Preliminary Study on the Fabrication of Multi-Layer Screen-Printed Electrode for Biosensor Application

Corresponding email: fauziyah17@ui.ac.id

Published at : 30 Dec 2022

Volume : IJtech

Vol 13, No 8 (2022)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i8.6124

Alfarobi, H., Yulianti, E.S., Intan, N., Whulanza, Y., Park, D.-H., Rahman, S.F., 2022. Preliminary Study on the Fabrication of Multi-Layer Screen-Printed Electrode for Biosensor Application. International Journal of Technology. Volume 13(8), pp. 1692-1703

| Habib Alfarobi | Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, West Java 16424 Indonesia |

| Elly Septia Yulianti | Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, West Java 16424 Indonesia |

| Nurul Intan | Research Center for Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, West Java 16424 Indonesia |

| Yudan Whulanza | 1. Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, West Java 16424 Indonesia, 2. Research Center for Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineerin |

| Don-Hee Park | 1. Interdisciplinary Program of Bioenergy and Biomaterial Engineering, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 500-757, Republic of Korea, 2. Department of Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Chonnam Natio |

| Siti Fauziyah Rahman | 1. Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, West Java 16424 Indonesia, 2. Research Center for Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineerin |

A biosensor is an analytical device that combines certain biological and

physical elements. Several types of transducers are used for physical elements,

such as optical, electrochemical, thermic, or gravimetric. Nowadays,

electrochemical transducers have become widely used for the application of

biomedical sensors. Electrochemical measurement devices called screen-printed

electrodes (SPEs) are created by printing several types of ink on a ceramic or

plastic substrate. SPEs enable speedy in-situ examination with high

repeatability, sensitivity, and accuracy. In this study, SPEs were fabricated

using a personalized CNC machine with carbon conductive ink as the electrode and

polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as the substrate. The mask, stencil, and

screen-printing dimensions were measured using a DinoLite microscope. SPEs

characterization was performed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to observe the surface

morphology. This simple approach method shows a promising result that SPEs can be produced up to 5 screen printing layers with the ability to flow the electrical current under a resistance of

350.4 K.

Biosensor; Electrochemical; PET; Screen-printed electrode

The screen-printed

electrode is an electrode arrangement commonly used in biomedical sensor applications,

consisting of a working electrode, reference electrode, and counter electrode.

The screen-printing technique uses a mesh to support the stencil and an

emulsion to hold the ink. During the screen-printing process, the squeegee will

move across the screen stencil to press a printed material (i.e., ink)

through the mesh. In printing multiple layers of ink, it is necessary to ensure

that the previously printed ink is first thermally compacted. Finally, it is

possible to apply protective ink to isolate the conductive path between the

electrodes (Li et al., 2012).

A procedure to improve the electrode layer is pretreatment on a

polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate. The main objective of the treatment

is to remove the insulating polymer on the polyethylene (Haque et al.,

2017), and

increase the surface roughness. In addition, this treatment ensures the

precision and quality of screen-printing results, where ink adhesion can be

greatly affected by the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of the substrate. In

addition, the hydrophilicity of the suitable substrate is favorable for the

adhesion of carbon inks and adds to the excellent electrochemical performance (Du et al., 2016).

SPEs for biosensor applications have been developed with various

materials and modifications to detect specific analytes. Table 1 describes in

detail various studies related to SPE, which are explicitly used as electrodes

for dopamine biosensors, and includes some characteristics of each

modification.

Table 1 Recent studies of SPCE in dopamine biosensor applications.

Some of the summaries

above show how powerful SPCE performance is when applied to the dopamine

biosensor. In addition, research conducted by Charmet et al. also shows that

the homemade method of fabrication with a simple approach can also produce

sensors with competitive performance (Charmet et al.,

2020). In the formation of SPCE, research

conducted by Randviir et

al. used a screen-printing method with silver/silver chloride as a reference

electrode (Randviir et al.,

2014). The next layer is

carbon ink printed on a counter layer and working electrode, as well as a

liaison between the three electrodes printed on a flexible polyester (PE)

substrate. Subsequently, the dielectric paste will be printed on the substrate

and dried at 60? for 30 minutes before the SPCE is ready for use. This study aimed to

fabricate screen printing electrodes using a personalized CNC machine for

screen printing purposes using conductive carbon as electrode ink and

polyethylene terephthalate (PET) as substrate.

