Ramie Fiber-Reinforced Polylactic-Acid Prepreg: Fabrication and Characterization of Unidirectional and Bidirectional Laminates

Corresponding email: tsoemardi@eng.ui.ac.id

Published at : 28 Jun 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 4 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i4.5940

Soemardi, T.P., Polit, O., Salsabila, F., Lololau, A., 2023. Ramie Fiber-Reinforced Polylactic-Acid Prepreg: Fabrication and Characterization of Unidirectional and Bidirectional Laminates. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(4), pp. 888-897

| Tresna Priyana Soemardi | Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

| Olivier Polit | Laboratoire Energétique Mécanique Electromagnétisme, Université Paris Nanterre, Ville d'Avray, 92410, France |

| Fanya Salsabila | Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

| Ardy Lololau | Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI Depok, 16424, Indonesia |

The fabrication of a natural prepreg with

poly-lactic acid (PLA) matrix and ramie fiber reinforcement was engineered on a

laboratory scale by impregnating the unidirectional and bidirectional ramie

fiber with PLA matrix solvent on a glass die. The obtained composite prepreg

has been stored at a very low temperature to maximize its shelf life. Tensile

and biodegradability tests of the composite laminates prepared by the

hot-pressing method have also been conducted. Tensile test results show that

the freezer-stored bidirectional 0/90° prepreg laminate specimen has the

highest tensile strength of 71.44 MPa with a modulus of 2.70 GPa on average. Meanwhile,

the unstored bidirectional 0/90° prepreg laminate specimen has the highest

level of elasticity, with a modulus of 1.29 GPa on average. The

biodegradability test shows the decomposition process of the composite laminate

under actual composting conditions. Microscopic observation of the damaged

specimen results shows good adhesion between the PLA matrix and ramie fiber and

the decomposition of the biodegradability test samples.

Composite; Natural prepreg; Polylactic Acid (PLA); Ramie fiber

Natural fiber-reinforced polymer (NFRP) has been a

trend in composite materials research and engineering (John et al., 2008). It offers the biodegradable advantages of a composite (Lotfi et al., 2019) and the comparable mechanical strength (Holbery and Houston, 2006) to the conventional synthetic ones (Faruk et al., 2012). Polylactic acid (PLA) is a biodegradable polymer that has become the

most pledging biodegradable material that has been used as a matrix in a

composite material due to its vulnerability to bacteria (Siakeng et al., 2019). It is frequently used to replace synthetic polymers to address the

disposal (environmental) problem (Alsaeed et al., 2013) we have faced in the recent decade. PLA is environmentally friendly and

can be decomposed naturally. PLA also had good physical and mechanical

properties (Bhardwaj and Mohanty, 2007). Furthermore, the usage of PLA as a matrix to natural fiber-reinforced

composite will bring out the maximum potential of fully biodegradable

composites.

On the other hand, ramie fiber has been used as reinforced in PLA composites due to its strength superiority among the stem fibers. Consequently, PLA and ramie fiber have been considered the most common natural constituents in biodegradable composite (Lololau et al., 2021) as a ramie fiber-reinforced polylactic-acid (RFRPLA).

Unfortunately, its composites still have to be

fabricated in conventional procedures. It can be improved by using a prepreg or

pre-impregnation during its preparation. Prepregs or pre-impregnated composites

are semi-finished composite products made by impregnating a textile/fabric

architecture of a fiber reinforcement with a thermoplastic or thermoset matrix

(resins). Therefore, a prepreg can be defined as a preform braided structure of

the reinforcement used as a composite (Potluri and Nawaz, 2011). Composite prepregs reduce the risk of poor impregnation quality by

ensuring that the amount of each constituent is correct and interacts well (Duhovic and Bhattacharyya, 2011). It will also reduce the risk of possible composite processing defects,

such as applying complex geometries like curvature indentations (Wang et al., 2020). Prepreg is generally used as a material for manufacturing components

in the aircraft industry because of its advantages: having a high track and

drape, which is useful for components with complex shapes (Seferis et al., 2011).

