Intersectionality Lens to Female Elderly's Mobile Usage Experience under COVID-19: An Intimate or Intimidating Relationship?

Corresponding email: 1161100234@student.mmu.edu.my

Published at : 03 Nov 2022

Volume : IJtech

Vol 13, No 6 (2022)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i6.5920

Tan, J.Y., Koo, A.C., Wong, C.Y., Lai, W.T., 2022. Intersectionality Lens to Female Elderly's Mobile Usage Experience under COVID-19: An Intimate or Intimidating Relationship? International Journal of Technology. Volume 13(6), pp. 1282-1297

| Jia Yue Tan | Faculty of Creative Multimedia, Multimedia University, 63100 Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia |

| Ah Choo Koo | Faculty of Creative Multimedia, Multimedia University, 63100 Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia |

| Chui Yin Wong | User and Developer Experience (UXDX), Developer Relations (DevRel), Network and Edge Group (NEX), Intel Corporation, 11900 Malaysia |

| Wan Teng Lai | Corporation, 11900 Malaysia 3Unit for Research on Women and Gender (KANITA), School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 USM, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia |

Due to the

unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic, mobile technologies, services, and Internet

connectivity have become critical among the Malaysian elderly as an alternative

to staying actively and socially connected. However, the elderly find it

difficult to adapt to online technology tools with restricted skills under

technology challenges. Studies related to mobile adoption and usage experiences

among the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic or endemic are not rigorously

conducted by researchers. Little discussion was focused specifically on aging

and gender perspectives, including the importance of an intersectionality lens

in understanding the interconnected factors that influence one's ability to

benefit from technology. To fill in the research gaps, this paper aims to use

an intersectionality lens to identify experiences on how female elderly use

their mobile phones and services, as women are constantly underrepresented in

Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM) studies. The study

employed qualitative case studies method with seven older women in Malaysia, 60

to 77 years old, using multiple data sources through semi-structured

interviews, mobile walkthrough, and diary studies. Data were transcribed and

analyzed by categorizing the key themes digitally using Nvivo. The findings

showed that mobile culture and supportive environment; family roles;

socialization; education and economic backgrounds; digital literacy level;

well-being; and motivation were interconnected, shaping the experiences of the

seven female elderly in accessing, learning, and using their mobile phones.

This study has built an understanding of the intersecting factors that can

contribute to a more inclusive society, especially in promoting the elderly to

embrace mobile technologies in their lives.

COVID-19; Female elderly; Gender; Intersectionality; Mobile phone usage

The impact of the unprecedented COVID-19

pandemic has accelerated the need for digitalization among all walks of life,

including the elderly, as they are one of the most vulnerable groups (Chang et al., 2020). The only alternative to stay

socially connected are through online and digital technologies in this

"new normal" (He et al., 2021),

particularly the most basic communication devices like mobile phones and

services that have become a necessity to all. Previous studies in Malaysia

under the pre-pandemic revealed a mismatch between seniors' requirements and

smartphone application design, with many of them still

In Malaysia, female mobile phone users

were still relatively lower (41.6%) as compared to male users (58.4%) (MCMC, 2019). Based on the World Economic Forum (2021) reported on the global gender gap

(under Malaysia), females had lower percentages in STEM’s (Science, Technology,

Engineering, and Mathematics) (female 26.20% versus (vs) male 57.33%) and ICT’s

(Information and Communication Technologies) (female 6.17% vs male 8.23%)

education and skills attainment (World Economic

Forum, 2021). This reflects that males are still the dominant group in

STEM sectors and technological adoption or development. Generally, the key

barriers for women to own smartphones and access to mobile Internet are

affordability, low literacy and skills, safety and security issues, disapproval

by family, and perceived irrelevance (GSMA, 2020; OECD,

2019). Thus, the focus of the current paper is to study female elderly's

perspectives on using smartphone technologies and to identify issues and

challenges faced by them, in order to create a more digitally inclusive

Malaysia (EPU, 2021b).

Furthermore, this

study takes on a new leap in addressing the importance of gender analysis by

utilizing non-binary perspectives (beyond the biological definitions of male

and female). Its intent is to view gender as a social-cultural process

(European Commission, 2013) that influences how people perform certain roles or

are obliged to certain norms through the usage of technological tools. The

adoption of the intersectionality lens (Columbia

Law School, 2017) is used to provide a broader perspective on how the

experiences of female elderly mobile users can be influenced and shaped by

different overlapping variables, and gender itself as a social factor is

insufficient to address either dominance or subordinate position (Ceia et al., 2021; Rodriguez, 2018).

This paper aims to use an

intersectionality lens to identify experiences of how female elderly use their

mobile phones and services under the COVID-19 norm. Section 2 consists of a

literature review, followed by methodology, data analysis, and results, and

lastly, the discussion and conclusion sections.

Literature Review

2.1. Impact

of COVID-19 on elderly mobile usage patterns

Adapting to mobile technology services

and the Internet has become critical during the lockdown and social distancing

practice. According to the media sources (Chandran,

2021; Noordin, 2020), several elderly

in Malaysia were reported to have learned and picked up new digital

technologies and skills to assist themselves in their everyday routine, for

instance, the adoption of online shopping (i.e. Lazada & Shopee) in order

for them to buy their household items, clothes or toiletries while staying

indoors. Some had learned to use a laptop or tablet for video-conferencing

platforms, such as Google Meet or Zoom, to join online activities, exercises,

and also communicate with family and friends (Chandran,

2021). One male elderly revealed navigating social media and e-commerce

platforms with the support of his two daughters (Chandran,

2021). Besides, Malaysia's contact tracing app (MySejahtera), e-wallet,

mobile banking, online food delivery, and other services have also been found

to play a key role in assisting the elderly in living through the pandemic (Noordin, 2020; Tandapany, 2020). A recent study

conducted by Ibrahim et al. (2021) during

the pandemic observed that older participants could even operate their mobile

devices and Google Meet platform independently after the training provided by

the researchers. Unfortunately, those elderly who were digitally illiterate or

lack of access to Internet connectivity had left many of them in the lurch (Anand, 2021; Seifert et al., 2021).