Conductive carbon ink was purchased from

mjstation (Tangerang). Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) was purchased from the

Emake store (China). Screen emulsion liquid (photoxol 188), screen printing

sensitizer, superxol m-3 diluent, superxol 3 stencil remover, T180 mesh screen,

and screen-printing squeegee were purchased from Provenio Indonesia. The

voltammetric characterization used EmStat4s LR with the PSTrace 5.9 interface

(PalmSens, Netherlands). A personalized CNC 3018 Pro tabletop machine for

screen printing and an HP LaserJet Pro MFP M117fw printer for making masks were

obtained from the Manufacturing Research Center (MRC FTUI).

2.1. Electrochemical Cell

Design

Figure 1 is an electrochemical

cell design using the Inventor 3D design application. The electrochemical

cell's geometry follows a typical electrochemical cell geometry (de Araujo &

Paixão, 2014), with modifications to the electrode legs

to match the PalmSens SPE adapter.

Figure 1 Electrochemical

cell geometry design

2.2. Screen-Printing Mask

Fabrication

The

electrochemical cell design will be printed on Yashica transparent paper. The

process uses an HP LaserJet Pro MFP M117fw printer. The result of the electrochemical

cell design on Yashica transparent paper is called a mask. The mask is then

used to make stencils for screen printing using photolithography.

2.3. Screen-Printing Stencil

Fabrication

Screen

printing is coated with screen emulsion liquid (Superxol 188) mixed with a

sensitizer in a successive ratio of 5:1, then mixed and poured over the screen

evenly. Furthermore, it will be dried at low light intensity at room

temperature for 25 minutes, followed by the transfer of the design from the

mask to the screen printing by a photolithography method using a 40-watt lamp

for 14 minutes. In the following process, the development process will be

carried out by flushing the formed SPE with pressurized water to identify the screen's resistance.

2.4. Screen-Printing Process

Figure 2

shows a screen-printing scheme with carbon as the ink paste for the process.

The substrate used is polyethylene terephthalate (PET). The printing process

takes place using a personalized CNC 3018 Pro machine. It occurs when the

squeegee presses the screen to initiate contact between the screen and the

substrate, and the ink will be pushed down into the opening, a permeable area

that forms the desired image.

