation for each floor, enabling the

selection of appropriate chiller and AHU types. focusing on a commonly used

chiller brand in Indonesia based on cooling load capacity, as

shown in Table 3.

The ventilation rate of the room determines the minimum filter area. According to ASHRAE recommendation, the maximum filter ventilation rate is 150 ft/min for a 1-inch filter thickness. After preprocessing the data, the modeling process included three stages, namely Importing, Auto Model, and Deployment. RapidMiner user-friendly interface and automation features streamline the creation and deployment of ML model efficiently.

Table 3 Cooling load

capacity of several Chiller and AHU types

|

Chiller |

|

AHU | ||||

|

No. |

Type |

Capacity

(kW) |

|

No. |

Type |

Capacity

(kW) |

|

1 |

EWAQ040 |

43.4 |

|

1 |

AHUR16 |

47.5 |

|

2 |

EWAQ050 |

51.8 |

|

2 |

AHUR20 |

59 |

|

3 |

EWAQ064 |

64.5 |

|

3 |

AHUR32 |

95.1 |

|

4 |

EWAQ075 |

74.7 |

|

4 |

AHUR40 |

110.2 |

|

5 |

EWAQ085 |

84.2 |

|

5 |

AHUR48 |

140.2 |

|

6 |

EWAQ100 |

96.7 |

|

6 |

AHUR60 |

177.4 |

|

7 |

EWAQ120 |

117 |

|

7 |

AHUR80 |

236.1 |

|

8 |

EWAQ140 |

139 |

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

EWAQ155 |

154 |

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

EWAQ180 |

178 |

|

|

|

|

3.2.2. Machine

Learning (ML) Model Development

This section presents the

development of predictive ML model, including 1) Cooling load, 2) Chiller type,

3) AHU type, and 4) Minimum filter area predictions. After the training data was

accessed and the predictors were selected through task selection, the required

attributes were imported to build the first prediction model for Cooling load.

RapidMiner played a crucial role by providing attribute quality indicators based on

correlation, ID-ness, stability, and missing values that significantly impacted

model performance. However, poor data quality could lead to overfitting, limiting predictions

to a narrow data range, or underfitting due to scattered data quality, impeding

accurate predictions.

ML algorithms considered in developing the first model included the Generalized Linear Model (GLM), Deep Learning (DL), Decision Trees (DT), Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT), and Support Vector Machine (CVM). As presented in Figure 2, model with the highest accuracy was identified through algorithm comparisons, assessing errors, standard deviations, and prediction times. For the first model, GLM outperformed others with a minimal relative error of 1.1%, while DT had the quickest prediction time.

Figure 2 Prediction

result of ML for cooling load

The second model followed the

same procedures that were previously used. Algorithms considered included Naïve Bayes

(NB), GLM, Logistic Regression (LR), Fast Large Margin (FLM), DL, DT, RF, GBT,

and SVM. Naïve Bayes showed the best performance with a 3.3% relative error,

while DL showed the fastest

runtime of 5 seconds.

Furthermore, Naïve Bayes

proved the most accurate for the third predictive model for AHU types, with a

10% classification error. Regarding the fourth model for minimum filter area, floor

area and ceiling height were used as inputs. Among models developed with

algorithms including LR, FLM, DL, DT, RF, GBT, and SVM, GLM showed excellent

performance with a 1.2%

relative error and the fastest runtime. GLM was selected as the most suitable

algorithm for models 1 and 4 due to the accuracy in predicting numerical values

in these models. Furthermore, Naïve Bayes, a classification algorithm, yielded the best results

for Models 2 and 3, as the output was in the form of classes.

3.2.3. Machine

Learning (ML) Model Evaluation

The assessment of the regression model accuracy included relative error and MAE, providing insights into the prediction error magnitude. For

example, in Model 1, MAE was 0.893, and 381.760 in Model 4. The accuracy for Models 2 and 3 was measured using

the confusion matrix due to the classification nature. The confusion matrix

showed that Model 2 achieved 100% accuracy in 9 out of 10 chiller types, with a 3.33%

classification error. Model 3 achieved 100% accuracy in 4 among 7 AHU types, resulting in a 10% classification error. Table 4 summarizes

the accuracy results of all developed models.

