Catalytic Cracking Column Scheme Modernization for Efficient Utilization of Thermal Energy

Corresponding email: tspa_kgeu@mail.ru

Published at : 28 Jul 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 5 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i5.5560

Valerievich, F.A., Igorevna, B.M., Ivanovich, S.V., Evgenievich, S.A., Sergeevna, D.E., Gareevna, A.I., 2023. Catalytic Cracking Column Scheme Modernization for Efficient Utilization of Thermal Energy. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(5), pp. 1103-1112

| Fedyukhin Alexander Valerievich | National Research University “Moscow Power Engineering Institute”, Russian Federation, 111250, Moscow, Krasnokazarmennaya st., 14 |

| Boltysheva Margarita Igorevna | National Research University “Moscow Power Engineering Institute”, Russian Federation, 111250, Moscow, Krasnokazarmennaya st., 14 |

| Sitas Viktor Ivanovich | National Research University “Moscow Power Engineering Institute”, Russian Federation, 111250, Moscow, Krasnokazarmennaya st., 14 |

| Savostikov Artem Evgenievich | National Research University “Moscow Power Engineering Institute”, Russian Federation, 111250, Moscow, Krasnokazarmennaya st., 14 |

| Dremicheva Elena Sergeevna | Kazan State Power Engineering University, Russian Federation, 420066, Kazan, Krasnoselskaya st., 51 |

| Akhmetova Irina Gareevna | Kazan State Power Engineering University, Russian Federation, 420066, Kazan, Krasnoselskaya st., 51 |

This paper aims to analyze options for the

utilization of waste heat at oil refineries, specifically focusing on the

rectification column. The study was carried out using the Aspen HYSYS software

package. In this paper, two fundamentally different solutions were considered,

which were modeled in the Aspen HYSYS software package, the proposed options

were also compared, and their advantages and disadvantages were identified. In

the first case, it is proposed to consider using the energy from the

hydrocarbon stream to heat water for a hot water supply system. In the second

case, it is proposed to use same initial energy stream to produce electricity

by applying Rankine cycle. As a result of the study, both proposed options for

waste heat utilization were recognized as economically justified. However, the

feasibility of using these solutions depends significantly on the needs of a

particular enterprise, on their scale, the schemes implemented on them, the

operating installations composition, loads, energy consumption parameters, and

other parameters.

Aspen HYSYS; District heating; Oil refining; Organic rankine cycle; Thermal energy utilization

In Russia, which ranks as the second-largest oil producer globally and the third-largest in terms of processing capacity, with over 30 oil refineries across its territory, the energy efficiency level in this industry falls below the global leaders. Therefore, it is expedient to improve technologies, upgrade and modernize equipment, as well as to introduce methods for utilizing the various hot streams heat of oil refineries (Li et al., 2021). The largest oil refining companies in Russia are trying to improve the energy efficiency of the refining sector in various ways. The main energy and resource-saving directions at oil refineries include the following methods: carrying out organizational and technical measures to reduce the energy capacity of process units, the old equipment modernization and replacement with new one with higher efficiency; fuel use of technologies optimization; an increase in heat recovery by optimizing the coolant flow patterns, as well as by increasing the recuperators heat exchange area (Balzamov et al., 2020; Kusumah et al., 2019). Additionally, employing energy-efficient lighting devices, maximizing the utilization of unclaimed thermal energy, and improving its overall efficiency are key considerations (Mirkin et al., 2013; Glebova, Glebov, and Sazhina, 2005). This has become especially important as part of the new climate agenda aimed at reducing the carbon footprint (Newell and Simms, 2020). In addition, the main energy-saving principles also include an economic feasibility assessment of using any energy-saving technologies and solutions (Glagoleva and Piskunov, 2021).

Oil refineries strive to

enhance not only the energy efficiency level but also the depth of oil refining

while maximizing the yield of gasoline, kerosene, and diesel fuel (Rossi et

al., 2020). Obviously, with an increase in the depth of oil refining,

the number of technological processes and installations required to obtain

motor fuels of the appropriate quality also increases, which requires

significant capital investments. An increase in the depth of oil refining leads

to an increase in the various energy resources consumption amount, such as

high-pressure water vapor, electrical energy, as well as various types of fuel

(mainly natural gas) (Mirkin et al., 2014).