2.2. Construction

of gender

Gender appears naturally and deeply

embedded in our social practice; in fact, we are uncertain about how to

interact with or judge people without the attribution of gender to them (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2013). Our society

mainly operates in a binary system (view gender as only two options or

biological definitions of male and female). Therefore, the ways of behaving,

roles, and activities are expected to match the biological sex assigned to a

person, which shapes what is appropriate for being "male" or "female's"

role (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2013).

Gender from a non-binary perspective, is defined as "socially and

culturally constructed" where people learn behaviors, roles, and norms

within the social structures and cultural contexts they live in (Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 2013; European Commission,

2013; Ton, 2018; WHO, n.d.). According to Judith Butler's notion of

"gender is performative", gender is viewed in less normative way,

which implies gender identity is formed through the repetitiveness of acts (Ton, 2018). When certain acts are repeatedly

performed by one of the genders, it becomes a cultural norm representing

gender, and therefore, stereotypes can also be formed. West and Zimmerman's

concept of "doing gender" noted that gender is performed or formed

through everyday interactions, and behaviors are evaluated based on the

societal expectations of gender conceptions (Eckert

& McConnell-Ginet, 2013). The construction of gender (Ton, 2018) influences how people perform those

roles, as well as socially and culturally, how women are expected to be,

obligated to play certain roles within families, such as care, connectivity,

communication, or even among communities. Gender represents not only relations

and identities but also influences the development and design of technologies

or systems, which may enable or inhibit women's participation (Aaltojärvi, 2009).

2.3. Mobile

phone is a place for gender performance

Ganito (2010) mentioned that "a

mobile phone is a place of gender performance, either to reinforce traditional

roles, or to transform gender, constructing new meanings." Mobile phone

blur the boundaries across multiple practices (work, professionals, private,

leisure) when it is embedded in everyday life (Ganito,

2010), it can be a medium where people carry out their traditional

gendered identities, such as activities regarded as appropriate for men

(practical work and enhancing digital skills) and women (domesticity and

communication) (Lemish & Cohen, 2005).

It can also be a medium that enables changes (beyond the traditional

practices), for instance, women have increasingly become the power users of

technology, with a growing interest in technological devices; they tend to

purchase gadgets, learn new digital skills and become producers. This reflects

that women are able to perform new cultural meanings through the adoption of

mobile phones (Ganito, 2010; Skog, 2002).

Thus, mobile phones can empower women to challenge the socially expected

gendered behaviors and reduce unequal gender power relationships, particularly

to assist the socially marginalized women in attaining socio-economic status (Pei & Chib, 2020). However, it is arguable

that mobile phones can also disempower women if they are still bound to the

patriarchal oppression in domesticity and society. For instance, women lack

decision-making power in their patriarchal households despite their economic

empowerment through the adoption of mobile phones (Pei

& Chib, 2020). In the social-psychological perspectives, the

masculine assumption collectively shaped the negative stereotype that women

were "chatterboxes", "less tech-savvy users," and

"less interested in ICT", whereas men were perceived positively as

"tech-savvy" and "have higher competence" when it comes to

technology adoption and usage performance (Comunello

et al., 2016; Gales & Hubner, 2020). Additionally, the biased

perception that older individuals were less competent than younger ones in

technology usage added more negative stereotypes for female elderly users (Comunello et al., 2016).

2.4. Intersectionality

lens for explaining relationships

Intersectionality, introduced by legal scholar

Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) is a theory that originally highlights how

marginalized social groups exist on the periphery of society, with unequal

access to resources and opportunities (Fehrenbacher

& Patel, 2020). The purpose of intersectionality is to illustrate

the interconnected nature of more than one aspect rather than independently

that influences individuals’ or groups' identities and experiences of

privileges or oppressions (Rogers et al., 2020).

Gender is only one of the social factors people face in every part of the

world. It is still insufficient to address either a dominant or subordinate

position (Ceia et al., 2021; Rodriguez, 2018).

Thus, intersectionality helps to address the other factors expanding to the

influence of, for instance, the ethnic groups of Malay, Chinese, and Indian in

Malaysia, age, education level, economic status, ability, and religious or

cultural practices (Ceia et al., 2021).

Based on the theory of intersectionality, all these identities and categories

are interlocked, resulting in various experiences and characteristics,

including the formation of stereotypes and inequalities among the local female

elderly mobile user group.

2.5. Online

research set-up and conducts

During the COVID-19 pandemic, conducting

qualitative research through online interviews or group interviews has become

the last resort due to restricted movement. Researchers have to rely on

technologies, particularly video conferencing software, multimedia computer,

and connectivity, to enable the setting of interview sessions. Dodds & Hess (2020) identified the advantages

of using online group interviews for qualitative research. Their findings

showed the benefits of online media when conducting research. The benefits of

online interviews enable both researchers and participants to feel comfortable,

non-intrusive, and safe; engaging and convenient; direct communication; and

easy set-up. However, one key aspect of the limitations is the lack of non-verbal

communication. Other issues are poor device set-up and privacy intrusion and

access issues.

In sum, the adoption of mobile phones

and participation in the digital world not only improves the lives of older

populations but also empower elderly females, their families, and communities

in helping to reduce gender inequalities. In Malaysia, several gender studies

have been found to investigate mainly the interests of students and adolescents

in relation to their usage and adoption of digital technologies (Ahmad et al., 2019; Aziz & Aziz, 2020; Maon et al.,

2021). However, there is a lack of research and discussion focused

specifically on aging and gender perspectives, including the insignificant use

of intersectionality as an important lens to understand the formation of power,

privileges, and gender inequalities. Therefore, the intersectionality lens is

used in this study to better understand the relationships between age, gender,

and individuals' unique interaction with mobile phones and services.