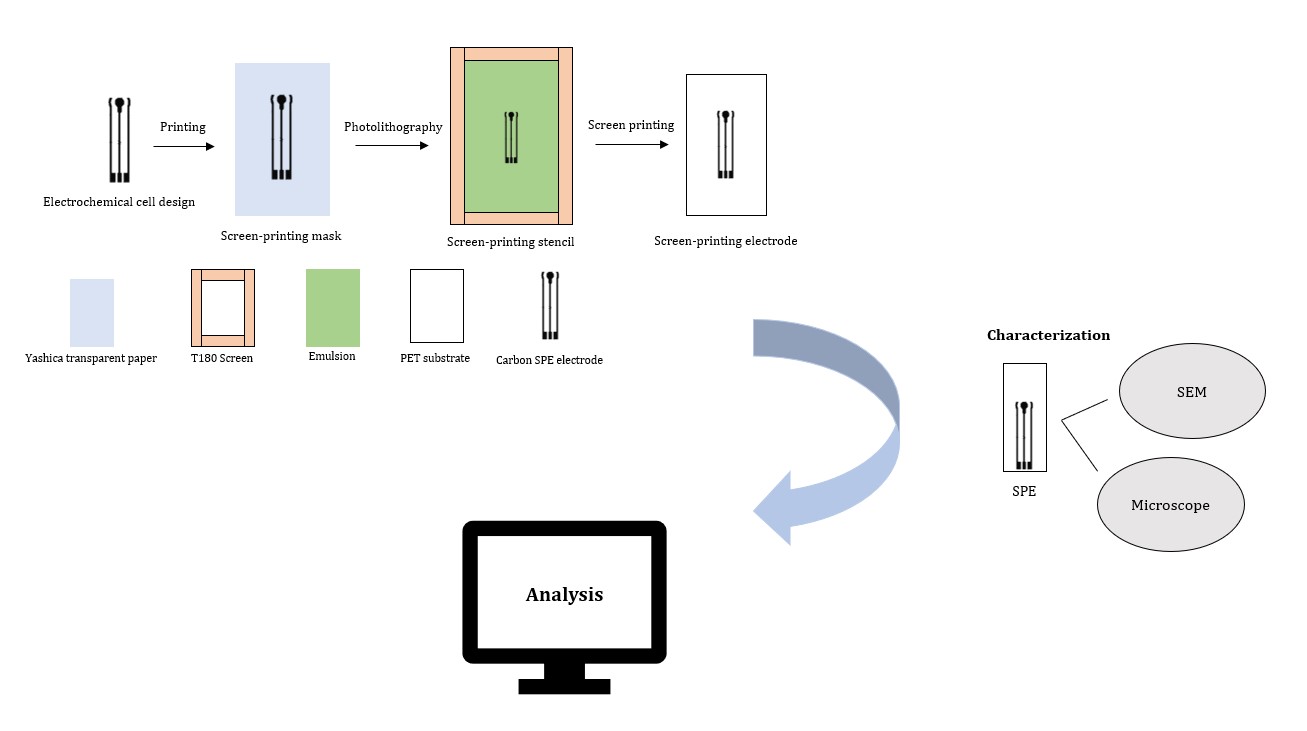

Parameters in the screen-printing process are the mesh screen size, the snap off-distance, and the number of layers of screen printing. The mesh screen size used is T180, where the code T (tick) is a term commonly used in Asia to denote the number of threads sewn every 1 cm. The higher T value results in tighter stitches and more precise screen printing. Snap-off distance is the distance between the substrate and the screen printing; while the snap-off distance applied in this study is 2.5mm, and the screen-printing process layer consists of 5 layers. Each layer of the ink screen printing process is dried for 15 minutes at room temperature, followed by 30 minutes of drying at a temperature of 70? C after the desired number of layers has been achieved. The overall process of fabricating the screen printing electrode is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Fabrication of screen printing electrode

3.1. Screen-printing Stencil

The irradiation time was varied in the stencil fabrication process on the T180 screen.

There is a difference in the results of the stencil formation at each time variation. The irradiation time that formed the best stencil was 14 minutes. Within 8 to 12 minutes, the emulsion on the screen was damaged and did not form the desired SPE stencil when the development process was applied with pressurized water. Meanwhile, at 16 to 18 minutes, the emulsion on the screen is challenging to develop due to prolonged irradiation time. The optimum duration for irradiation is 14 minutes. Figure 3 shows the photolithographic process using a 40-watt light source. The light source consists of five T5 LED lamps arranged in parallel. Lighting level affects irradiation time to get appropriate stencil. The higher lighting level requires less irradiation time. However, if the irradiation time is too long, the development process cannot occur.

Figure 3 Photolithography process

3.2. Microscope

The mask observation for screen-printing was measured using a DinoLite microscope. It is done on the straight-line section of the SPE. Figure 4 shows the results of mask measurements for screen printing.

Figure 4 Screen printing mask dimension

The print quality using the HP LaserJet Pro MFP M117fw printer is relatively acceptable. The mask works well since it can withstand the light from the photolithography process to produce a stencil on the screen.

Figure 5 Dimensional comparison graph of the initial design and the printed mask.

In this process, there are dimensional differences between the initial design and the printed mask. Figure 5 shows the print capability of the HP LaserJet Pro MFP M117fw printer on YASHICA paper. The most significant deviation between the design and print dimensions is 0.485 mm, and the slightest deviation is 0.469 mm. So, it can be concluded that the HP LaserJet Pro MFP M11fw printer machine can print an average dimension of approximately 0.977±0.008 mm (977 µm).

The screen printing stencils used in fabricating 5-layer SPE required a set with a mesh size of T180 and a snap-off distance of 2.5 mm. The following stencil results from photolithography using a mask, as described previously. Figure 6 shows changes in the dimensions of the stencil when it is used for the screen-printing process ten times.

Figure 6 Dimensional comparison of (a) the initial stencil and (b) the stencil after ten times use

It is seen that the initial stencil dimensions are similar to the mask size. The change in dimension is because the stencil edges are not perfectly exposed to the light source due to the diffused light source during the photolithography process. It causes the particular area to not be scattered apart during the development process. Figure 6b shows that the Dimensional changes after the screen printing process that can be caused by multiple cleaning of the screen from ink. In the screen printing process, the screen needs to be cleaned with superxol M-3 liquid each time. When used repeatedly, the liquid possibly removes or damages the hardened emulsion liquid on the screen. When the layers increase, the dimensions tend to be larger than the previous layer.

Figure 7 depicts the difference between the initial stencil's average width and the stencil's width after ten times use.

Figure 7 Dimension comparison graph of initial and ten times use a stencil

The average dimensions of the initial stencil T180 are approximately 0.742±0.031 mm (742 µm), and the dimensions of the stencil after ten uses are approximately 1.084±0.127 mm. The dimensional deviation between the mask and the initial stencil was 13.64%, while the stencil after ten uses was 18.69%.