The production process of

the oil refining marketable products includes three stages: primary oil

processing (oil desalting and dehydration, its separation into fractions);

secondary oil processing (fractions obtained at the primary processing stage

take part in chemical reactions and are subject to subsequent fractionation);

commodity production (there is a mixing of various fractions with additives in

order to obtain commercial products with certain properties) (Akhmetov

et al., 2006).

At the primary processing

stage, crude oil is introduced into raw tanks, where it undergoes a settling

process to partially remove water and mechanical impurities. To facilitate oil

dehydration and desalting, emulsifiers are added to the oil, which is then

heated to temperatures ranging from 70 to 130 °C and subjected to an

alternating electric field. These processes take place in electric dehydrators,

where the pressure can reach up to 12 atm, and the alternating voltage value of

2 kV is applied (Bagdasarov, 2017; Podvintsev, 2011). Further, the crude oil is fed to the oil distillation column. In tube

furnaces, for which the fuel is purchased natural gas or hydrocarbon gas and

fuel oil produced at an oil refinery, oil is heated to a temperature of not

more than 360°C and fed into a distillation column, into which water vapor

enters (Wahid

and Ahmad, 2016). The liquid in the lower column part enters the reboiler,

where it is heated and partially vaporized, while the vapors move from bottom

to top, passing through layers of liquid, which flows from top to bottom from

one plate to another through overflow devices. Pressure and temperature

decrease with column height. Straight-run fuel oil is removed from the bottom

of the atmospheric distillation column cube, which is subjected to further

processing in a vacuum distillation column. In some cases, to reduce the load

on the main distillation column, a pre-topping oil column is installed. The raw

material entering this column is heated in the heat exchangers system due to

the hot flows of the main distillation column. Secondary oil processing

includes many technological processes and installations, the composition of

which may vary from refinery to refinery (Herzog, 2015). It should also be noted that the global trend in oil refining involves a

steady increase in the depth of oil refining, which leads to a significant drop

in the amount of bituminous raw materials, its shortage, and a decrease in the

heavy oil fractions quality (Karpov et al., 2021).

Oil refining processes

require the consumption of various types of energy resources, and oil refining

intermediate products often need to be cooled and condensed. In many oil

refineries, secondary energy resources are reused. However, this approach is

primarily applicable to hot streams with high-temperature potential,

particularly side streams and bottoms from oil distillation columns. As for the

rectification products in the gaseous state, the temperature of which is

relatively low and does not exceed 150°C, they are cooled and condensed in air

and water coolers, for which energy is expended. A significant amount of waste

heat energy from oil refineries is discharged into the environment instead of

being reused profitably. In this regard, the possibility of reusing this heat,

as well as the feasibility of such a solution, is being considered.