This research employed qualitative case

studies as an empirical method in enabling researchers to gain in-depth insight

into how female elderly (as individuals) interact and experience their mobile

phones within the real-life context (Yin, 2018).

As the focus of this study is on the female elderly, thus, the criteria for

selecting the participants were female who 1) aged 60 years old and above, 2)

lives in Klang Valley (center of the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia), 3)

have at least three months of smartphone usage experience, and 4) stay with at

least one of the family members. Participants were recruited either from a

senior learning community or by snowballing method (introduced by

participants).

The study utilized an online medium for conducting

an in-depth study of seven cases of elderly women. There are three main

activities during the study, which are 1) in-depth interview, 2) mobile

walkthrough, and 3) diary writing, followed by a diary explanation designed by

the research team, hosted, and led by the first author. Prior to conducting the

study, an introductory session was conducted with each participant. They were

briefed about the three activities of the study. Their consent to participate

in the study was sought by signing the informed consent form. At the end of the

study, all participants were given a token to thank them for their efforts and

time commitments.

All of the above meeting sessions were

conducted via Zoom video meetings and supported by communication tools, i.e.,

computer, WhatsApp, Adobe Fill and Sign, and Zoom screen sharing feature.

Despite the drawback of not being able to meet the participants in person with

insufficient non-verbal communication clues on the bodily reaction, the rest of

the non-verbal communication, such as facial expressions, could be clearly seen

via the video. The other features and support tools or virtual space provided

by Zoom were supportive towards research set-up, such as recording of the

sessions, making online interaction with research participants at ease and

convenient, non-intrusive, and safe.

The data was collected until it met a

saturation point where no new or refreshed data was found (Saunders et al., 2018). After the data collection

ended, recorded videos were transcribed into text-based data for data analysis.

All the primary data were coded, categorized, and analyzed using NVivo 12

software to identify key patterns (themes) of meanings (Braun

& Clarke, 2006).

This section presents the results from the case studies on female

elderly's mobile phones and services usage experience in daily lives and their

perceptions. The findings were grouped into the following themes and discussed

accordingly.

4.1.

Participants' Demographic and Mobile Status

A total of seven

participants (see Table 1) aged between

60-77 years old were recruited for the study. Since Malaysia is a multi-racial

and cultural country, the participants comprised of three main ethnic groups - Malay, Chinese and Indian - to study the diverse

mobile culture. All of them are married except P2 is single, and P6 is a widow.

There is also no surprise that three of the participants were involved in

interracial marriages (P1 with Malay, P3 with Indian, and P5 with Chinese) in

Malaysian society. Regarding their employment status, five participants are

retirees and three female elderly are housewives. Participants who

worked before are supported by their retirement savings or monthly pensions for

their living. Two participants work as part-timers or engage in investment

activities to earn their passive income. In contrast, participants who are

housewives receive income support or pocket money from their spouses or

children.

Table 1 Participants' demographics and mobile status

|

Participants |

Age |

Race/ Ethnicity |

Employment Status |

Education Level |

Marital Status |

Financial Status |

Mobile Phone Background |

|

P1 |

60 |

Chinese |

Housewife |

Tertiary |

Married (Interracial marriage) |

Supported by spouse and children |

Huawei smartphone. Had 9 years of

smartphone usage experience. |

|

P2 |

64 |

Chinese |

Retiree |

Secondary |

Single (All-time) |

Retirement fund, investment as passive income |

Huawei smartphone. Had 9 years of

smartphone usage experience. |

|

P3 |

63 |

Chinese |

Housewife |

Secondary |

Married (Interracial marriage) |

Supported by spouse and children |

Oppo smartphone. Had 4 years of

smartphone usage experience. |

|

P4 |

61 |

Malay |

Retiree |

Tertiary |

Married |

Working savings, passive income |

Samsung smartphone. Had

5 years of smartphone usage experience. |

|

P5 |

62 |

Malay |

Retiree |

Tertiary |

Married (Interracial marriage) |

Monthly pension, supported by children |

Samsung smartphone. Had

5 years of smartphone usage experience. |

|

P6 |

72 |

Indian |

Retiree |

Tertiary |

Widow |

Monthly pension, part-time income,

supported by children. |

Oppo smartphone. Had 6 years of

smartphone usage experience. |

|

P7 |

77 |

Indian |

Housewife |

Secondary |

Married |

Supported by spouse and children |

Samsung smartphone. Had

3 years of smartphone usage experience. |

Nevertheless, expenditure for their

mobile phone and infrastructure is not much an issue among the participants as

their retirement scheme or family members financially support them. Due to its location at Klang Valley, Selangor

(the most developed state in Malaysia), most had received tertiaryeducation

(i.e., college, polytechnic, university), followed by upper secondary

education. Overall, all seven participants owned a smartphone. Before, they had around 3 - 9 years of experience in

using smartphones, indicating that they are not new smartphone adopters. Table 1 provides an overview of the

demographics and mobile status of the participants.

4.2. Female

elderly mobile usage experiences

Participants

described their general experiences and relationships regarding their

smartphone and mobile services usage. Five sub-themes emerged under this theme:

4.2.1. Connectivity and

Accessibility

Connectedness and

accessible are the

main aspects for the female elderly to develop intimacy with their mobile

phones, whether in their everyday lives or during the lockdown imposed.

Participants were still able to foster close connections with their family

members, friends, and acquaintances mainly via the usage of WhatsApp (a popular

communication app in Malaysia) video calls, voice, or text messaging. Besides,

the participants experienced

accessibility because it is convenient for them to reach a particular person, sources of information, and

services anytime or anywhere. Mobile phones could be identified as a "time-saving" tool that allows

the participants to keep

themselves updated, make purchases, join online activities, and schedule

appointments without much effort.