The reinforcing fiber in the prepreg will still be

aligned as it was before during the manufacturing process. Consequently, it is

considered suitable and capable of making parts with lower fiber defects with

excellent characteristics (Cairns et al., 2001). Prepreg has a very good performance compared to other forms of

composite materials. This material is suitable for manufacturing composite

parts that are very light but can bear significant loads (Wolff-Fabris et al., 2016). Prepregs require good storage, i.e., away from direct sunlight, heat,

and strong chemicals. To extend its shelf life, prepregs need to be stored at

temperatures below 0°C (Bhatnagar et al., 2006). The method of prepreg preparation on composites (especially

thermoplastics) with natural fiber reinforcement can be carried out by spinning

the reinforcing yarn with matrix filaments (Baghaei and Skrifvars, 2016; Baghaei et al., 2015; Baghaei et al., 2013). Another study also conducted the preparation by hot-rolling a matrix

sheet with reinforcing fabrics (McGregor et al., 2017). Preparation of prepregs can also be carried out by dissolving the

matrix granules into a solvent compound, which is then used to impregnate the

reinforcing fabrics (He et al., 2019).

Due to the gap from the predecessor studies, this

research had brought in the engineered fabrication of fully biodegradable

composite materials of ramie fiber as reinforcement and PLA as the matrix on a laboratory

scale by using a manual solvent casting impregnation method. Also, this

research aimed to determine the characteristic of its biodegradability,

interface bonding, and tensile properties.

2.1. Materials

Ramie plain-woven fabric was supplied by Guangzhou

Xinzhi Textile Co., Ltd. (China), and Bio-poly 103 PLA granules were chosen as

the matrix from Shanghai Huiang Industrial Co., Ltd. (China). Meanwhile, NaOH

and dichloromethane were supplied by a local distributor PT. Indogen Intertama

(Indonesia).

2.2. Prepreg preparation

Two types of reinforcement were fabricated: unidirectional and

bidirectional. The bidirectional will be prepared in 0/90° and ±45° fabrics.

The ramie fabric used in this study is a plain weave type. The ramie woven

fabric was cut into 250 × 190 mm2. Then, some of those cut woven yarn is yanked in the perpendicular

direction to make a unidirectional fabric reinforcement. Since the ramie fiber

has hydrophilic properties and PLA has hydrophobic properties, it is necessary

to apply a surface treatment to the ramie fiber to increase the interfacial

adhesion between both constituents (He et al., 2019). Ramie fiber was soaked in NaOH solution (5% wt) with a ratio of fiber

and solution of 1:10 for 2 hours, then rinsed until the pH reached 7. The fiber

then being dried at room temperature for 12 hours.

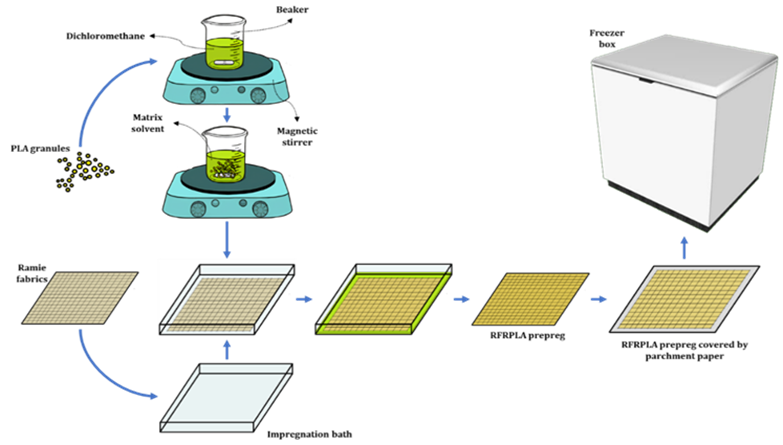

Figure

1 illustrates the flow of the impregnation process. The PLA granules were

dissolved in dichloromethane solvent with a ratio of 1:10 using a magnetic stirrer

for 2 hours at room temperature. The ramie fabric then being manually

impregnated in the PLA/dichloromethane solution. The reinforcement was

impregnated on a glass mold (impregnation bath) of 25.4 × 19.4 cm2

until the matrix was thoroughly pervaded and the excess evaporated. After that,

the resulting prepregs are taken out and covered with parchment paper, as seen

in Figure 2. Then the prepregs were rolled up, and half of the 0/90° one was stored in a

refrigerator freezer at -18°C for a week as a

preserving act.