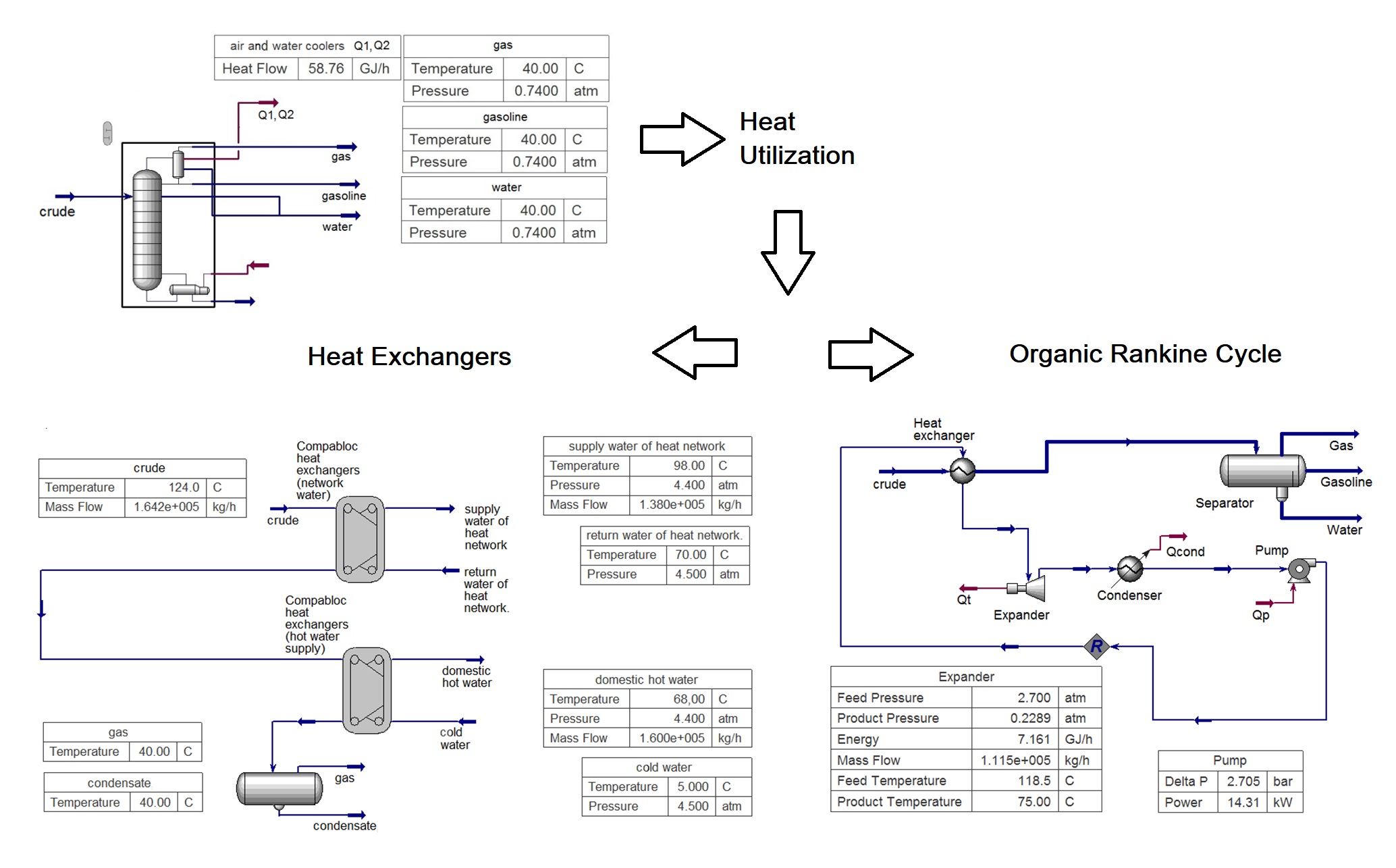

The article considers the

process of cooling the raw material coming from the top of the column of the

catalytic installation. During the study, a catalytic cracking distillation

column with air coolers and water coolers was simulated to determine the

emitted heat. It was assumed that the heat removed from the plant could be used

to produce steam for technological needs, heat buildings, and generate

electricity. After collecting the initial data on the selected installation, we

simulated the processes of heating water with the heat of oil products in heat

exchangers in order to determine what temperature the heated water would be and

what its mass flow would be. Single-stage and two-stage water heating schemes

were considered. We also simulated the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) with two

configurations. In one case, we include the ORC scheme with a regenerative

heater, while in the other case, the regenerative heater was not included in

the scheme. These two models made it possible to determine how much electrical

energy can be generated by utilizing the heat of oil products from the top of

the catalytic cracking column.

The selection of the working

fluid is not a primary focus in this study, as ORC equipment suppliers

typically determine the appropriate working fluid themselves. This study presents

new opportunities for resource conservation and environmental improvement

through heat recovery from moderately hot streams, specifically in the context

of oil refineries. If the feasibility of implementing the proposed solutions is

confirmed, consideration of this problem can be very useful since the found

methods of waste heat utilization can be applied to existing enterprises.

2.1. Initial

data

This

article discusses options for thermal energy utilization, which must be removed

from the overhead of a catalytic cracking oil distillation column. The raw

material obtained in the catalytic cracking process enters the distillation

column. Heavy catalytic-cracking gas oil is removed from the column bottom,

part of which is heated in a reboiler and returned back to the column. The

overhead vapors of the column with a temperature of 125°C and a pressure of 0.1

MPa first enter the air coolers, where their temperature is reduced to 60°C,

and then the vapor is fed to water coolers, where the temperature is reduced to

40°C. The resulting vapor-liquid mixture is separated in the separator into

gas, condensate, and water. The separator pressure is 0.074 MPa, and the

temperature is 40°C.

