A Reconstruction Study on the 30-Wheeler Ceremonial Vehicle of Melaka Sultanate

Corresponding email: fauzan.mustaffa@mmu.edu.my

Published at : 03 Nov 2022

Volume : IJtech

Vol 13, No 6 (2022)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i6.5878

Mustaffa, F., Abidin, M.I.Z., Othman, M.F., 2022. A Reconstruction Study on the 30-Wheeler Ceremonial Vehicle of Melaka Sultanate. International Journal of Technology. Volume 13(6), pp. 1354-1368

| Fauzan Mustaffa | Faculty of Creative Multimedia, Multimedia University, 63100 Cyberjaya, Selangor, Malaysia |

| Mohamad Izani Zainal Abidin | Faculty of Applied Media, Higher College of Technology, Po box 25026 Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates |

| Muhammed Fauzi Othman | Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 Skudai, Johor, Malaysia |

Portuguese historical sources mentioned the

existence of a 30-wheeler ceremonial vehicle that belonged to the Sultan of

Melaka embedded in the 1511 war narrative. This report documented several measurements on the vehicle

but was rarely analyzed academically. This project's fundamental goal was to

reconstruct the arguably historical and extinct vehicle. It employed narrative

analysis in dealing with textual clues involving components and measurements of

the vehicle. Moreover, each component was carefully scrutinized as an

integrated whole. Visual anthropological research was applied to cross-compare

related historical visuals involving a Dutch Melaka sketch of a similar concept

vehicle. It also investigates the route to where the vehicle was driven which

has direct and indirect implications on its design. Subsequently, design thinking was applied to

pursue the design process to achieve the research’s reconstruction objective.

The analysis and design process of the reconstruction consider the context in

which the vehicle was used. According to the findings of this study, this Malay

Sultanate ancient vehicle has a unique form and has complex mechanical design

and maneuvering capability. Nevertheless, it is not comparable to the Malay

royal vehicles that existed during the Dutch Melaka period. The study has

limitations since it relies on English translation in dealing with ancient

Portuguese texts. The long-term goal of this reconstruction study is to promote

historical Melaka identity tourism, which is in line with SDGs 8.9 and 11.4.

30-wheeler ceremonial vehicles; 15th century Melaka sultanate; Melaka sultanate land vehicle; Melaka sultanate technology; Melaka sultanate

The fifteen-century kingdom of Melaka Sultanate harbor city

is often regarded as the height of Malay Muslim civilization with its glorious

achievements in administration, economic and physical construct (Mokhtar & Kosman, 2019). By nature, the

native of Melaka Sultanate was well known to be a maritime society that

centered its life on the water and demonstrated collective expertise in boat

making and shipbuilding (Abdullah, 2015).

Many scholars have extensively studied Melaka Sultanate’s marine structures and

water vehicle technology.

A wheeled land vehicle as part of the Melaka Sultanate

royal customary inventory is a remarkable feat but is rarely discussed. A week

before the 1511 war broke up, the wheeled vehicle was reported to have been

used in a parade to celebrate the royal wedding couple of the king of Pahang

and the princess of Melaka in a procession through the city (Birch, 2010).

A Portuguese general, Alfonso de Albuquerque’s reported his eyewitness

account could offer us an authentic description of the land vehicle technology

of the Melaka Sultanate. Seemingly impressed, Alfonso, in his report, decided

to give a well-written description of what he saw in a manner that glorifies

it. In a paragraph writing, Alfonso described the ceremonial vehicle as

follows:

“Here was burnt a wooden house, of very large size and very

well built with joiners’ work, about thirty palms breadth solid timber all

inlaid with gold, built up on thirty wheels, every one of which was as large as

hogshead, and it had s spire, which was the finishing-point of the building of

great height, covered with silken flags and the whole of it hung with very rich

silken stuffs, for it had been prepared for the reception of the king of Pao

(Pahang) and his bride, the daughter of the king of Malacca, who were to make

their entry through the city with great blowing trumpets and festivities” (Birch,

2010).

