Comparison of Phase Change Materials of Modified Soy Wax using Graphene and MAXene for Thermal Energy Storage Materials in Buildings

Corresponding email: nandyputra@eng.ui.ac.id

Published at : 09 May 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 3 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i3.6092

Trisnadewi, T., Kusrini, E., Nurjaya, D.M., Paul, B., Thierry, M., Putra, N., 2023. Comparison of Phase Change Materials of Modified Soy Wax using Graphene and MAXene for Thermal Energy Storage Materials in Buildings. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(3), pp. 596-605

| Titin Trisnadewi | Applied Heat Transfer Research Group, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java 16424, Indonesia |

| Eny Kusrini | Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java 16424, Indonesia |

| Dwi Marta Nurjaya | Department of Metallurgical and Material, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, 16424 Depok, West Java, Indonesia |

| Byrne Paul | Civil and Mechanical Engineering Laboratory LGCGM, University of Rennes, Rennes, France, 35704 |

| Maré Thierry | Civil and Mechanical Engineering Laboratory LGCGM, University of Rennes, Rennes, France, 35704 |

| Nandy Putra | Applied Heat Transfer Research Group, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java 16424, Indonesia |

This

study aimed to characterize Phase Change Materials (PCM) by improving their

properties using shape stabilization; this was achieved by adding nanoparticles

as a support material. PCM soy wax was modified using two nanoparticles,

graphene, and MAXene Ti3AlC2. The synthesis process

comprised stirring using a magnetic stirrer and ultrasonication using an

ultrasonic processor with various percentages of 0.1, 0.5, and 1 wt.% of soy

wax with nanoparticles. Based on the results, the morphologies of graphene and

MAXene Ti3AlC2 were found to be in the form of sheets.

These sheets had a large surface area, so soy wax could adsorb more

nanoparticles to increase the stability of the material. The thermal

conductivity increased with increasing percentage addition of nanoparticles. The

highest values from the synthesis with graphene and MAXene Ti3AlC2 were 0.89 W/mK and 0.85 W/mK, respectively. The thermal conductivity of soy wax

increased with the ratio of pure soy wax and nano-soy wax; the thermal

conductivity was 6.01 for soy wax+graphene and 5.71 for soy wax+Ti3AlC2.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) results showed an increase in the

melting and solidifying points of pure soy wax. The modified soy wax with 0.1

wt.% graphenes experienced a reduction in the melting and solidification points

up to 15% and 14%, respectively. Similar results were obtained for 0.1 wt.%

MAXene Ti3AlC2. In this case, there was a reduction in

the melting and solidifying points by 16% and 13%, respectively. Finally, the

addition of MAXene improved the material stability and thermal conductivity of

soy wax and has the potential to be used as a thermal energy storage material

for building applications.

Graphene; MAXene; Phase change material; Soy wax; Thermal energy storage

The ever-increasing world population, combined with the considerable increase in energy demand, has resulted in an environmental crisis (Vennapusa et al., 2020). One sector that consumes a significant amount of energy is buildings, where the maximum energy is utilized for the heating and cooling systems (Imessad et al., 2014). The demand for the installation of cooling systems in buildings is growing rapidly in the tropics. This is because the climate zones that receive large amounts of solar radiation have longer sunny days, high humidity, and high temperatures (Al-Obaidi et al., 2014). According to the Regulation of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia 2011, it states that the standard temperature range for comfort buildings in Indonesia is 18-30oC. Heat absorption in buildings that are quite high in the tropics causes uncomfortable conditions for humans who are indoors. The uncomfortable thermal conditions can also be caused by the building itself due to the materials used for construction. Currently, many studies have been reported on building materials that can be used in passive methods for achieving energy efficiency and thermal comfort (Latha et al., 2015).