Since the purpose of the

study is to find practical solutions, the initial data was provided by one of

the operating oil refineries. The catalytic cracking unit was commissioned at

JSC TANECO in 2021. It is capable of processing over 1 million tons of crude

oil annually into a Euro 6 high-octane gasoline component. Also, the catalytic

cracking unit products are light gas oil (raw material for EURO 6 diesel fuel)

and liquefied hydrocarbon gases (propane-propylene and butane-butylene

fractions) (Tatneft, 2021).

2.2. Determining

the amount of heat removed

To determine the heat

removal in air coolers and water coolers, an oil distillation column model was

created using the Aspen HYSYS software package. The process of creating a

mathematical model in the Aspen HYSYS software package includes the following

main steps: specifying the chemicals involved in the simulated processes; the

selection of thermodynamic mode, on the basis of which calculations will be

performed; mathematical modeling, which includes the assignment of material,

energy flows, technological installations; debugging the mathematical model and

finding the optimal solution.

The Peng-Robinson

equation-solving package was chosen for mathematical simulation. This equation

is used to describe the phase transformations of oil and gas mixtures (Faizov, 2019). In the created mathematical model (Figure 1),

the condenser simultaneously performs the functions of air coolers, water

coolers and a separator. To

further refine the obtained results, separate models were created for the

coolers and separator, independent of the oil distillation column.

Figure 1 Column model with the

condenser, which simultaneously performs the functions of air coolers, water

coolers, and a separator.

2.2. Thermal energy utilization methods

2.2.1.

Schemes with the use of heat exchangers for water heating

Oil refineries usually

have their own boiler houses, in which network water is heated, and water vapor

is obtained. Part of the steam is produced in waste heat boilers. In order to

utilize waste heat and to increase the plant's performance, it is proposed to

heat make-up water entering the steam boilers. This solution has already been

implemented by Alfa Laval company at an oil refinery in the Canadian city of

Sarnia, where Compabloc heat exchangers were installed as condensers in the oil

distillation column of the catalytic cracking unit.

An alternative to this

solution is the heating of water intended for a hot water supply system. Due to

the large number of personnel working at the oil refinery, this enterprise has

a large hot water demand. In accordance with Sanitary rules and norms, the

water temperature for heat supply systems must be at least 60°C and not more

than 75°C (Sanitary Rules and Norms, 2021). The heat supply systems water at oil refineries is

usually used not only for heating purposes, but it is also used for heating

tanks with oil, fuel oil, and diesel fuel, and other needs (Mirkin et al., 2014). In the

variant under consideration, it is proposed to use a two-stage water heating

scheme.

2.2.2. Technological schemes using the organic

Rankine cycle

Currently,

Rankine organic cycle installations are being implemented to generate

electricity by utilizing low-grade heat extracted from various technological

installations. The peculiarity of this cycle is that the working fluid in the

turbine is not water vapor, as in conventional steam turbine plants, but an

organic high-molecular substance, the boiling point of which is lower than the

water boiling point. Therefore, the organic Rankine cycle can use low-potential

energy sources. Rankine organic cycle installations can use heat in the

temperature range from 90 to 400°C (Solomin, Daminov, and

Kamalov, 2020; Riyanto and Martowibowo, 2015).

The working fluid is

pumped to the evaporator, where it is vaporized and superheated. The

pressurized steam is then fed into the turbine, where it expands, performing

work. The exhaust steam is cooled and condensed, the condensate enters the

pump, and the cycle is closed (Muslim et al., 2019). A regenerative heat exchanger is often used in

Rankine organic cycle installations. In this case, the steam transfers part of

the heat to the cold working fluid and then condenses. Such a technological

solution allows to increase in the heat recovery degree, as well as to increase

the cycle efficiency (Leonov et al., 2015).