"Usually, [when using] smartphone, we are very happy

with WhatsApp because near and far you can just connect within seconds, you

know." (P3)

It

is also interesting to learn about Malaysia's unique mobile culture and how

participants of various ethnic backgrounds use their phones to stay connected

with their families and social networks daily. The findings reported a similar

pattern among the Malay, Chinese and Indian participants, where they tend to

send greetings and wishes (in an e-card format of their own language; see Figure 1) as part of every morning routine or

during any celebrations in their social groups. P5, who is engaged

in an interracial marriage, is an open-minded woman who always takes the

initiative to design e-cards associated with different languages and send them

to her family groups to maintain close and harmonious relationships:

"Yes, like I will put up our family photos [refers to editing] you know, when Hari Raya, Chinese New Year in our family photos to be the wishes, then we can post it. We did it a lot here because my family has Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims."

Figure 1 E-card greetings sent by

participants with different ethnicity

Nevertheless,

connectedness is associated not only with kinships and friendships but also

with the extent of social connectedness to any happenings occurring nationally

and internationally. Reading news

(i.e., politics, social affairs, COVID-19 updates) is quite a common activity

for all the participants to keep themselves updated and connected with the

outside world while being retired or at home, as P7 expressed her sentimental feelings after reading online news of

an Indian young man:

"Then while browsing through the Google, [I] came across the

hanging of NaD [Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, a Malaysian due to his injustice

execution case], felt very sad." (P7's diary)

4.2.2. Essentiality and Dependency: An "intimate" Relationship for

Fulfilling Basic Needs

Smartphone has become an intimate

tool to all the participants in the sense that they felt insecure, desperate or

even "despair" without it, as

they conveyed:

"Without a phone, we're desperate." (P6)

"Very important, this phone, it's like our

second IC [Identity Card]

already. [If I] don't have a phone, I can't survive." (P2)

Since

the implementation of the lockdown, the participants have developed a stronger

bond with their smartphones. The

participants were increasingly becoming

dependent on their phone as it was essential and helpful in many ways to serve their daily routines and needs. Their mobile phone assisted them in coping with the feeling of isolation and anxiety while staying at

home or indoors for a long period during movement control orders (MCO) imposed

by the Malaysian government. When asked

how they felt about their relations with smartphones, one of them stated:

"Of course, we spend more time with handphone

than anything else… I mean, we [used to] travel, we go out, we don't spend so much time on the

phone, you see, now [during the lockdown] you got nothing else but the

phone." (P1)

Apart from communication,

several participants revealed that they spent more time accessing

information (i.e., news, updates, live videos) through mobile web browsers, applications

(such as Google and YouTube), or social media platforms. Other mobile services, such

as location-based apps, tend to ease

traveling and provide location guides, online shopping, food

delivery, e-banking, and e-wallet, which were essential apps for

household convenience with minimal traveling. In terms of safety, Malaysia's contact tracing app (i.e.,

MySejahtera) was created to facilitate contact tracing efforts which were

compulsory for all Malaysians, including the elderly, during the COVID-19

outbreaks.

Due to the MCO, all

female elderly utilized their phone to aid them in maintaining good health and

well-being (in the aspects of physical, emotional, and mental health).

For instance, the participants recognized the importance of

playing brain teaser games to stimulate their brains and prevent old-age

diseases such as dementia.

Some of them engaged in virtual

exercises, leisure, or spiritual activities to continue to stay fit and active.

One of the participants (P2) reflected in her diary and wrote:

"Singing exercises your heart and lung, and

releases endorphins, making you feel good."

4.2.3. Discovery and Exploration of the "wonder" of application

features

Positive

affection (relates to moods, feelings, and attitudes) can be one of the key

motivators for participants to continue learning or using mobile apps and

services. As such, participants

expressed their new discovery and pleasure of using various mobile apps.

These discovering experiences resulted from a mixture of affection and

discovery feelings (such as enjoyment, excitement, fun, etc.) and learning

experiences:

"Love this wonderful social website where we

can collect and share, imagine of anything you find interesting." (P2's

diary)

"The [crossword puzzle] game was quite the brain

teaser and I enjoyed myself." (P3's diary)

The

findings also revealed that smartphone benefits most participants due to the

existence of free app or web-based services, unlimited cloud storage and

membership privileges, particularly free communication services, which could

assist female elderly in establishing family and social ties (locally and

globally) without worrying about the cost. In this regard, the

participants expressed their sense of

enjoyment and satisfaction of these services:

"It's great that we can talk free of charge on

WhatsApp!! How awesome (P6's diary)

"Shopee [e-shopping app] you will have free

delivery, or you have coins [rebate voucher], you can collect coins...

benefit for Shopee user." (P1)

Besides,

few participants expressed their gratitude not only to the invention of mobile

phones but also to the "pandemic", because both had afforded them more opportunities to empower or enrich

themselves intellectually and digitally.

4.2.4. Concerns about online fraud and security issues

Despite the advantages and affection (intimacy) feeling towards their

mobile phones, one of the biggest worries by all participants are issues on

cybersecurity (hackers) and frauds (scams and fake news). Many of the female

elderly (4 out of 7 participants) had experienced receiving scams or unknown

calls and messages (6 out of 7 participants) received fake news before, which

made them anxious and cautious. Therefore, they were very mindful in handling

any calls and took every protection measure they could to prevent online scams

and frauds. They took the initiative to download security apps (TrueCaller ID),

read or share news to increase fraud awareness with friends and family, filter

fake information, and check for reliable sources.