Thermal Energy Storage

(TES) has been widely used to address fluctuations in energy demand and supply

gaps. There are three forms of TES: Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage (LHTES),

Sensible Heat Thermal Energy Storage (SHTES), and thermochemical storage

systems (Nomura et al., 2015). Phase Change

Materials (PCM) are TES materials currently in great demand by researchers

owing to their large thermal energy storage capacity during the charging and

discharging processes (Jamekhorshid et al., 2014). The correct use of

PCM in the building can minimize peak cooling loads, allow the use of smaller

HVAC technical equipment for cooling, and maintain the indoor temperature

within a comfortable range owing to smaller indoor temperature fluctuations (Souayfane et al., 2016). Many studies have

been related to the application of PCM, especially in buildings. (Zhang et

al., 2017) used PCM

composites as a substitute for sand, (Laaouatni

et al., 2016) used PCM

to build optimal walls made of concrete blocks filled with PCM and ventilated

tubes, and (Saikia et al., 2018) incorporated PCM

into concrete walls to reduce the increase in heat and temperature fluctuations

in the buildings.

PCM are grouped into three

types: organic, inorganic, and eutectic (Kant et al., 2016). Fatty acids as

organic PCM have several advantages. It has a large storage capacity, abundant

in nature, non-toxic, not harmful to health, non-corrosive, and exhibits low

supercooling (Rasta and Suamir, 2018). However, organic

PCM has low conductivity and the possibility of leakage during the phase-change

process (Huang et al., 2017). The stabilized form

of PCM is used to eliminate losses and increase the PCM efficiency in terms of

thermal and physical properties. The

incorporation of nanomaterials into pure PCM can significantly increase their

thermal conductivity and stability (Kalaiselvam

and Parameshwaran, 2014). Many

researchers have carried out mixing PCM with nanomaterials. In a study by (Amin et al., 2017), beeswax PCM was mixed with graphene

nanoparticles; (Meng et

al., 2013)

synthesized a fatty acid/CNT composite, (Wi et al., 2015) studied

shape-stabilized phase change materials using fatty acid esters and exfoliated

graphite nanoplatelets, and (Kim et al., 2016) synthesized

octadecane/expanded graphite composites. Thus, several studies have been

conducted to enhance nano-PCM's material stability and thermal conductivity.

Graphene is the world’s

thinnest material—a single layer of carbon atoms that has excellent electrical

properties graphene can make it play a large role in energy storage, material

composites, sensors, and other fields. The structure of graphene, consisting of

layers, makes graphene highly conductive with carrying mobility of up to

200,000 cm2V-1 s -1 and thermal conductivity

of up to 5,300 Wm-1K -1

(Kusrini et al., 2019). The new

two-dimensional material, MAXene, has hydrophilic properties, excellent

oxidation resistance, high thermal and electrical conductivity, high thermal

stability, and high surface area (Naguib

et al., 2012).

Appropriate shape stabilization methods are required to achieve the desired

modifications in the thermal stability of materials using nanoparticles. The

shape-stabilized PCM (SSPCM) method is divided into three: mixing,

ultra-sonification, and impregnation (Lee et

al., 2018). Mixing is one of the simplest, but there is

no stable connection or bond between the PCM and the supporting material.

Ultra-sonification is a method performed by injecting a PCM into the pores of

the supporting material (Kusrini et al, 2019). Impregnation is a method that removes gas and moisture from pores and

then injects them with the PCM (Putra et al., 2019). The discovery and identification of PCM properties are very important

because PCM has several benefits and applications that can solve energy

problems. In this study, the organic properties of a PCM were modified to

improve its thermal properties. The organic PCM selected in this study was

derived from a group of waxes, namely soy wax, because it has a temperature

range close to room temperature, so it has the potential to be applied on a

wide scale. Based on its application as a heat energy storage material in

buildings subjected to repeated heating and cooling cycles, it is very

important to know the durability of a PCM. In a study conducted by (Trisnadewi et al., 2021), pure soy wax

thermal cycle test results were obtained. Thermal cycling

tests were performed with heating and cooling cycles of 0, 500, 1000, 3000, and

5000. Soy wax experienced an increase in melting and solidification

temperatures with a percentage increase, Tm_soywax 9%, and Ts_soywax

13%, respectively, after testing up to 5000 cycles, which represented the

application of the PCM for approximately 13 years. Soy wax was synthesized with

nanoparticles, such as graphene and MAXene, to increase the effectiveness of

soy wax as a TES material by increasing thermal conductivity.