Figure 1 Impregnation process flow

Figure 2 Prepared

prepregs

2.3. Specimen preparation

Figure

3 shows the flow of RFRPLA prepreg specimen fabrication. Before undergoing a

tensile test, the fabricated prepregs were prepared into a plate specimen

through the hot-press polymerization method. The prepreg sheets made previously

were removed from the parchment paper covering, then stacked in a 25.4 × 19.4

cm2 AA 6061-T6 mold, and then hot pressed at 120°C with 132 bar pressure

for approximately 90 minutes. The composite laminate plate is then cut using

laser cutting according to the geometry of the American Society for Testing and

Materials (ASTM) D3039 standard (ASTM, 2017). Also, some residual-cut specimens will be decomposed as

biodegradability test samples.

Figure 3 Specimen preparation flow

2.4. Characterization

2.4.1. Tensile test

Tensile tests are

carried out according to the ASTM D3039/D3039M standard. The RFRPLA specimens

were tested on the Tinius Olsen universal uniaxial testing machine at the

Metallurgy and Materials Research Center (P2MM) LIPI. The machines were

equipped with a 30 kN load cell with a 2 mm/min displacement rate. The test was

performed on four samples, consisting of a unidirectional (UD) sample, unstored

bidirectional (BD) 0/90° sample, freezer-stored BD 0/90° sample, and BD ±45° sample.

The test was also performed on 6 (six) duplicated specimens of each sample.

2.4.2. Biodegradability

test

The biodegradability test was carried out to see the decomposition process in the RFRPLA composite. This test is carried out by placing a small sample on the soil with actual composting conditions. The sample used was the unused cut of unstored 0/90° RFRPLA prepregs laminate plate. Those samples were used as the control sample depicts any other unstored samples. The test sample consists of two sizes, Sample A (5cm x 5cm) and Sample B (2.5 cm x 5 cm), with four duplications, respectively. The composting condition consisted of cow dung, wood shavings, and animal feed waste placed in a wooden box with a width of 0.5 m, length of 0.6 m, and height of 0.3 m. The decomposition process of the composite was measured by mass change and observed for 120 days to see changes in the shape and color of the sample.

3.1. Prepreg

fabrication

Figure

4

0/90° Prepreg: (a) Unstored; and (b) Freezer-stored

3.2. Tensile properties

A couple of tensile tests

were conducted to determine the mechanical characteristics of the RFRPLA

composite. Table 1 shows the Ultimate Tensile Strength, 0.2% Offset Stress,

Strain, and Young Modulus data from the tested specimens, while Figure 5 shows

the stress-strain trajectory of the tested prepreg laminates.