"I stopped forwarding or you know, when I

received something, I'm very cautious about what I forward to, and I always

say, 'please check if it's genuine.'” (P4)

“You have to be really aware of the danger of your

accounts, scams, and all those; that is the most difficult part.” (P5)

Moreover,

security and trust issues have posed a challenge among female elderly

participants, particularly those who were less tech-savvy in the penetration of

mobile banking, e-transaction, and payment services in the current society. Two

participants revealed they preferred not to adopt it or use it with the guidance of family members:

“Very worry about scams. That’s why I dare not do

anything online, but even going banking online, I resisted a lot.” (P3)

“So basically, I still pay cash at the counter or I

go to the Petronas [petrol station] and pay that kind of thing. I haven't really used

the online payment just yet.” (P4)

4.2.5. Challenges faced by aged users

Other potential barriers reported by the participants were old-age

barriers, lack of motivation, and circle of support. As they age, it is common

for the elderly to experience a deterioration in visual and cognitive abilities.

Five participants commented the phone screen size is still restricted for them

to view a bigger picture whenever they want to read information or participate

in online activities. Therefore, they use it interchangeably with their

computers. Log-in to an app with a password is a challenge for the female

elderly as they tend to forget their password easily.

“I forgot my password. Maybe people like us, we are

very careless about the password, you know, not like you young people…” (P3)

Besides, few factors caused motivational issues.

For example, the participants discontinued the use of some mobile applications

or features that were inconvenient or complicated to use; three participants

were quite conservative about advancing themselves in using their mobile phones

due to some self-perceived reasons, such as retiring from work, low level of

digital literacy, or security knowledge. Four out of seven participants

reported that they lacked immediate or empathetic support from their family

members and were forced to self-learn and seek external help.

Furthermore, P3 and P7 participants

reflected that smartphones could negatively affect their well-being. For

example, they were aware that they spent too much time on their phones due to

addiction, and it caused them eye-strain issues and nuisance (bombarded with

excessive information). Hence, the awareness to control and the determination

to refrain from spending long hours on their phones should be a solution to

curb the challenges.

4.3. Perceptions of their male counterparts of

using mobile phones and services

Although the male respondents were not

involved in this research, their female counterparts had provided perceptions

of their male counterparts. A mixed

perception occurs that their spouse generally has some differences from them.

Relatively, the participants perceived that their spouse had more interest in

their “male-oriented” topics of interest (i.e., technical, engineering, and adventurous

topics) or as aligning to the gender norms that their spouse were less

socialized by using the phone and had more authority in the financial decision;

whereas topics related to gossip, household purchase matter, entertainment, and

exploration of apps features are more dominance among the females. Indeed,

there is an obvious difference between the gendered use of the mobile phones

and apps of choice:

“I personally think no differences between the gender

on the [digital]

knowledge, it is more of… interests rather than the gender-based.” (P1)

“[…] he [husband] is not the customer, so usually

purchased, I will be the one who purchased.” (P1)

“He [husband] is more into YouTube and looking at what people send

messages and all that [read info and text-messaging]; he doesn't play

games at all.” (P7)

“[…] my husband will download all the [apps]... he's into

cars and engineering and things like that. So, he always looks at all that

kinds of stuff.” (P4)

On

the contrary, there are also participants who observed that their spouse is

less tech-savvy and a conservative user (use only the basic or necessary

functions) compared to themselves. P1 and P5 had mentioned that their spouse

tends to seek technical assistance from them.

“He’s also like me, not so much of smartphone…” (P3)

“He's not IT savvy. Sometimes he sorts of jealous,

you know, envy [laugh], because we are more advanced than him.” (P5)