This detailed account by Alfonso clearly describes the

components, dimensions, and nature of Melaka Sultanate's heritage's great

vehicle. This allows a reconstruction study and a glimpse into the lost 15th-century

ancient native Malay technology and civilization. This is aligned with a

scholarly study that heritage constructs must be given priority in developing

nation-building to ensure the survival of cultural heritage for future

generations (Kayan et al., 2018). In

addition, such reconstruction can facilitate activities that can enhance

identity tourism experiences; as responses to expectations from tourists (Widaningrum et al., 2020). The reconstruction of

the 30-wheeler ceremonial vehicles could contribute to different dynamics of

digital heritage (relative to static heritage buildings) because it is a moving

object full of royal customs. The emergence of innovative solutions in

developing virtual tours to put cultures alive can improve virtual tours'

design to optimize the tourism experience (Drianda

et al., 2021).

It is interesting to see how ancient architectural

discourse correlates with the underlying idea of humanity's attempt at the

structural construct. A renowned ancient Roman architect and engineer

identified a well-designed architectural construct must exhibit three

qualities; ‘firmitatis,’ ‘utilitatis’ and ‘venustatis’ that are stability,

utility, and beauty, also known as Vitruvian virtues or the Vitruvian Triad (Vitruvius, 2009). According to him, the human

construct is a reflection of imitation of nature, the same it is with birds and

bees building their nests (Vitruvius, 2009).

Similarly, the earliest Malay builders understood how to make a comfortable

dwelling that fulfills its purpose as a location in response to nature (Bahauddin & Abdullah, 2008). Some of the

traditional Malay architecture directly took inspiration from natural metaphorical

forms like ‘bumbung gajah menyusu’ or ‘the suckling elephant roof’ and ‘kayu

belalang bersagi’ ‘grasshopper form or octagonal timber logs’; this is not to

mention natural wood carving motif which connects directly to the quality of

‘venustatis’ (beauty).

Vitruvius’s principles on machines were seemingly

influenced by commerce activities, such as the engineering idea of the

articulation of mechanical elements like hoists, cranes, and pulleys, as well

as war machines such as ballistae, catapults, and siege engines (Vitruvius, 2009) which brings back to the

qualities of ‘firmitatis’ (stability), utilitatis (utility). One may deeply

ponder when reading Alfonso’s description of the 1511 war narrative that “…the

king of Malaca came up mounted upon an elephant…with wooden castles containing

many war-like engine…” (Birch, 2010). In the

15th century, Leonardo da Vinci seemed to revitalize the discourse of Vitruvius

in his glorification of the Vitruvian Man inscribed in the circle and the

square, which reflect the fundamental human-architectural proportion. Little is

known if traces of a shared European Renaissance period discourse responded to

by the Malay world reflected on such an unprecedented innovation of a

30-wheeler ceremonial vehicle.

This architectural artistry seems to relate well with the

argument that the material world constantly converses with humanity through its

resistance, ambiguity, and tendency to change in response to external

circumstances (Sennett, 2008). The

enlightened can engage in this conversation and develop an "intelligent

hand." Instead of following the "common foundation of talents,"

people frequently exaggerate "small disparities in degree into vast

distinctions in kind" to legitimize their elite institutions (Sennett, 2008).

This study used a qualitative approach and engaged in investigative research, techniques, and methods to unearth hidden or obscure information that helps develop a more comprehensive picture of a historical object under investigation (Layder, 2018). In other words, the historical record is the basis for this study's understanding (Layder, 2018). This encouraged the researcher to look at and undertake data collection on accounts primarily from Portuguese, supported by Malay, Dutch, and the Middle East documents. Thus, this research was molded by the nature and character of document analysis, where documents were given voice and interpreted, and meaning was put into perspective to build an understanding around and on the targeted historical object. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between overall data collection and data analysis techniques for the project.

Figure 1 Overall Data

Collection and Data Analysis Strategy for the Study

The narrative analysis framework (Czarniawska, 2004) was used in this research to

investigate, choose, examine, and analyze descriptive clues that could shed

light on the subject at hand. The study began with identifying the vehicle,

followed by a part-by-part focus analysis of Alfonso’s paragraph-long

description. This study pays attention to and relies on the credibility of

sources and information pertinent to the vehicle's form, components, and

measures. Wherever necessary, this research puts each description into context

by employing other related supporting documents, be it textual or visual, to

comprehensively reveal an idea of the vehicle.