2.1. Sample Preparation

Soy wax has a melting point of 43.92°C

with a latent heat of 117.59 J/g and a solidification point of 38.49 °C with a

latent heat of 122.18 J/g (Trisnadewi et al., 2021). This

PCM material was synthesized with graphene nanoparticles in the form of a black

powder purchased from XFNANO-China type XFQ021. It had an electrical

conductivity of 800–1100 S/cm, an apparent density of 0.09–0.13 g/cm3,

and a tap density of 0.13–0.16 g/cm3. Another nanoparticle sample,

MAXene Ti3AlC2, was purchased from 2D Semiconductors

(USA). In general, a MAX phase is initially formed by the formula Mn+1AXn,

where n = 1, 2, or 3. M is an early transition metal, A is a group of 13 or 14

elements, and X is either carbon or nitrogen (Barsoum, 2000).

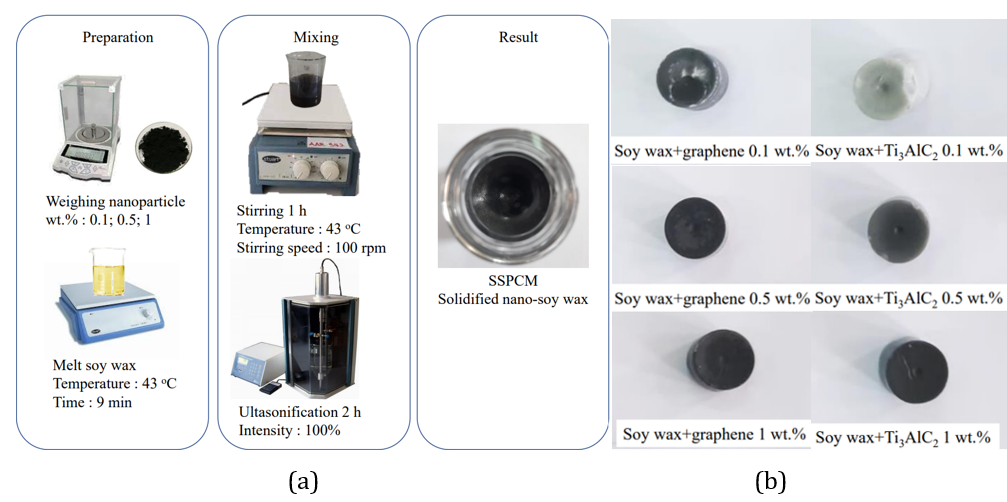

The mixing and

ultra-sonification were used to synthesize soy wax with nanoparticles. The

synthesis processes of soy wax+graphene and soy wax+MAXene are shown in Figure

1 (a), and the synthesis result is shown in Figure 1 (b). The first step

involved weighing the mass of nanoparticles using Fujitsu FSR-A320 and soy wax with

three percentage variations, 0.1, 0.5, and 1 wt.%, referring to Equation (1).

Then, soy wax was melted until it was in liquid form using Stuart CB162. In the

third step, the weighed nanoparticles were placed in a beaker, and the soy wax

liquid was poured. The fourth step involved mixing and the synthesis was

carried out using a magnetic stirrer for 1 h with stable heating during a

stirring speed of 100 rpm, followed by ultra-sonification for 2 h using a 20

kHz 950 W ultrasonic processor.

Figure 1 Nano-PCM

synthesis process (a), Synthesis of soy wax+graphene & soy wax+Ti3AlC2 (b)

2.2.

Characterization and property testing method

The characterization of composite

nano-PCMs is important for understanding the impact of nanoparticles. The

nature of the functional groups, their interactions with the molecular

architecture of the support matrix in the composite, and other chemical

properties of the nano-PCM were confirmed using an FT-IR Nicolet™ iS50. The

material's physical properties were characterized using SEM-EDS to determine

the mixed specimens' topography, morphology, composition, crystallography, and

elemental composition. In this test,

SEM-EDS was used with a voltage of 20 kV and a resolution of 512 × 384 pixels. The

instrument used to measure the thermal conductivity of the nano-PCM was a

C-Therm TCI thermal conductivity analyzer with a testing range of 0–100 W/mK.