Discussion

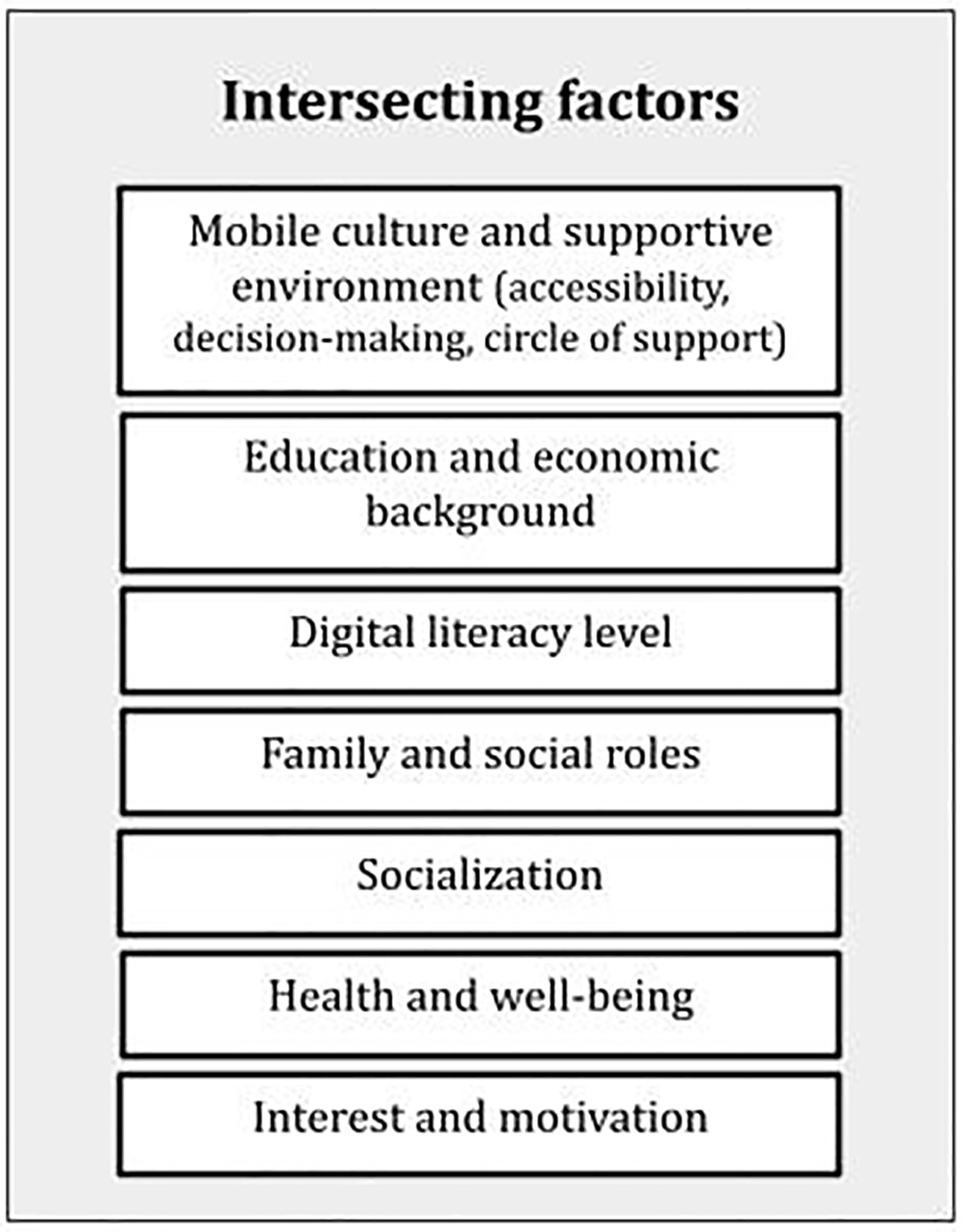

The intersectionality lens in this section

explains the key interconnected factors that shaped the female elderly’s mobile

usage experiences (Figure 2). The findings showed several contributing

factors that influenced the relationship between female elderly and their

mobile phone intimacy as follows:

Figure 2 Key factors identified that shaped female elderly’s mobile usage

experiences

5.1. Female elderly and their access

to mobile infrastructure and apps

Firstly,

the participants could access mobile infrastructure and mobile apps (i.e.,

devices, mobile broadband, and telecommunication services) without many

hindrances. This indicates that the supportive family and mobile culture

environment are essential for their daily phone usage, such as monthly bill

payments, seeking information, e-purchasing, etc., especially since they are

living in an urban context that is undergoing rapid development to Industrial

Revolution 4.0 and digital society (EPU, 2021a).

The factors that influence the female elderly to learn digital skills are

education background, digital literacy level and prior computing experience

acquired through their previous working experience. These intersecting

backgrounds determine their confidence level and learning attitude when

adapting to new technological devices. Besides, it is imperative to have a

higher level of mobile literacy to educate and protect themselves from online

scams and frauds which are very rampant in this digital era.

5.2. Motivating factors leading to

women’s mobile adoption and advancement in new skills

Secondly,

the findings revealed that mobile phones enable female elderly to perform

family and social roles conveniently as well as have the autonomy or

flexibility to organize their everyday lives and personal interests. It is

found that women are still bound to their traditional gender roles as family

caretakers. Mobile apps and online services offer many conveniences to female

elderly for their weekly and monthly purchasing or executing their household

responsibility without much depending on their family members, as indicated by Sitorus et al. (2019) in the mobile banking

context that the intention to continue adopting banking services were strongly

impacted by satisfaction, compatibility, ease of use and usefulness.

Connectedness and accessibility are the main reasons for female

elderly to own mobile phones. According to Ndukwe (2020), “mobile phones afford women the opportunity to build and maintain

multiple relationships,” from family and social ties to casual acquaintances

for shared interests and needs, as well as it could be a “melting pot” of

culture and language for individuals with a different ethnicity to embrace

diverse culture in the Malaysian context. The mobility of a phone allows female elderly to

freely access resources (without time and geographical barriers) to constantly

keep themselves updated and enhanced with knowledge, skills, and general

information, which is why they build a close relationship with their phones.

Mobile phone has also played

a role in increasing female elderly's resilience and adaptability in responding

to many challenges (Berawi, 2020; Sofyan et al.,

2021), including health challenges faced in a pandemic and endemic

situation, while still being able to keep active and productive in an

optimistic way. Commonly, the elderly face health challenges for depression,

anxiety, old-age diseases, and declination of physical ability (World Health

Organisation (WHO), 2021). The present study has discovered that mobile phone is useful and

beneficial for female elderly in self-care, supporting their overall health and

well-being, and developing a culture for them to practice a healthier

lifestyle. The independency gained by mobile phones enables them to spend time

healthily, cope with loneliness, and enrich their lives meaningfully.

Hence,

the prevalent use of mobile phones and services has positively triggered their

intimacy and engagement with their phones. This has resulted in their high

motivation to self-learn and acquire new digital skills.

5.3 Demotivating factors to women’s

mobile phone adoption and skills advancement

On the other hand, the overlapping factors that

cause intimidating experiences to the female elderly are aging barriers, lack

of digital literacy and supportive environment, security concerns, and negative

well-being in using mobile phones and services. Even though they received

technical support (from family or externally), generation gaps existed. Some

participants have perceived difficulties in getting guidance and support from

their children (young people) on mobile technical know-how. In fact, they

mentioned their children are still willing to help or support them, but as they

were committed to their work, they couldn’t spend much time in providing

supportive guidance. Hence, it causes some misperceptions between the female

elderly and the younger ones, where the younger ones are sometimes perceived to

be impatient. However, this may not always be the case. Some misconceptions

maybe happen between the generations.

5.4. Empowerment and gender

transformation

Lastly,

this research also re-examined the stereotypes and power relations associated

with gender and technology. The lens of female elderly on their male

counterparts revealed the gender differences primarily on usage purposes,

interests, and division of roles, implying they encountered less constraints

from their family, religious and social-structural contexts in terms of

technology access and usage, but the reinforcing of traditional gendered roles

still perpetuates. The intersecting background (i.e., urban or sub-urban

location, highly educated, economic empowerment, etc.) has placed this group of

female elderly users in a more privileged and empowering position which

constitutes to more equal gendered power relations between them and their

family members (Pei & Chib, 2020). They not only have the authority in

decision-making from household to personal matters or in helping their spouse

with online tasks and purchasing a phone, but they also value every opportunity

to learn technologies more than men. As a result, as female elderly are

becoming the power users of the smartphone, their experiences and interests

have progressed, which enabled them to keep abreast or even compete with the

male users. Ganito (2010) and Haraway (1991) highlighted that “technology can

empower women or at least allow for gender transformation,” males in this case,

are not necessarily portrayed as advanced mobile phone users or have a strong

interest in learning digital skills as compared to their female counterparts.