In the study, a visual anthropological

analysis framework (Collier, 2004) was also

used to cross-compare and precede related archived visuals involving a Dutch

Melaka period sketch on a seemingly similar royal vehicle. This section also

brings into the discussion selected ancient Melaka municipal plans to explore

the possible route the vehicle traveled that best fit the description. The

character of the route was investigated as it provides more clues impacting the

design of the ceremonial vehicle.

Finally, the design-thinking framework (Ambrose & Harris, 2010) was utilized to study

design processes to achieve the research’s reconstruction objective. The

analysis and design process of reconstruction also pays attention to the

context of how the vehicle was put to work. This study built the case of the

reconstruction part by part and discussed as an integrated whole until an

interpretative 3-dimensional impression of the ceremonial vehicle is built.

This includes the basic mechanical look of the vehicle.

Findings from Narrative Analysis

Even though ‘The Commentaries of the

great Afonso de' Albuquerque was written by his son, Brás de Albuquerque, the

book was produced based on his father’s diary and copies of letters to the king

of Portugal (Earle & Villiers, 1990).

The strength of Alfonso’s sources lies in the fact that he was literally

present in Melaka, witnessing firsthand the Melaka Sultanate’s state of affairs

while still in operation. Alfonso arrived at Melaka harbor on the 1st of July

1511 (Loureiro, 2008), and the Melaka

Sultanate- Portuguese war broke up on the 25th of July 1511 (Earle & Villiers, 1990). Within this period,

there were peace negotiations between the two parties (Correia, 2012), while

Alfonso himself was exposed and witnessed Melaka’s daily life for about 24

days. Alfonso himself may not have stepped his foot on Melaka soil, but at that

time, Melaka’s shoreline was close to the city's main streets. Alfonso

witnessed the 30-wheeler ceremonial vehicles utilized

in a royal parade. Based on the 1511 war narrative, this ceremonial vehicle was

burned in the royal compound (Birch, 2010).

However, before the war, the ceremonial vehicle participated in a royal parade

in the city (of Upeh) during a royal wedding reception. According to this

description, the vehicle would have to cross the city’s main bridge and travel

along the primary streets of Upeh (the main vicinity a cross Melaka river)

before returning to the royal compound.

Alfonso described that the ceremonial

vehicle was mainly made of wood. Hence, in addition to its basic construction,

this design would include wooden accessories and embellishments. It's

noteworthy how Alfonso refers to the vehicle as a ‘house’ and describes it as

being a ‘very large size’ at about “thirty palms in breadth or seven and a half

feet in width.” We view this as the ‘X’ factor, which has a discerning

influence that makes the vehicle looks ‘very large’ despite its basic size; so

to speak, a space comparable to the size of a small ‘room’ but with the look of

a ‘house.’ However, the length of this vehicle was not disclosed.

According to the text, the vehicle's

architectural artistry was marvelously superb. Because it was made of solid

wood, the structure was relatively weighty. To be pulled in a parade through

the city, a vehicle of this weight will almost certainly demand considerable

energy. More clues related to the route taken based on the description provides

important context benefiting this study and will be discussed in the visual

anthropological section of this paper. By the look, it appears that this

ceremonial vehicle appeared beautifully ornamented with wood carving

designs “…inlaid with gold”.

Another impressive aspect of this

ceremonial vehicle is that it was built upon thirty wheels; Alfonso uses

‘hogshead’ as a reference to describe the size of each wheel; a size which the

15th-century English term 'hoggers hede’ referred to as a unit of

measurement equivalent to 63 gallons barrel (Difford,

n.d.); in a context which generic western’s standard size of hogshead is

thirty inches in diameter (Hogshead, n.d.).