Table 1 Tensile test results

|

Prepregs condition |

Specimen code |

Ultimate tensile stress |

0.2% offset stress |

Ultimate tensile strain |

Modulus |

|

MPa |

MPa |

GPa | |||

|

Unstored |

UD-A |

53.58 |

27.00 |

3.67% |

1.95 |

|

UD-B |

40.87 |

35.40 |

2.57% |

2.01 | |

|

UD-C |

42.10 |

32.60 |

2.82% |

1.87 | |

|

UD-D |

39.07 |

29.80 |

2.62% |

1.69 | |

|

UD-E |

46.97 |

42.50 |

2.94% |

2.49 | |

|

UD-F |

54.15 |

34.20 |

3.27% |

1.60 | |

|

Average |

46.12 |

33.58 |

2.98% |

1.93 | |

|

St. dev. |

6.55 |

5.33 |

0.42% |

0.31 | |

|

Unstored |

BD090-1-A |

45.87 |

19.00 |

5.37% |

1.77 |

|

BD090-1-B |

42.84 |

18.60 |

5.49% |

2.08 | |

|

BD090-1-C |

47.58 |

20.30 |

5.29% |

0.74 | |

|

BD090-1-D |

47.71 |

19.10 |

5.93% |

0.91 | |

|

BD090-1-E |

45.58 |

18.50 |

5.61% |

0.96 | |

|

BD090-1-F |

49.30 |

26.10 |

5.41% |

1.28 | |

|

Average |

46.48 |

20.27 |

5.52% |

1.29 | |

|

St. dev. |

2.24 |

2.93 |

0.23% |

0.53 | |

|

Freezer-stored |

BD090-2-A |

74.10 |

34.30 |

4.25% |

1.65 |

|

BD090-2-B |

78.12 |

32.10 |

4.44% |

1.83 | |

|

BD090-2-C |

65.43 |

32.10 |

3.32% |

3.44 | |

|

BD090-2-D |

68.36 |

30.50 |

3.95% |

2.56 | |

|

BD090-2-E |

74.10 |

33.30 |

3.83% |

4.52 | |

|

BD090-2-F |

68.55 |

27.40 |

4.13% |

2.18 | |

|

Average |

71.44 |

31.62 |

3.99% |

2.70 | |

|

St. dev. |

4.75 |

2.43 |

0.39% |

1.10 | |

|

Unstored |

BD45-A |

48.42 |

27.80 |

6.28% |

2.82 |

|

BD45-B |

45.44 |

22.60 |

8.17% |

0.62 | |

|

BD45-C |

51.95 |

21.70 |

10.74% |

1.73 | |

|

BD45-D |

38.39 |

24.30 |

5.61% |

1.35 | |

|

BD45-E |

46.42 |

28.70 |

5.85% |

2.22 | |

|

BD45-F |

40.02 |

24.90 |

5.04% |

1.80 | |

|

Average |

45.11 |

25.00 |

6.95% |

1.76 | |

|

St. dev. |

5.11 |

2.78 |

2.14% |

0.75 |

|

Figure

5 Stress-strain

curves of 4 tested samples according to the preparation condition |

The tensile test

results obtained showed various results. It is probably caused by the

manufacturing imperfection, which during the preparation stage, the PLA matrix

solution was not evenly distributed, resulting in the difference in each specimen's

tensile strength. Whereas in unidirectional fiber, there are differences in

fiber density due to misalignment of the fibers, so the ability of the fiber to

accept the load on each specimen is different. The manuality of the process

causes the misalignment in the unidirectional composite laminate, so the fiber

alignment is quite challenging.

Table 1 and Figure 5 shows

that the freezer-stored 0/90° prepregs composite specimen (BD-0/90-2) had the

highest ultimate tensile strength, with an overall average of 71.44 MPa, which

also has the highest average Young's modulus of 2.70 GPa. The unstored 0/90° prepregs

composite specimen has the lowest average Young's modulus of 1.29 GPa, which

can be declared the most elastic composite.

Generally, the yield

point indicates the maximum stress value material can accept before undergoing

plastic deformation. However, there are two failure modes in composites: matrix

and fiber failure modes. Graphically, the yield point cannot be seen clearly on

the composite tensile test result curve. Therefore, 0.2% offset stress was used

to determine the yield strength of the composite.

The matrix density mentioned in section 3.1

also influences the composite laminate's tensile strength, as seen in Table 1. From

Table 1, the freezer-stored prepreg composite has the highest tensile strength.

This phenomenon can be studied further in future research.

Figure

6 Microscopic view of

the damaged specimens: (a) Unidirectional laminates; (b) Unstored 0/90°

laminates; (c) Freezer-stored 0/90° laminates; and (d) ±45° laminates

3.3. Biodegradability

The biodegradability

test samples were observed visually by observing changes in color and shape of

the sample from day 0 to day 120. The biodegradability test sample in this

study did not experience a significant change in shape, but changes in the

color of the sample could be seen. It is caused by water and soil content

absorption into the sample. The absorption of water and soil caused the samples

to undergo weathering, which indicated that the samples from the RFRPLA

composite in this study were biodegradable. Figure 7 shows the final condition

of the decomposition samples, which suffer discoloration and weathering.