Overall, the pandemic has enriched the lives of the

female elderly’s mobile usage experiences and built strong and intimate

relationships with their devices compared to the intimidating experiences.

Mobile phones have promoted connectivity, reachability, intellectuality, and

well-being, especially during the lockdown when mobile services are becoming

essential. The themes or factors identified are the general trends of findings

based on this group of participants only. The intersections of gender grouping

or variables (male and female) have shown the differences in mobile usage and

experiences. The intergeneration group (elder and young people) has shown

differences in perception toward each other’s free time and ability to help

troubleshoot on mobile phone. The culture or ethnicity attribute did not show

much difference in general, but the socio-economic (i.e., mobile expenditure,

self-investment in digital skill class), educational background, and supportive

environment did possess significant impacts on mobile phone usage and

experiences.

Limitations and Future Works

This study's sample sizes were limited;

therefore, it might be argued that the participants were not representative of

the aging population at large of the Malaysian aging population. The main principle

of qualitative research is for researchers to gain in-depth and rich insight of

certain social phenomena, behaviors, or lived experiences of an individual or

focused group. The study did not aim to generalize the findings, so it could be

concluded that the researchers had investigated the “advanced” senior

smartphone users’ group in-depth. Additionally, the researchers are aware of

the biases imposed in this study as it focuses on female elderly residing in

the urban and suburban areas where they experienced more technical advantages

in terms of accessibility and mobile usage capability. The future study plans

to investigate the older-aged group elderly (70-80 years old) in Malaysia

living in semi-urban, lower-income

groups of, their experiences and behavioral patterns in mobile phone usage,

incorporating gender and intergeneration perspectives.

Acknowledgment to the

International Development Research Centre Grant (IDRC, Canada) and Carleton

University through a grant entitled “Designing Mobile Service Design for Ageing

Women in Malaysia”. This is one of the projects, namely Project ID 50, under

Gendered Design for STEAM in LMICs. Grant ID is MMUE 190212/ ID 50, 2020-2022.

Special thanks to the research participants for their willingness in this

study.

Aaltojärvi, I., 2009. Ascribing Gender from Domestic Technologies. In: Proceedings of the 5th

European Symposium on Gender & ICT, pp. 1–7

Ahmad, N.A., Ayub, A.F.M., Khambari, M.N., 2019. Gender Digital

Divide: Digital Skills among Malaysian Secondary School. International

Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development,

Volume 8(4), pp. 668–687

Anand, R., 2021. Current Theme: Malaysia’s Seniors Slow in

Registering for Vaccination. The Straits Times. Available online at https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysias-seniors-slow-in-registering-for-vaccination,

Accessed on March 27, 2021

Aziz, A.A., Aziz, A.A., 2020. The Influence of Gender Differences

on Instagram Usage among Higher Institution Students. International Journal

of Modern Trends in Social Sciences, Volume 3(14), pp. 78–83

Berawi, M.A., 2020. Empowering Healthcare,

Economic, and Social Resilience during Global Pandemic Covid-19. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 11(3), pp. 436–439

Ceia, V., Nothwehr, B., Wagner, L., 2021. Gender and Technology:

A Rights-Based and Intersectional Analysis of Key Trends. Report Oxfam

America

Chandran, S., 2021. Current Theme: Malaysian Senior Citizens More

Adept at Using Technology Thanks to The Pandemic. The Star. Available

online at

https://www.thestar.com.my/lifestyle/living/2021/03/24/how-the-pandemic-has-encouraged-malaysian-senior-citizens-to-become-adept-at-using-technology,

Accessed on March 24, 2021

Chang, F.C., Tan, S., Singau, J.B., Pazim, K.H., Mansur, K., 2020.

The Repercussions of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Well-Being of Older People in

Malaysia: A Literature Review. International Journal for Studies on

Children, Women, Elderly and Disabled, Volume 11, pp. 17–23

Columbia Law School., 2017. Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality,

More than Two Decades Later. Available online at

https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later,

Accessed on September 13, 2021

Comunello, F., Ardèvol, M.F., Mulargia, S., Belotti, F., 2016.

Women, Youth and Everything Else: Age-Based and Gendered Stereotypes in

relation to Digital Technology among Elderly Italian Mobile Phone Users. Media,

Culture & Society, Volume 39(6), pp. 798–815

Dodds, S., Hess, A.C., 2020. Adapting Research Methodology during

COVID-19: Lessons for Transformative Service Research. Journal of Service

Management, Volume 32(2), pp. 203–217

Eckert, P., McConnell-Ginet, S., 2013. An Introduction to Gender:.

In Language and Gender. , (2nd Edition.ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–36

EPU (Economic Planning Unit), 2021a. Malaysia Digital Economy

Blueprint. Report Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department,

Putrajaya, Malaysia

EPU (Economic Planning Unit), 2021b. Twelfth Malaysia Plan,

2021-2025. A Prosperous, Inclusive, Sustainable Malaysia. Report Economic

Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, Putrajaya, Malaysia

European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and

Innovation, 2013. Gendered Innovations: How Gender Analysis Contributes to

Research. Report of The Expert Group 'Innovation Through Gender', Publications

Office

Fehrenbacher, A.E., Patel, D., 2020. Translating the Theory of

Intersectionality into Quantitative and Mixed Methods for Empirical Gender

Transformative Research on Health. Culture, Health & Sexuality,

Volume 22(sup1), pp. 145–160

Gales, A., Hubner, S.V., 2020. Perceptions of the Self Versus One’s

Own Social Group: (Mis)conceptions of Older Women’s Interest in and Competence

with Technology. Frontiers in Psychology, Volume 11, p. 848

Ganito, C., 2010. Women on the Move: The Mobile Phone as a Gender

Technology. Comunicação & Cultura, Volume 9, pp. 77–88

GSMA (Global System for Mobile Communications), 2020. Connected MomenWomen:

The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2020. Report GSM Association

Haraway, D., 1991. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and

Socialist-Feminism in The Late Twentieth Century. In Simians, Cyborgs and

Women: The Reinvention of Nature, New York: Routledge, pp. 149–181

He, W., Zhang, Z.J., Li, W., 2021. Information Technology

Solutions, Challenges, and Suggestions for Tackling the COVID-19 Pandemic. International

Journal of Information Management, Volume 57, p. 102287

Ibrahim, A., Chong, M.C., Khoo, S., Wong, L.P., Chung, I., Tan,

M.P., 2021. Virtual Group Exercises and Psychological Status among

Community-Dwelling Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Feasibility

Study. Geriatrics, Volume 6(1), pp. 1–12

Lemish, D., Cohen, A.A., 2005. On the Gendered Nature of Mobile

Phone Culture in Israel. Sex Roles, Volume 52(7–8), pp. 511–521

Maon, S.N., Hassan, N.M., Jailani, S.F.A.K., Kassim, E.S., 2021.

Gender Differences in Digital Competence among Secondary School Students. International

Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, Volume 15(4), 73–84

MCMC (Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission), 2019.

Handphone User Survey Malaysian 2018. Report Malaysian Communications and

Multimedia Commission, Cyberjaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Ndukwe, C.U., 2020. A Feminist Study of Women Using Mobile

Phones for Empowerment and Social Capital in Kaduna, Nigeria. Doctor's

Dissertation, Graduate Program, University of Salford, Manchester, UK

Noordin, K.A., 2020. Seniors Becoming Digitally Savvy during

Pandemic. The Edge Markets. Available online at https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/seniors-becoming-digitally-savvy-during-pandemic,

Accessed on April 20, 2021

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development),

2019. The Role of Education and Skills in Bridging the Digital Gender Divide.

Report Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation (APEC) Chile’s 2019 Women, SMEs and Inclusive Growth

Priority

Pei, X., Chib, A., 2020. Defining mGender: The Role of Mobile Phone

Use in Gender Construction Processes. In: The Oxford Handbook of Mobile

Communication and Society. Oxford University Press, pp. 517–528

Rodriguez, J.K., 2018. Intersectionality and Qualitative Research.

In: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research

Methods: History and Traditions, SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 429–461

Rogers, W.A., Ramadhani, W.A., Harris, M.T., 2020. Defining Aging

in Place: The Intersectionality of Space, Person, and Time. Innovation in

Aging, Volume 4(4), p. 11

Sani, Z.H.A., Nizam, D.N.M., Baharum, A., Tanalol, S.H., 2020.

Older Adults’ Needs and Worries about Healthy Living and Mobile Technology: A

Focus Group Study. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology,

Volume 29(9), pp. 1127–1136

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker,

S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., Jinks, C., 2018. Saturation in

Qualitative Research: Exploring its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Quality

& Quantity, Volume 52(4), pp. 1893–1907

Seifert, A., Cotten, S. R., Xie, B., 2021. A Double Burden of

Exclusion? Digital and Social Exclusion of Older Adults in times of COVID-19. Journals of Gerontology: Social

Sciences, Volume

76(3), pp. e99–e103

Sitorus, H.M., Govindaraju, R., Wiratmadja,

D.I.I.I., Sudirman, I., 2019. Examining the Role of Usability, Compatibility

and Social Influence in Mobile Banking Adoption in Indonesia. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 10(2), pp. 351–362

Skog, B., 2002. Mobiles and the Norwegian Teen: Identity, Gender

and Class. In: Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk,

Public Performance, Cambridge University Press, pp. 255–273

Sofyan, N., Yuwono, A.H., Harjanto, S.,

Budiyanto, M.A., Wulanza, Y., Putra, N., Kartohardjono, S., Kusrini, E.,

Berawi, M.A., Suwartha, N., Maknun, I.J., Yatmo, Y.A., Atmodiwirjo, P., Asvial,

M., Harwahyu, R., Suryanegara, M., Setiawan, E.A., Zagloel, T.Y.M., Surjandari,

I., 2021. Resilience and Adaptability for a Post-Pandemic World: Exploring

Technology to Enhance Environmental Sustainability. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 12(6), pp. 1091–1100

Tandapany, R., 2020. Cashless society: Is It Possible for Everyone? Malaysiakini. Available

online at https://www.malaysiakini.com/letters/549164, Accessed on November 3,

2020

Ton, J.T., 2018. Judith Butler’s Notion of Gender Performativity.

Master’s Thesis, Graduate Program, Utrecht University Repository

World Health Organisation (WHO), 2021. Ageing and health. World

Health Organisation. Available online at

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health, Accessed on

July 10, 2022

World Health Organisation (WHO), n.d. Gender and Health. World

Health Organisation. Available online at https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1,

Accessed on April 20, 2022

Wong, C.Y., Ibrahim, R., Aizan Hamid, T., Mansor, E.I., 2018.

Mismatch between Older Adults’ Expectation and Smartphone User Interface. Malaysian

Journal of Computing, Volume 3(2), pp. 138–153

Wong, C.Y., Ibrahim, R., Aizan Hamid, T., Mansor, E.I., 2020.

Measuring Expectation for an Affordance Gap on a Smartphone User Interface and Its

Usage among Older Adults. Human Technology, Volume 16(1), pp. 6–34

World Economic Forum, 2021. Global Gender Gap Report 2021.

Report by the World Economic Forum, Cologny/Geneva, Switzerland

Yin, R.K., 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design

and Methods. 6th Edition. COSMOS Corporation, SAGE Publication, Inc