Rankine organic cycle

installations are used in various waste heat recoveries systems, such as

geothermal power plants, exhaust gas heat recovery systems for gas turbine and

gas piston installations, systems using the heat of hot process gases, and

biomass power generation complexes. These installations are widespread in the

world, but in the Russian Federation, there are only some power plants

operating on the organic Rankine cycle, built in the middle of the 20th century

and still operating (Paratunskaya GeoTPP and Mutnovskaya GeoTPP) (Dmitrenko and Kolpakov, 2021).

Freons (HFC-134a,

HFC-245fa, OMTS), toluene, and Solkatherm (azeotropic solution) are the most

widely used in the organic Rankine cycle. It is also possible to use cyclic

hydrocarbons, for example, cyclopentane and cyclohexane, as well as butene,

isobutene, etc. In scientific papers (Scagnolatto, Cabezas-Gomez,

and Tibirica, 2021; Muslim et al., 2019; Artemenko, 2014; Wang

et al., 2013; Saleh et al., 2007), the issue of a working fluid selection, as well as the influence of

various factors on the cycle efficiency, has been studied in detail.

The paper considers two

options for organic Rankine cycle installations: with and without a

regenerative heat exchanger. Cyclohexane was chosen as the working fluid.

3.1. The amount

of heat removed from the catalytic cracking column overhead

As a result of a distillation column

mathematical modeling of a catalytic cracking unit, the amount of heat removed

by the column condenser was determined and amounted to 58.76 GJ/h. As a result

of modeling, the processes occurring in the coolers and the separator, separately

from the column (Figure 2), are consistent with the obtained value. Therefore,

the model was created correctly, and the results obtained are suitable for

further calculations.

Figure 2 Scheme of cooling and

condensation of the catalytic cracking column overhead vapors with their

further separation

3.2. Mathematical modeling results of water heating

schemes

With a thermal energy input

of 58.76 GJ/h, it is feasible to heat 180.8 t/h of chemically treated water

from 20°C to 95°C (Figure 3). The heated water, following deaeration, is then

directed to steam boilers for the production of superheated steam.

Figure 3 Model of chemically purified water heating using

Compabloc heat exchangers

When

we heat network water from 70 to 98°C and water for hot

water supply from 5 to 68°C, we obtain mass flow

rates of 138 and 160 t/h, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Water heating model of the hot water supply system and

network water using Compabloc heat exchangers

It should be noted that this amount of heat in excess covers

the needs of the refinery in hot water, so this solution is not optimal. The

need for heating the network water is seasonal. Consequently, the amount of

utilized heat will vary depending on the time of the year. During the warm

period, the load on air coolers will increase significantly, which will lead to

an increase in electricity consumption. We came to the conclusion that in this

case, it is preferable to use waste heat for the further process of steam

production rather than to heat water for district heating and hot water supply

system.

3.3. Mathematical

modeling results of technological schemes using the organic Rankine cycle

As noted above, the paper considers two

options for low-grade thermal energy utilization using the organic Rankine

cycle: with (Figure 4) and without the regenerative heat exchanger (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Organic Rankine cycle installation model with the

regenerative heat exchanger

Figure 6 Organic Rankine cycle installation model without the

regenerative heat exchanger

In some cases, the use of

the regenerative heat exchanger can significantly increase the cycle thermal

efficiency (Scagnolatto, Cabezas-Gomez,

and Tibirica, 2021). The

results obtained during mathematical modeling and further calculations are

shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Rankine organic cycle installation performance

characteristics

As shown

in Table 1, we can produce more than 1.5 MW of electrical energy with an

organic Rankine cycle installation. While this capacity may not cover all the energy needs of the oil

refinery, it is sufficient for further evaluation of the technical solution's

economic feasibility. The inclusion of a regenerative heat exchanger in the

organic Rankine cycle installation allows for an increase in the generated

electrical power. This reduces the heat load on the main heat exchangers and

reduces the installation size (Murgia et al., 2017). However, the results obtained indicate that in the

case under consideration, the inclusion of a regenerator in the circuit did not

lead to a significant increase in the cycle thermal efficiency 7.