The modified transient plane source (MTPS)-ASTM D7984 measurement method was

used with a test temperature range of -50–200oC, time testing range

0.8–3 s, precision better than 1%, and accuracy better than 5%. The DSC method

was used to measure the thermal energy storage behavior of the PCM and

composites, including the melting temperature (Tm), solidification

temperature (Tf), latent heat of melting (Hm), and

latent heat of solidification (

Hf). The DSC

(ASTM F 2625-10) measurements were conducted at 5 °C/min heating and

cooling rates and in the temperature ranges of 10–120°C and 120–10°C and were

held for 5 min at 120°C in air.

The chemical structure of PCM composites was analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy. Figure 2 shows the peaks for pure soy wax (a), soy wax adding graphene (b), and Ti3AlC2 (c) with various mass percentages. Pure soy wax has an absorption peak of 2848-2955 cm-1 which indicates the presence of strain vibrations (C-H) of alkanes (Trisnadewi et al., 2021). The absorption peak of soy wax is at 2916 cm-1, which indicates the strong strain frequency of the CH3, CH2, and C-H functional groups (Pethurajan et al., 2018). Soy wax has an absorption peak in 1702–1738 cm-1, which indicates the absorption of the strain vibration of the carboxylate group (C=O). After synthesizing the spectra of the PCM samples, soy wax+graphene (Figure 2(b)) and soy wax+ Ti3AlC2 (Figure 2(c)) show similar peak spectra to those of pure soy wax. The transmittance value decreases with an increase in the weight of the nanoparticles. This decrease indicates a decrease in the percentage of functional groups in soy wax owing to the addition of nanoparticles. This also shows an increase in the presence of nanoparticles in the mixture as the resulting transmittance value decreases. Based on the FTIR results, the addition of graphene and MAXene does not produce any new peaks. These results indicate no chemical interaction between soy wax and graphene or MAXene after the synthesis process.

Figure 2 FTIR spectra of pure

soy wax (a), soy wax + graphene (b), soy wax + Ti3AlC2 (c)

The

morphology of the nano-PCM mixture was analyzed using SEM-EDS. Figure 3 (a)

shows the SEM images of the mixture of soy wax and graphene nanoparticles at a

magnification of 5 µm. The morphology is multilayer or stack-like. There are

lumps, the texture is not very rough, and the corners of the graphene sheet are

not very sharp. Figure 4 (a) shows the results of the SEM test of the mixture

of soy wax and Ti3AlC2 at a magnification of 5 µm. When

compared with graphene, Ti3AlC2 has a wider and more

structured sheet. The texture shown in the Ti3AlC2 SEM

results is almost the same as that of graphene, i.e. sheets with angles that

are not too sharp. The difference is that the particle size of graphene is

smaller than that of Ti3AlC2 . Thus, when viewed from the

perspective of particle size, it can be observed that the thermal conductivity

of the mixture of soy wax and graphene is greater. The multi-layered morphology

of graphene and MAXene allows more nanoparticles to be adsorbed onto the

surface of soy wax. When more nanoparticles are adsorbed, the stability of the

soy-wax material is greater.

Figures 3 (b) and 4 (b) show the results of the EDS mapping test, which aimed to determine the elements that constituted the mixture. Both EDS mapping results show that these two mixtures have very high C (carbon) content. In addition to similarities in element C, these two materials contain O. The EDS results of these two samples follow the results of the FTIR test, which shows the presence of hydrocarbon bonds. The difference between these two samples is the Al content of Ti3AlC2 . Figure 4 (b) shows aluminum scattered along the carbon sheet. The presence of carbon and aluminum in PCM soy wax can increase the thermal conductivity of the material, increasing the ability of PCM soy wax to conduct heat. Based on the EDS test, the carbon value of MAXene can approach the carbon content in graphene, namely 82.2 wt.% in Ti3AlC2 and 84.49 wt.% in graphene. These results indicate that MAXene Ti3AlC2 is feasible and has excellent potential for use as a supporting material with characteristics like those of graphene.