Based on the description, the vehicle

has complete roofing as a tall tapering spire. However, this study considers

that the vehicle's floor dimension significantly influences its overall form, a

sub-case that will be examined during the design process. Based on Alfonso’s

expression, the spire of the vehicle was significantly tall, although no

estimated measure was given on its height. On the other hand, this vehicle must

cross the Sultanate gate (in Malay called ‘gerbang’), which typically has a top

enclosure. As such, a practical measure of the height of the spire will be

discussed.

This vehicle was described as being

‘covered’ with silken fabric. It was also mentioned that the silken fabric was

particularly flagged. This study suggests that they would be no other than the

Melaka flags themselves. Based on the text, those flags were positioned at two

places: i) at the tapering spire and ii) at the vehicle's body. The use of the

words ‘flags’, could indicate that more than one flag was installed at its

spire. All body façades in between the pillars of the vehicle would also be

covered with silken flags and perhaps can be unfolded like curtains. This is

following the description that “…the whole of it hung with very rich silken

stuff”. However, there is no reference to what symbol and color were used on

the Melaka Sultanate flag available in the public domain.

By the description, the march in which

the vehicle participated was ceremonial. The royal bride and groom whom the

vehicle carries were celebrated and paraded through the city accompanied by

full royal customaries, which included the “…great blowing trumpets and

festivities”. The study views this occasion as a shared culture between the

Melaka ruler and the cosmopolitan societies of the Melaka Sultanate. This

apparently suggests that the royal possession involving the 30-wheeler vehicles

is not a one-off occasion but happened numerous times.

A medieval Muslim traveler, Ibn Battuta,

who visited Melaka in 1345 (Gibb, 2005), mentioned elephants were commonly used to

carry loads during the Melaka Sultanate era. He also described Melaka fortress

city (royal compound) at that time were constructed of hewn stone with a gate

wide enough for three elephants to walk through. This study sees that the use of elephants was

the reason why the gate of the Melaka Sultanate fortress was apparently wide.

The size of the gate limits the design of the ceremonial vehicle. On the other

hand, the Malay Annals (Ahmad, 2010) mentioned

that the royal compound has seven gates from the main entrance to the Sultan’s

palace, beside consistent with the use of elephants involving the royal parade.