Figure 7 Final

(120 days-long) discoloration and weathering of the test samples

Figure 8 shows that the

change in mass that occurs in each sample is not very significant due to the

absorption of water and compost in the test sample, which affects the mass of

the sample. Therefore, the test sample must be dried first and weighed again. Table

2 shows the mass reduction of each test sample before and after the

biodegradability test and drying. The reduction in sample mass (averaging

21.15%) indicates that the test sample has been biodegraded.

Figure

8 Biodegradability test

samples' mass evolution

Table 2 Decomposition mass comparison

of biodegradability test samples after 120 days

|

Specimen

number |

Mass

(g) |

Mass

loss percentage | |

|

Before |

After | ||

|

A1 |

6.1 |

5.8 |

4.92% |

|

A2 |

5.3 |

4.2 |

20.75% |

|

A3 |

6.6 |

6.4 |

3.03% |

|

A4 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

16.67% |

|

B1 |

2.7 |

1.7 |

37.04% |

|

B2 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

34.62% |

|

B3 |

2.7 |

1.7 |

37.04% |

|

B4 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

15.15% |

|

Average |

21.15% | ||

Figure 9a is a

control sample stored for comparison with the biodegradability test sample. A

significant difference between the control and tested samples can be seen. In

Figure 9b, the test sample undergoes biological weathering, which causes the

fiber layer to erode slowly. Meanwhile, Figures 9c and 9d show the presence of

voids between the fibers and the surface of the sample, which is caused by the

decomposition of the PLA matrix.

Figure 9 (a) Control sample; and (b)(c)(d) weathering and decomposition of the test sample

The

fabrication and characterization of pre-impregnated RFRPLA composite were carried

out. Freezer-storing (at a temperature of –18°C) a prepreg apparently can

preserve and increases its mechanical properties. The tensile test found that

the freezer-stored 0/90° prepregs composite had the highest average ultimate

tensile strength of 71.44 MPa and had the lowest elasticity level with an

average Young's modulus of 2.70 GPa. Meanwhile, the unstored 0/90° prepregs composite had the highest level

of elasticity with an average Young's modulus of 1.29 GPa. In the biodegradability

test, the test sample underwent weathering after 120 days, marked by a change

in color and mass in the sample. The microscopic observations on prepregs

showed different structures between the freezer-stored and unstored ones. In

the tensile test specimen, it can be seen that there is good adhesion between

the matrix and the fiber. Microscopic observations on the biodegradability test

samples showed the presence of weathering and decomposition processes.

This

research has been funded under PMDSU (Pendidikan Magister menuju Doktor untuk

Sarjana Unggul) Program by the Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher

Education of Republic Indonesia through NKB-869/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2022 contract

number.

Alsaeed, T., Yousif, B., Ku, H., 2013.

The Potential of Using Date

Palm Fibres

as Reinforcement for Polymeric Composites.

Materials & Design, Volume 43, pp. 177–184

ASTM 2017. ASTM

D3039/D3039M-17. Standard Test Method for

Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. West

Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing and Materials International

Baghaei, B., Skrifvars,

M., 2016. Characterisation of Polylactic Acid

Biocomposites Made

from Prepregs

Composed of Woven Polylactic

Acid/Hemp–lyocell Hybrid

Yarn Fabrics.

Composites Part A: Applied Science and

Manufacturing, Volume 81, pp. 139–144

Baghaei, B., Skrifvars, M., Berglin,

L., 2013. Manufacture and Characterisation of Thermoplastic Composites

Made from PLA/Hemp

Co-wrapped

Hybrid Yarn

Prepregs. Composites

Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, Volume

50, pp. 93–101

Baghaei, B., Skrifvars, M., Berglin,

L., 2015. Characterization of Thermoplastic Natural

Fibre Composites

Made from Woven

Hybrid Yarn

Prepregs with Different

Weave Pattern.