Figure 3 (a). Morphology of a mixture of soy wax and graphene nanoparticles; (b) mapping distribution elements of graphene

Figure 4 (a). Morphology of a mixture of soy wax and Ti3AlC2 nanoparticles; (b) mapping distribution elements of Ti3AlC2

Thermal

conductivity testing was carried out at a temperature of approximately 20oC,

and data collection was repeated 10 times to obtain accurate results. The

average thermal conductivity test results are shown in Table 1. Figure 5 (a)

shows the ratio of the increase in the average thermal conductivity of soy wax

after synthesis with graphene and Ti3AlC2. Soy

wax+graphene results in an increase of 5% at a mass percentage of 0.5 wt.% with

a ratio of 6.01 with pure soy wax. Soy wax+ Ti3AlC2 results in an increase of 4.7% at a mass percentage of 1 wt.% with a ratio of

5.71 with pure soy wax. The results show an increase in thermal conductivity

with an increase in the weight of the nanoparticles (Putra et al., 2016).

However, a mixture must have an optimal point such that in the event of

exceeding the optimum limit, there is no change or deterioration in properties.

This condition occurs in the soy wax and graphene mixture, with a decrease of

0.01 W/mK at 1 wt.%.

The addition of a particular mass

fraction of nanoparticles to the PCM results in a decrease in the melting

point, solidification point, and latent heat of the PCM (Huang et al., 2017). The graph for the

soy wax and graphene mixture shows the same trend for the three mass

variations, namely, heat flow degradation and changes in melting point and

solidification point, and the same trends are observed for soy wax + Ti3AlC2.

Figure 5(b) shows the effect of the nanoparticles on the melting and

solidification rates. This demonstrates that the melting temperature of the nano-PCM

slowly decreases, but the solidification rate does not change significantly

with the addition of nanoparticles. The mixture of soy wax + graphene

experiences an increase in melting point concerning that of pure soy wax by 6.4oC

and by 5.5oC for the solidification point, with a constant value for

each increase in the percentage of graphene. For soy wax + Ti3AlC2,

the melting point is increased by 7.4oC, but the solidifying point

reduces by 5.3oC from that of pure soy wax. Based on the results of

these thermal properties, it is evident that the addition of nanoparticles

enhances thermal conductivity but reduces its melting point. The thermal

properties and enthalpy of the PCM were investigated using a DSC test. The test

results are shown in Figure 6, in which the graphs are generated using dynamic

mode (Barreneche et al., 2013). The enthalpy value

based on the DSC result is representative of the peak area, but this result

shows the data with

In

contrast to the solidification peak area, the soy wax + graphene mixture

decreased after the wt% of 0.5 wt% by 560.1 µVs/mg but increased after 1 wt% to

585.9, but in the soy wax + Ti3AlC2 mixture, there was a

linear decrease. From the values of thermal conductivity, melting, and

solidification temperatures, the melting and solidification peak areas show the

same pattern where at 0.5 wt% there is a decrease and a non-linear increase

with an increase in the proportion of the amount. Thus, it can be solved that

the concentration of 0.5 wt% graphene+soy wax mixture is the maximum/best

mixture to increase the thermal properties of soy wax.

Figure 5 (a) The enhancement percentage of thermal conductivity of soy wax + graphene and soy wax + Ti3AlC2, (b) Effect of nanoparticles on melting and solidification temperatures of nano-PCMs

Figure 6 DSC curves of (a)

pure soy wax, (b) soy wax + graphene, (c) soy wax +

Table 1 Thermal

properties of soy wax + graphene and soy wax +

Synthesis of soy wax with nanoparticles

using the stirring and ultra-sonification methods does not change the chemical

structure of soy wax, which is composed of fatty acids. The morphology of

graphene and MAXene Ti3AlC2 is a layered sheet, which

allows the soy wax to bind and trap more nanoparticles. The highest thermal

conductivity value of 0.89 W/mK was obtained for soy wax-graphene of 0.5 wt.%

and 0.85 W/mK for soy wax-Ti3AlC2 of 1 wt.%. The soy wax

and graphene mixture showed the same tendency as the soy wax + Ti3AlC2 synthesis in heat flow degradation and changes in melting and freezing points.