Table 4 The accuracy results

for ML models

|

Model |

Algorithm |

Relative/Classification

Error |

MAE |

|

1:

Cooling Load |

Generalized

Linear Model |

1.11% |

0.893 |

|

2:

Chiller Type |

Naïve Bayes |

3.33% |

- |

|

2:

AHU Type |

Naïve Bayes |

10% |

- |

|

4:

Filter Area |

Generalized

Linear Model |

1.22% |

381.760 |

The

developed ML model was deployed to show the predictive

capacity on new data. A particular building was used as the case study

with several specifications, accommodating 175 occupants. These included a total area of 1850 m2, ceiling height 3.1 meters, and ceiling area

matching the total area. Window sizes are specified

(north-facing: 15.5 m², east-facing: 16 m², south-facing: 16.5 m², west-facing:

15.7 m²), door sizes (north-facing: 6.5 m², east-facing: 2.1 m²,

south-facing: 6 m², west-facing: 7.8 m²), and wall

areas (north side: 97 m², east side: 96.2 m², south side: 95.6 m²,

and west side: 94 m²).

The

cooling load prediction from Model 1 was 102.297 kW, which was Models 2 and 3

to determine chiller type (EWAQ120) and AHU type (AHUR48), respectively.

Additionally, Model 4 predicted a minimum filter area of 4.084 m². As shown in

Figures 3, 4, and 5, the implementation of these predictions can effectively

optimize IAQ in Indonesian building, following HB concept.

Figure 3 Model

deployment: Cooling load prediction with ML Model 1

Figure 4 Model deployment: (a) Chiller and (b) AHU type prediction with ML Models 2&3

Figure 5 Model

deployment: Filter Area prediction with ML Model 4

In conclusion, this study

used ML to enhance HVAC system design, focusing on improving IAQ to achieve HB

concept. The two main objectives included identifying IAQ parameters for

Indonesian HB and developing ML model for HVAC system planning. Based on the results,

ML model successfully predicted the cooling load, chiller type, AHU type, and

filter area based on climate and building data. GLM algorithm was recommended

to predict cooling load and minimum filter area, while Naïve Bayes performed

best in forecasting chiller and AHU types. The implementation of these

predictions could effectively optimize IAQ, contributing to the reduction of

SBS incidence. This study did not specifically quantify the percentage by which

the incidence was reduced. Consequently, future study was recommended to

examine the reduction in SBS incidence resulting from the improved IAQ.

This

research is supported by the Riset dan Inovasi Indonesia Maju (RIIM) Grant

under contract number PKS-576/UN2.INV/HKP.05/2023, funded by the National

Research and Innovation Agency and Educational Fund Management Institution.

Allen,

J.G., Bernstein, A., Cao, X., Eitland, E., Flanigan, S., Gokhale, M., Goodman,

J., Klager, S., Klingensmith, L., Laurent, J.G.C., Lockey, S.W., 2017. The 9

Foundations of A Healthy Building. Harvard: School of Public Health

Babaoglu, U.T., Milletli-Sezgin, F., Yag, F., 2020. Sick Building Symptoms Among Hospital Workers Associated with

Indoor Air Quality and Personal Factors. Indoor and Built Environment,

Volume 29(5), pp. 645–655

Berawi,

M.A., Leviäkangas, P., Siahaan, S.A.O., Hafidza, A., Sari, M., Miraj, P.,

Harwahyu, R., Saroji, G., 2021. Increasing Disaster Victim Survival Rate:

Savemylife Mobile Application Development. International Journal of Disaster

Risk Reduction, Volume 60, p. 102290

Borda,

D., Bergagio, M., Amerio, M., Masoero, M.C., Borchiellini, R., Papurello, D.,

2023. Development of Anomaly Detectors for HVAC Systems Using Machine Learning.

Processes, Volume 11(2), p. 535

Dawangi,

I.D., Budiyanto, M.A. 2021. Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan Development

Using Machine Learning: Case Study of CO2 Emissions of Ship Activities at

Container Port. International Journal of Technology, Volume 12(5), pp.