The use of Compabloc heat

exchangers makes it possible to utilize the maximum amount of heat removed from

the catalytic cracking distillation column overhead. This technical solution

will make it possible to obtain an additional reserve of steam capacity, which

is important in terms of oil refinery performance increasing. It is not

effective to use waste heat for heating water for district heating and hot

water supply system. Moreover, the amount of heat in excess covers the needs of

the oil refinery in hot water, so this solution is inappropriate. A significant

disadvantage of organic Rankine cycle installation is the low efficiency. This

means that part of the recovered heat is still released into the environment

during the cooling of the working fluid in the condenser. However, this

installation also has a number of significant advantages: the possibility of

obtaining electricity from low-grade heat; the installation operates well at

partial load, high degree of automation and ease of maintenance; long service

life. At current price levels, installing Alfa Laval condensers will have a

shorter payback period than the introduction of the organic Rankine cycle

installation. At the same time, it should be noted that the organic Rankine

cycle installation is controlled by the manufacturer, who maintains the unit,

and, in this case, operating costs are taken into account. The heat exchange

equipment is serviced by the plant's workers, whose wages are not taken into

account in the calculation. The decision to build the Turboden organic Rankine

cycle installation will reduce the number of employees, resulting in additional

savings and a further decrease in the actual payback period. Despite all of the

above, the final decision should be made based on the need for the oil refinery

for a certain energy resource.

This research was funded

by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation

within the framework of the state assignment No. 075-03-2021-175/3 from

30.09.2021.

Akhmetov, S.A.,

Bayazitov M.I., Kuzeev I.R., Serikov T.P., 2006. Technology and Equipment

for Oil and Gas Refining Processes. 868th Edition. St

Petersburg: Nedra

Artemenko, S.V.,

2014. Fluorinated Ethers Working Bodies for Low-Temperature Rankine Cycle on

Organic Substances. Problems of Regional

Energy, Volume 3 (26), pp. 22–30

Bagdasarov, L.N.,

2017. Popular Oil Refining. Rusia: Russian State University of Oil and

Gas named after Gubkin

Balzamov, D.,

Akhmetova, I., Bronskaya, V., Kharitonova, O., Balzamova, E., 2020.

Optimization of Thermal Conditions of Heat Recovery Boilers with Regenerative

Heating in the High-Temperature Section of Isoamylene Dehydrogenation. International Journal of Technology.

Volume 11(8), pp. 1598-1607.

Dmitrenko,

A.V., Kolpakov, M.I., 2021. Analysis of the Issue of Recovery of Low-Potential

Energy at Small-Scale Energy Facilities. World

of Transport and Transportation. Volume 19(2), pp. 100–106

Faizov, A.R., 2019. Improvement

of Hardware Design of Fractionating Equipment and Separation Schemes for

Multicomponent Mixtures. Rusia: Ufa State Oil Technical University

Glagoleva,

O.F., Piskunov, I.V., 2021. Energy Saving is a Priority Task of Modern Oil and

Gas Processing. Business Magazine

NEFTEGAZ.RU, Volume 109(1), p. 32

Glebova, E.V.,

Glebov, L.S., Sazhina, N.N., 2005. Fundamentals Of Resource-Energy-Saving

Technologies of Hydrocarbon Raw Materials. 2nd Edition. Rusia: Oil

and Gas Publishing House of the Russian State University of Oil and Gas named

after Gubkin, p. 184

Herzog, U., 2015,

Technical and Economical Experiences with Large ORC Systems Using Industrial

Waste Heat Streams of Cement Plants, Holcim

Technology Ltd. Available Online at: https://www.hslu.ch/-/media/campus/common/files/dokumente/ta/ta-forschung/fmhm/orc-symposium-201

5/03-herzog.pdf?la=de-ch, Accessed on February 14, 2022

Karpov,

N.V., Vakhromov, N.N., Dutlov, E.V. Bubnov, M.A., Gudkevich, I.V., Gureev,

A.A., Borisanov, D.V., 2021. Development of Technology and Production

Characteristics for Deeply Oxidized Roofing Bitumen. Chemistry and Technology of Fuels and Oils, Volume 57, pp. 640–644

Kusumah, S.A.,

Hakim, I.I., Sukarno, R., Rachman, F.F., Putra, N., 2019. The Application of

U-shape Heat Pipe Heat Exchanger to Reduce Relative Humidity for Energy

Conservation in Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) Systems. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 10(6), pp. 1202–1210