The screen-printing process involves polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrates with different coating levels.

Figure 8 SPE screen printing of the (a) first and (b) second layers

The results of the observations between the first and second layers of the prepared SPEs are shown in Figures 8a and 8b. The PET substrate has a hydrophobic character and low compound absorption, which causes the insufficient formation of the carbon ink base (Zhang et al., 2021). In order to further improve the hydrophilicity of PET substrate, O2 plasma technique can be performed (Du et al., 2016).

Figure 9 SPE screen printing of the (a) third and (b) fourth layers

However, it gradually improves as the number of layers increases. Results of SPE observations third layer (Figure 9a) has a better structure than the first and second layers since its carbon ink already has a stronger base than the previous layers. Figure 9b shows that the side part of the fourth layer is unacceptable due to changes in the stencil's shape from repeated cleaning with superxol M-3 liquid. The carbon ink density of the two layers above is more promising than the previous ones, but it is still unsatisfactory to detect the current.

When the fifth layer was fabricated, the density of the electrodes increased, but there was a visually significant change in size. Figure 10 shows an unsatisfactory result compared to the expected design on the surface of the fifth layer, particularly on the side of the electrode path. As described earlier, it is caused by a change in the stencil's shape.

Figure 10 SPE screen printing fifth layers

When the fifth layer was fabricated, the density of the electrodes increased, but there was a visually significant change in size. Figure 10 shows an unsatisfactory result compared to the expected design on the surface of the fifth layer, particularly on the side of the electrode path. As described earlier, it is caused by a change in the stencil's shape.

From this phenomenon, the average width of the dimensions for each additional layer can be observed. Figure 11 shows that the higher the layer on the PET substrate, the larger the dimensions. Significant dimensional changes can be seen once the SPE reaches the fourth layer. These dimensional changes can occur due to the repeated use of superxol m-3 liquid. The average dimension in the first layer is 0.977±0.148 mm; 1.022±0.145 mm in the second layer, 1.105±0.074 mm in the third layer, 1,298±0.146 mm in the fourth layer; and 1.536 ± 0.184 mm in the fifth layer.

Figure 11 Thickness dimension comparison graph of resulting SPE in each layer

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Cross-sectional testing using SEM was conducted to determine the change in thickness dimensions of the screen printing on the first and fifth layers. Figure 12a shows that the consistency of carbon ink on the PET substrate is not satisfactory at the first layer. It shows that the limitation in the SPE manufacturing base layer will prevent the current from passing through the SPE. Figure 12b shows that the carbon ink density at the fifth layer looks more acceptable but still develops varying heights.

Figure 12 SEM image of the prepared SPE (a) first and (b) fifth layers

Figure 13 shows that the fifth layer has a reasonably significant thickness deviation influenced by the arrangement of the previous layers. The most substantial effect is due to the first layer, an SPE base with poor density, which causes a significant difference in the height of the following layers. Therefore, the fifth layer has a considerable deviation in thickness.

Figure 13 Thickness dimension comparison graph of SPE first and fifth layers

In addition, the SEM was carried out from the cross-sectional view, while research conducted by Randviir et al. performed SEM testing from the top view and tested several SPE models, namely edge plane-like SPE (ESPE), basal plane-like SPE (BSPE), and graphene SPE (GSPE) (Randviir et al., 2014). ESPE and GSPE have relatively rough and irregular surface characteristics, while BSPE has a smoother surface than ESPE and GSPE.

Based on the work

that has been demonstrated, it can be concluded that the SPE

fabrication process using carbon ink on a PET substrate can be up to 5 layers

but still has not achieved the geometric results according to the initial

design. The fabrication process in the first and second layers has a low ink

density, and the current has been unable to pass through the electrode path due

to the hydrophobic nature of the substrate. In the third layer, SPE has a

better characteristic than the previous layer because it has more robust

surface roughness than the previous layer, resulting in a better bond of carbon

ink on the third layer. In the fourth and fifth layers, the stencil has been

deformed due to the multiple screen cleanings, which increased the electrode

width. In the fifth layer, the current can be generated with a resistance of

350.4 K?. The morphological characterization of SPEs presented using SEM shows

that the fifth layer has a significant thickness deviation influenced by the

arrangement of the previous layers. This work can be used as an initial step to

conduct further research on SPEs fabrication, which can later be beneficial in

various applications.