The soy wax + graphene mixture increases the melting point of pure soy wax by

6.4oC and the solidification point increases by 5.5oC for

each increase in the percentage of graphene. The melting point for soy wax + Ti3AlC2 increases by 7.4oC, but the solidification point decreases by 5.3oC

from pure soy wax. This study concludes that soy wax modified with graphene and

MAXene can improve the properties and thermal conductivity of the material and

increase the stability of the soy wax material when it undergoes a phase change

process. The best percentage of graphene+soy wax is 0.5 wt%, with the highest

thermal conductivity with stable thermal properties.

Al-Obaidi, K.M., Ismail, M., Rahman, A.M.A. 2014. Passive Cooling Techniques Through Reflective And Radiative Roofs In Tropical Houses In Southeast Asia: A Literature Review. Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 3(3), pp. 283–297

Amin, M., Putra, N., Kosasih, E.A., Prawiro, E., Luanto, R.A., Mahlia, T.M.I., 2017. Thermal Properties Of Beeswax/Graphene Phase Change Material As Energy Storage For Building Applications. Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 112, pp. 273–280

Barreneche, C., Solé, A., Miró, L., Martorell, I., Fernández, A.I., Cabeza, L.F. 2013. Study On Differential Scanning Calorimetry Analysis With Two Operation Modes And Organic And Inorganic Phase Change Material (PCM). Thermochimica Acta, Volume 553, pp. 23–26

Barsoum, M.W. 2000. The MN+1AXN Phases: A New Class Of Solids: Thermodynamically Stable Nanolaminates. Progress in Solid State Chemistry, Volume 28, pp. 201–281

Huang, X., Alva, G., Liu, L., Fang, G., 2017. Preparation, Characterization And Thermal Properties Of Fatty Acid Eutectics/Bentonite/Expanded Graphite Composites As Novel Form–Stable Thermal Energy Storage Materials. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Volume 166, pp. 157–166

Imessad, K., Derradji, L., Messaoudene, N.A., Mokhtari, F., Chenak, A., Kharchi, R., 2014. Impact Of Passive Cooling Techniques on Energy Demand For Residential Buildings In A Mediterranean Climate. Renewable Energy, Volume 71, pp. 589–597

Jamekhorshid, A., Sadrameli, S.M., Farid, M., 2014. A Review Of Microencapsulation Methods Of Phase Change Materials (PCMs) as a Thermal Energy Storage (TES) Medium. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 31, pp. 531–542

Kalaiselvam, S., Parameshwaran, R., 2014. Thermal Energy Storage Technologies For Sustainability: Systems Design, Assessment and Applications. Boston: Academic Press.

Kant, K., Shukla, A., Sharma, A., Kumar, A., Jain, A., 2016. Thermal Energy Storage Based Solar Drying Systems: A Review. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, Volume 34, pp. 86–99

Kim, D., Jung, J., Kim, Y., Lee, M., Seo, J., Khan, S.B., 2016. Structure And Thermal Properties Of Octadecane/Expanded Graphite Composites as Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Materials. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Volume 95, pp. 735–741

Kusrini, E., Putra, N., Siswahyu, A., Tristatini, D., Prihandini, W.W., Alhamid, M.I., Yulizar, Y., Usman, A., 2019. Effects of Sequence Preparation of Titanium Dioxide–Water Nanofluid Using Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide Surfactant and TiO2 Nanoparticles for Enhancement of Thermal Conductivity. International Journal of Technology, Volume 10(7), pp. 1453-1464