Leonov, V.P., Voronov,

V.A., Apsit, K.A., Tsipun, A., 2015. Rankine Cycle with Low Potential Heat

Source. Engineering Journal: Science and

Innovations. Volume 2 (38), p. 12

Li, F., Qian, F., Du,

W., Yang, M., Long, J., Mahalec, V., 2021. Refinery Production Planning

Optimization Under Crude Oil Quality Uncertainty. Computers and Chemical Engineering. Volume 151, p. 107361

Mirkin, A.Z.,

Yaitskikh, G.S., Krasnov, A.V., Yaitskikh, V.G., 2013. Energy Saving at Oil

Refineries. Oil and Gas Journal Russia,

Volume 11 (77), pp. 72–75

Mirkin, A.Z.,

Yaitskikh, G.S., Sunyaeva, G.S., Yaitskikh, V.G., 2014. Reducing Energy

Consumption at Oil Refineries. Oil and Gas

Journal Russia. Volume 5 (83), pp. 40–43

Murgia, S., Valenti,

G., Colletta, D., Costanzo, I., Contaldi, G., 2017. Experimental Investigation

into an ORC-Based Low-Grade Energy Recovery System Equipped with Sliding-Vane

Expander Using Hot Oil from an Air Compressor as Thermal Source. Energy Procedia. Volume 129, pp. 339–346

Muslim, M., Alhamid,

M.I., Nasruddin, N., Yulianto, M., Marzuki, E., 2019. Cycle Tempo Power

Simulation of the Variations in Heat Source Temperatures for an Organic Rankine

Cycle Power Plant using R-134A Working Fluid. International Journal of Technology. Volume 10(5), pp. 979–987

Newell, P., Simms, A., 2020. Towards A Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. Climate policy, Volume 20(8), p. 1043–1054

Podvintsev, I.B.,

2011. Oil Refining. In: Practical Introductory Course: Study Guide.

Dolgoprudny, Rusia: Intellect Publishing House

Riyanto,

H., Martowibowo, S.Y., 2015. Optimization of Organic Rankine Cycle Waste Heat

Recovery for Power Generation in a Cement Plant via Response Surface

Methodology. International Journal of Technology. Volume 6(6), p. 938–945

Rossi, M., Comodi,

G., Piacente, N., Renzi, M. 2020. Energy Recovery in Oil Refineries by Means of

a Hydraulic Power Recovery Turbine (HPRT) Handling Viscous Liquids. Applied Energy. Volume 270, p. 115097

Saleh, B., Koglbauer,

G., Wendland, M., Fischer, J., 2007. Working Fluid for Low-temperature Organic

Rankine Cycle. Energy. Volume 32(7),

pp. 1210–1221.

Sanitary

Rules and Norms, 2021. Sanitary Rules and Norms (SanPiN) 2.1.3684-21. Russian

Federation, Rusia

Scagnolatto, G.,

Cabezas-Gomez, L., Tibirica, C.B., 2021. Analytical Model for Thermal

Efficiency of Organic Rankine Cycles, Considering Superheating, Heat Recovery,

Pump and Expander Efficiencies. Energy

Conversion and Management. Volume 246, p. 114628

Solomin,

I.N., Daminov, A.Z., Kamalov, R.F., 2020. Calculation Methods of The Gas Flow in

The Impeller of a Turbo-Expander of ORC Plant Used in The Heating Plant. Journal of Physics: Conference Series,

Volume 1565(1), p. 012073

Tatneft,

2021. Tatneft. Available online at: https://www.tatneft.ru/press-tsentr/press-relizi/more/8436/?lang=ru, Accessed on February 14, 2022

Wahid, A., Ahmad, A.,

2016. Improved Multi-model Predictive Control to Reject Very Large Disturbances

on a Distillation Column. International

Journal of Technology. Volume 7(6), pp. 962–971

Wang, D., Ling, X.,

Peng, H., Liu, L., Tao, L., 2013. Efficiency and Optimal Performance Evaluation

of Organic Rankine Cycle for Low Grade Waste Heat Power Generation. Energy. Volume 50, pp. 343–352