Composites Part A: Applied Science and

Manufacturing, Volume 76, pp. 154–161

Bhardwaj,

R., Mohanty,

A.K., 2007. Advances in the Properties of Polylactides

Based Materials:

A Review. Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy,

Volume 1, pp.

191–209

Bhatnagar, A., Arvidson, B.,

Pataki, W., 2006. Prepreg Ballistic

Composites. Lightweight Ballistic

Composites.

Elsevier, pp. 272–304

Cairns, D., Skramstad,

J., Mandell,

J., 2012. Evaluation of Hand Lay-up

and Resin Transfer Molding

in Composite Wind

Turbine Blade Structures.

In: 20th 2001

ASME Wind Energy Symposium, 2001. Volume 24

Duhovic, M., Bhattacharyya,

D., 2011. 8 - Knitted Fabric Composites.

In: AU, K.F., (ed.) Advances

in Knitting Technology. Woodhead Publishing, pp.

193–212

Faruk, O., Bledzki,

A K., Fink, H-P., Sain,

M., 2012. Biocomposites Reinforced with Natural

Fibers: 2000–2010. Progress in Polymer

Science, Volume 37, pp. 1552–1596

He, H., Tay,

T.E., Wang, Z., Duan, Z.,

2019. The Strengthening of Woven Jute Fiber/Polylactide Biocomposite

without Loss of Ductility Using

Rigid Core–soft

Shell Nanoparticles.

Journal of Materials Science, Volume 54, pp. 4984–4996

Holbery, J., Houston,

D., 2006. Natural-fiber-reinforced Polymer Composites

in Automotive Applications.

Jom, Volume

58, pp. 80–86

John, M.J., Varughese,

K.T., Thomas,

S., 2008. Green Composites

from Natural Fibers and Natural

Rubber: Effect

of Fiber Ratio

on Mechanical and Swelling

Characteristics. Journal of Natural Fibers, Volume 5, pp. 47–60

Lololau, A., Soemardi, T.P., Purnama, H., Polit,

O., 2021. Composite Multiaxial Mechanics:

Laminate Design Optimization of Taper-less

Wind Turbine Blades with Ramie Fiber-Reinforced Polylactic Acid. International Journal of Technology, Volume 12(6), pp. 1273–1287

Lotfi, A., Li,

H., Dao,

D.V., 2019. Machinability Analysis in Drilling

Flax Fiber-reinforced

Polylactic Acid

Bio-composite Laminates.

International

Journal of Materials Metallurgical Engineering, Volume 13, pp. 443–447

McGregor, O.P.L., Duhovic, M., Somashekar, A.A., Bhattacharyya,

D., 2017. Pre-impregnated Natural Fibre-thermoplastic

Composite Tape

Manufacture Using

a Novel Process.

Composites Part A: Applied Science and

Manufacturing, Volume 101, pp. 59–71

Potluri, P., Nawaz, S., 2011. 14 - Developments in Braided Fabrics.

In: Specialist Yarn and Fabric Structures, Gong, R.H., (ed.),

Woodhead Publishing, pp. 333–353

Seferis, J.C., Velisaris, C.N., Drakonakis,

V.M., 2011. Prepreg Manufacturing. Wiley Encyclopedia of Composites, pp. 1–10

Siakeng, R., Jawaid, M., Ariffin,

H., Sapuan, S., Asim, M., Saba, N.,

2019. Natural Fiber Reinforced Polylactic

Acid Composites:

A Review. Polymer

Composites, Volume 40, pp. 446–463

Wang, Y., Chea,

M.K., Belnoue, J.P-H.,

Kratz, J., Ivanov, D.S., Hallett, S.R., 2020. Experimental Characterisation of the in-plane Shear Behaviour

of UD Thermoset Prepregs Under

Processing Conditions.

Composites Part A: Applied Science and

Manufacturing, Volume 133, p. 105865

Wolff-Fabris,

F., Lengsfeld, H., Kramer,

J., 2016. 2 - Prepregs and Their Precursors. In: Composite Technology, Lengsfled,

H., Wolff-Fabris, F., Krämer,

J., Lacalle, J., Altstädt, V., (ed.),

Hanser, pp. 11–25