Laaouatni, A., Martaj, N., Bennacer, R., Elomari, M., El Ganaoui, M., 2016. Study of Improving The Thermal Response of a Construction Material Containing a Phase Change Material. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Volume 745, p. 032131

Latha, P.K., Darshana, Y., Venugopal, V., 2015. Role of Building Material In Thermal Comfort In Tropical Climates – A Review. Journal of Building Engineering, Volume 3, pp. 104-113

Lee, J., Wi, S., Yun, B.Y., Chang, S.J., Kim, S., 2019. Thermal and Characteristic Analysis Of Shape-Stabilization Phase Change Materials By Advanced Vacuum Impregnation Method Using Carbon-Based Materials. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Volume 70, pp. 281–289

Meng, X., Zhang, H., Sun, L., Xu, F., Jiao, Q., Zhao, Z., Zhang, J., Zhou, H., Yutaka, S., Liu, Y., 2013. Preparation and Thermal Properties of Fatty Acids/CNTs Composite As Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Materials. Journal of thermal analysis and calorimetry, Volume 111, pp. 377–384

Naguib, M., Come, J., Dyatkin, B., Presser, V., Taberna, P.L., Simon, P., Barsoum, M.W., Gogotsi, Y., 2012. MXene: a Promising Transition Metal Carbide Anode For Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochemistry Communications, Volume 16, pp. 61–64

Nomura, T., Zhu, C., Sheng, N., Tabuchi, K., Sagara, A., Akiyama, T., 2015. Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Composite By Impregnation Of Octadecane Into Mesoporous Sio2. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Volume 143, pp. 424–429

Pethurajan, V., Sivan, S., Konatt, A.J., 2018. Facile Approach To Improve Solar Thermal Energy Storage Efficiency Using Encapsulated Sugar Alcohol Based Phase Change Material. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Volume 185, pp.524–535

Putra, N., Prawiro, E., Amin, M., 2016. Thermal Properties of Beeswax/CuO Nano Phase-change Material Used for Thermal Energy Storage. International Journal of Technology, Volume 7(2), p. 244–253

Putra, N., Rawi, S., Amin, M., Kusrini, E., Kosasih, E.A., Mahlia, T.M.I., 2019. Preparation Of Beeswax/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes As Novel Shape-Stable Nanocomposite Phase-Change Material For Thermal Energy Storage. Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 21, pp. 32–39

Rasta, I.M., Suamir, I.N., 2018. The Role of Vegetable Oil In Water Based Phase Change Materials for Medium Temperature Refrigeration. Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 15, pp. 368–378

Saikia, P., Azad, A., Rakshit, D., 2018. Thermodynamic Analysis Of Directionally Influenced Phase Change Material Embedded Building Walls. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, Volume 126, pp. 105–117

Souayfane, F., Fardoun, F., Biwole, P.H., 2016. Phase Change Materials (PCM) for Cooling Applications in Buildings: A Review. Energy and Buildings, Volume 129, pp. 396–431

Trisnadewi, T., Kusrini, E., Nurjaya, D.M., Putra, N., Mahlia, T.M.I., 2021. Experimental Analysis Of Natural Wax As Phase Change Material By Thermal Cycling Test Using Thermoelectric System. Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 40, p. 102703

Vennapusa, J.R., Konala, A., Dixit, P., Chattopadhyay, S., 2020. Caprylic Acid Based PCM Composite With Potential for Thermal Buffering and Packaging Applications. Materials Chemistry and Physics, Volume 253, p. 123453

Wi, S., Seo, J., Jeong, S.G., Chang, S.J., Kang, Y., Kim, S., 2015. Thermal Properties of Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Materials Using Fatty Acid Ester and Exfoliated Graphite Nanoplatelets For Saving Energy in Buildings. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Volume 143, pp. 168–173

Zhang, L., Yang, W., Jiang, Z., He, F., Zhang, K., Fan, J., Wu, J., 2017. Graphene Oxide-Modified Microencapsulated Phase Change Materials with High Encapsulation Capacity and Enhanced Leakage-Prevention Performance. Applied Energy, Volume 197, pp. 354–363