We gratefully

acknowledge the funding from Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan

Teknologi through Penelitian Dasar Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi (PDUPT) 2022 No.

NKB-860/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2022.

Abdi,

M.M., Azli, N.F.WM., Chaibakhsh, N., Lim, H.N., Tahir, P.M., Karimi,

G.,Khorram, M., 2021. Nonenzymatic Dopamine Biosensor Based on

Tannin Nanocomposite. Journal of Polymer Science, Volume 59(5), pp.

428–438

Altun,

M., Bilgi Kamaç, M., Bilgi, A., Yilmaz, M., 2020.

Dopamine Biosensor Based on Screen-Printed Electrode Modified with Reduced Graphene Oxide, Polyneutral Red and

Gold Nanoparticle. International Journal of Environmental Analytical

Chemistry, Volume 100(4), pp. 451–467

Beitollahi,

H., Dourandish, Z., Ganjali, M.R., Shakeri, S., 2018.

Voltammetric Determination of Dopamine in the Presence of Tyrosine Using

Graphite Screen-Printed Electrode Modified with Graphene Quantum Dots. Ionics,

Volume 24(12), pp. 4023–4031

Cagnani,

G.R., Ibáñez-Redín, G., Tirich, B., Gonçalves, D., Balogh, D.T., Oliveira, O.N., 2020. Fully-printed Electrochemical Sensors

Made with Flexible Screen-Printed Electrodes Modified

By Roll-To-Roll Slot-Die Coating. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, Volume

165, p. 112428

Charmet, J., Rodrigues, R.,

Yildirim, E., Challa, P.K., Roberts,

B., Dallmann, R., Whulanza, Y., 2020.

Low-Cost Microfabrication Tool Box. Micromachines, Volume 11(2), p. 135

Chelly,

S., Chelly, M., Zribi, R., Gdoura, R., Bouaziz-Ketata, H., Neri, G., 2021. Electrochemical Detection of Dopamine and

Riboflavine on a Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode Modified by AuNPs Derived from

Rhanterium suaveolens Plant Extract. ACS Omega, Volume 6(37), pp.

23666–23675

de

Araujo, W.R., & Paixão, T.R.L.C., 2014.

Fabrication of Disposable Electrochemical Devices Using Silver Ink and Office

Paper. The Analyst, Volume 139(11), pp. 2742–2747

Du,

C.X., Han, L., Dong, S.L., Li, LH., Wei, Y., 2016.

A Novel Procedure for Fabricating Flexible Screen-Printed Electrodes with

Improved Electrochemical Performance. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science

and Engineering, Volume 137, p. 012060

Gu, M.,

Xiao, H., Wei, S., Chen, Z., Cao, L., 2022.

A Portable and Sensitive Dopamine Sensor Based on Aunps Functionalized ZnO-rGO

Nanocomposites Modified Screen-Printed Electrode. Journal of

Electroanalytical Chemistry, Volume 908, p. 116117

Gupta,

P., Goyal, R.N., Shim, Y.-B., 2015.

Simultaneous Analysis of Dopamine and

5-Hydroxyindoleacetic Acid at

Nanogold Modified Screen Printed Carbon Electrodes. Sensors and Actuators B:

Chemical, Volume 213, pp. 72–81

Haque, S.M., Rey, J.A.A., Masúd, A.A., Umar, Y.,

Albarracin, R., 2017. Electrical Properties of Different

Polymeric Materials and their Applications: The Influence of Electric Field. In

B. Du (Ed.), Properties and Applications of Polymer Dielectrics. InTech

Hua, Z.,

Qin, Q., Bai, X., Wang, C., Huang, X., 2015.

?-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex as the Immobilization

Matrix for Laccase in the Fabrication of a Biosensor

for Dopamine Determination. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, Volume

220, pp. 1169–1177

Ibáñez-Redín,

G., Wilson, D., Gonçalves, D., Oliveira, O.N., 2018.

Low-Cost Screen-Printed Electrodes Based on Electrochemically Reduced Graphene

Oxide-Carbon Black Nanocomposites for Dopamine, Epinephrine and Paracetamol

Detection. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Volume 515, pp.

101–108

Kanyong,

P., Rawlinson, S., Davis, J., 2016.