1048–1057

Hodson,

T.O., 2022. Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) Or Mean Absolute Error (MAE): When to

Use Them or Not. Geoscientific Model

Development, Volume 15(14), pp. 5481–5487

Hong,

T., Wang, Z., Luo, X., Zhang, W., 2020. State-Of-The-Art On Research and

Applications of Machine Learning in The Building Life Cycle. Energy and

Buildings, Volume 212, p. 109831

László,

K., Ghous, H., 2020. Efficiency Comparison of Python and RapidMiner. Multidiszciplináris

Tudományok, Volume 10(3), pp. 212–220

Li,

M., 2020. Optimizing HVAC Systems in Buildings with Machine Learning Prediction

Models: An Algorithm Based Economic Analysis. In: 2020 Management

Science Informatization and Economic Innovation Development Conference, pp.

210–217

Lin,

Y., Yuan, X., Yang, W., Hao, X., Li, C., 2022. A Review on Research and

Development of Healthy Building in China. Buildings, Volume 12, p.

376

Liu,

J., Yang, X., Meng, X., Liu, Y., 2018. Effects of Indoor Temperature and Air

Movement on Perceived Air Quality in the Natural Ventilated Classrooms. In:

International High Performance Building Conference, pp. 1–11

Lubis,

F.F., Mutaqin, Putri, A., Waskita, D., Sulistyaningtyas, T., Arman, A.A.,

Rosmansyah, Y., 2021. Automated Short-Answer Grading using Semantic Similarity

based on Word Embedding. International Journal of Technology, Volume

12(3), pp. 571–581

Mentese,

S., Mirici, N.A., Elbir, T., Palaz, E., Mumcuoglu, D.T., Cotuker, O., Bakar,

C., Oymak, S., Otkun, M.T., 2020. A Long-Term Multi-Parametric Monitoring

Study: Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) and The Sources of The Pollutants, Prevalence

of Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) Symptoms, And Respiratory Health Indicators. Atmospheric

Pollution Research, Volume 11(12), pp. 2270–2281

Sari,

M., Berawi, M.A., Zagloel, T.Y., Amatkasmin, L.R., Susantono, B., 2022. Machine

Learning Predictive Model for Performance Criteria of Energy-Efficient Healthy

Building. In: Innovations in Digital Economy, Rodionov, D.,

Kudryavtseva, T., Skhvediani, A., Berawi, M.A. (ed.), Springer, Communications

in Computer and Information Science, Volume 1619

The

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), 2003. Guidance

for Filtration and Air-Cleaning Systemsto Protect Building Environments from

Airborne Chemical, Biological, or Radiological Attacks. Available online at

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2003-136/default.html, Accessed on April 20,

2022

Triadji,

R.W., Berawi, M.A., Sari, M., 2023. A Review on Application of Machine Learning

in Building Performance Prediction. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Volume

225, pp. 3–9

US

Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), 2017. Healthy Buildings, Healthy

People: A Vision to the 21st Century. USA: Createspace

Independent Publishing Platform

Whulanza,

Y., Kusrini, E., 2023. Defining Healthy City and Its Influence on Urban

Well-being. International Journal of Technology, Volume 14(5), pp.

948–953

Zhang,

L., Cheng, Y., Zhang, Y., He, Y., Gu, Z., Yu, C., 2017. Impact Of Air Humidity

Fluctuation on The Rise of PM Mass Concentration Based on The High-Resolution

Monitoring Data. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, Volume 17(2), pp.

543–552

Zheng,

J., Ling, Z., Kang, Y., You, L., Zhao, Y., Xiao, Z., Chen, X., 2021. HVAC Load

Forecasting in Office Buildings Using Machine Learning. In: 2021 6th

International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy, pp. 877–881