A Voltammetric Sensor Based on Chemically Reduced Graphene Oxide-Modified

Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode for the Simultaneous Analysis of Uric Acid,

Ascorbic Acid and Dopamine. Chemosensors, Volume 4(4), p. 25

Keyan,

A.K., Yu, C.-L., Rajakumaran, R., Sakthinathan, S., Wu, C.-F., Vinothini, S.,

Ming Chen, S.,Chiu, T.-W., 2021. Highly Sensitive and Selective

Electrochemical Detection of

Dopamine based on CuCrO2-TiO2 Composite Decorated

Screen-Printed Modified Electrode. Microchemical Journal, Volume 160,

pp. 105694

Ku, S.,

Palanisamy, S., Chen, S.-M., 2013.

Highly Selective Dopamine Electrochemical Sensor Based on Electrochemically

Pretreated Graphite and Nafion Composite Modified Screen Printed

Carbon Electrode. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Volume 411,

pp. 182–186

Kunpatee,

K., Traipop, S., Chailapakul, O., Chuanuwatanakul, S., 2020. Simultaneous Determination of Ascorbic

Acid, Dopamine, and Uric Acid Using Graphene Quantum Dots/Ionic

Liquid Modified Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode. Sensors and Actuators B:

Chemical, Volume 314, p. 128059

Li, M.,

Li, Y.-T., Li, D.-W., Long, Y.-T., 2012.

Recent Developments and Applications of

Screen-Printed Electrodes in

Environmental Assays—A Review. Analytica Chimica Acta, Volume

734, pp. 31–44

Ping,

J., Wu, J., Wang, Y., Ying, Y., 2012.

Simultaneous Determination of Ascorbic Acid, Dopamine and Uric Acid Using

High-Performance Screen-Printed Graphene Electrode. Biosensors and

Bioelectronics, Volume 34(1), pp. 70–76

Ping,

J., Wu, J., Ying, Y., 2010. Development of an Ionic Liquid Modified

Screen-Printed Graphite Electrode and

Its Sensing in Determination of

Dopamine. Electrochemistry Communications, Volume 12(12), pp. 1738–1741

Raj, M.,

Gupta, P., Goyal, R.N.,Shim, Y.-B., 2017.

Graphene/Conducting Polymer Nano-Composite Loaded Screen Printed Carbon Sensor for Simultaneous Determination of Dopamine and

5-Hydroxytryptamine. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, Volume 239, pp.

993–1002

Randviir,

E.P., Brownson, D.AC., Metters, J.P., Kadara, R.O.,

Banks, C.E., 2014. The Fabrication, Characterisation and

Electrochemical Investigation of

Screen-Printed Graphene Electrodes. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics,

Volume 16(10), pp. 4598–4611

Stoytcheva,

M., Zlatev, R., Gonzalez Navarro, F.F., Velkova, Z., Gochev, V., Montero, G.,

Ayala Bautista, A.G., Toscano-Palomar, L., 2016.

PVA-AWP/Tyrosinase Functionalized Screen-Printed Electrodes for Dopamine Determination.

Analytical Methods, Volume 8(26), pp.

5197–5203

Tavella,

F., Ampelli, C., Leonardi, S., Neri, G., 2018.

Photo-Electrochemical Sensing of Dopamine by a Novel Porous TiO2 Array-Modified

Screen-Printed Ti Electrode. Sensors, Volume 18(10), p. 3566

Varodi,

C., Pogacean, F., Gheorghe, M., Mirel, V., Coros, M., Barbu-Tudoran, L.,

Stefan-van Staden, R.-I., Pruneanu, S., 2020.

Stone Paper as a New Substrate to Fabricate Flexible Screen-Printed Electrodes

for the Electrochemical Detection of Dopamine. Sensors, Volume 20(12),

p. 3609

Zhang,

Y., Ying, L., Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Xu, Q., Li, C., 2021.

Unexpected Hydrophobic to Hydrophilic Transition of

PET Fabric Treated in a Deep Eutectic Solvent of

Choline Chloride and Oxalic Acid. Polymer, Volume 234, p. 124246

Zhang, Y.-M., Xu, P.-L., Zeng, Q., Liu, Y.-M., Liao, X., Hou, M.-F., 2017. Magnetism-Assisted Modification of Screen Printed Electrode with Magnetic Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for Electrochemical Determination of Dopamine. Materials Science and Engineering: C, Volume 74, pp. 62–69

Zribi, R., Maalej, R., Gillibert, R., Donato, M.G., Gucciardi, P.G., Leonardi, S.G., Neri, G., 2020. Simultaneous And Selective Determination of Dopamine and Tyrosine in the Presence of Uric Acid With 2D-Mos2 Nanosheets Modified Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes. FlatChem, Volume 24, p. 100187