4. Findings

from Visual Anthropological Analysis

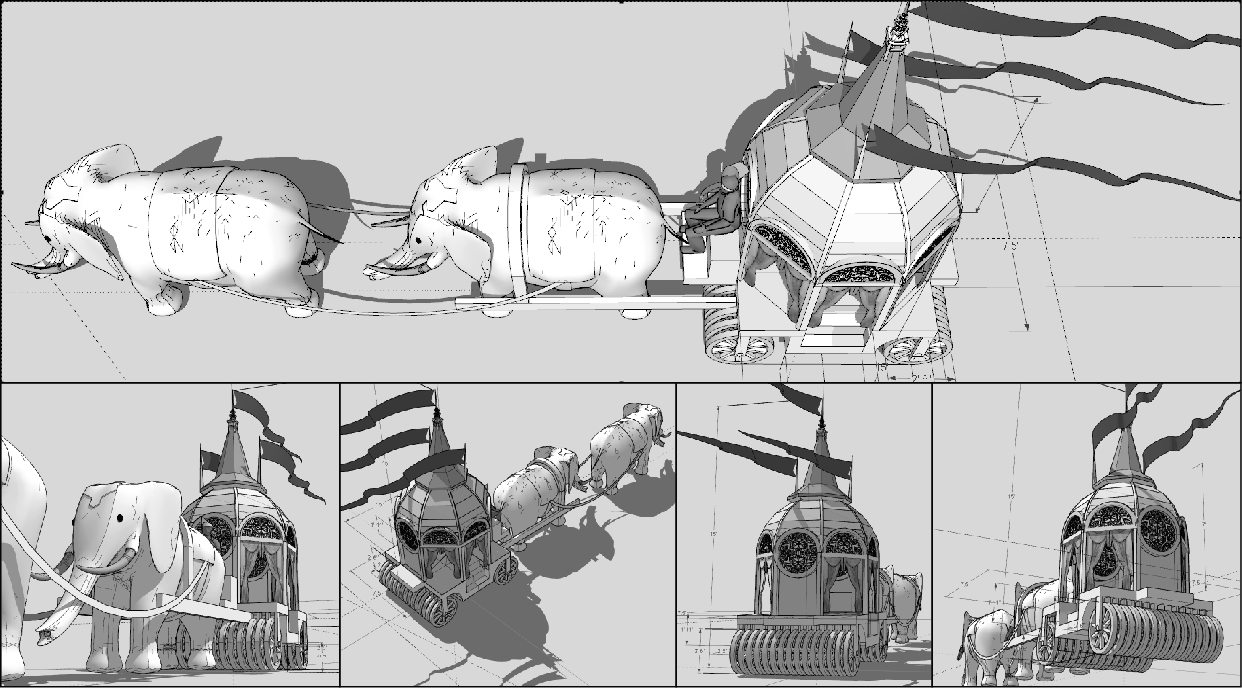

Figure 1 depicts a royal parade on a 30-wheeler ceremonial vehicle during the Dutch period. Figure 1 is a redrawn from an engraved artwork originally inscribed ‘Carosese Royal de trente roues tire par douze Elephans’ (meaning “The Thirty-wheeler Royal Carriage pulled by twelve Elephants’) by Pierre van der Aa in the early 1700s (Moore, 2004). Obviously, this ceremonial vehicle is by far too huge in comparison to the one described by Alfonso. Based on the sketch, the 30 wheels were distributed in at least four rows. Its wheels are relatively comparable to the size of a hogshead.

Figure 2 A redrawn of

thirty-wheeler royal ceremonial vehicle during Dutch Melaka (the Early

1700s)(Source: Moore (2004), p23)

The tower on top of the main structure

does not match the expression of a tall tapering spire. There is no indication

of the fabrics covering the structure are flagged. It is almost impossible that

a vehicle this large can pass through a bridge. It is unclear why a Malay royal

ceremonial vehicle rooted in Melaka Sultanate tradition was not built in its

original form and dimensions during the Dutch Melaka period. This is especially

appearing in the depiction of the vehicle attempting to equal the Melaka

Sultanate royal vehicle in the context of its 30 wheels. However, it is

important to note that the above ceremonial vehicle and the one from Melaka

Sultanate are from different eras separated by nearly 200 hundred years.

Another aspect that this study can learn from the sketch is that such a vehicle

would justifiably be pulled by elephants.

Visualizing the route of the 30-wheeler ceremonial vehicles based on

Alfonso’s narrative is not something inconceivable, even though there is no

municipal plan for the city of Upeh in reference to the Sultanate era. The

above municipal plans (figure 3(a), (b), (c), and (d)) are brought into the

study to trace the route taken by the ceremonial vehicle through the city. In

general, the municipality of Melaka during the Sultanate era can be divided

into two parts: i) the royal compound and ii) the cosmopolitan city of

Upeh. The vehicle departed from the

royal compound and paraded throughout the city of Upeh before returning to the

palace. The city of Upeh, also known as

the cosmopolitan city or the emporium of the Melaka Sultanate, was segregated

into territorial settlements of traders based on local and foreign ethnic

groups led by designated Syahbandars or harbourmasters from each ethnicity.

Portuguese appears to have retained the main structural municipality traced

down to Melaka Sultanate tradition.

Figure 3 Mapping route of the vehicle at the three-cornered primary street of

Upeh

Figure 3(a) Portuguese Melaka

1568 (Source: Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro)

Figure 3(b) Portuguese Melaka

(1613) (Source: “Planta da cidade e povoacoens de Malaca”, Declaram de Malacca,

1613, Bibliotheque Royale, Bruxelles)

Figure 3(c) Dutch Melaka, 1791 (Source: The Malaysia

Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1985)

Figure 3(a) illustrates the

redrawn municipal plan of Melaka created by an anonymous Portuguese

cartographer living in the city in 1568 (Loureiro,

2008). It is one of the closest

municipal plans to the Melaka Sultanate period. It contains a detailed

impression of Portuguese Melaka city that “…is unmatched by other known

depictions of the city” (Manguin, 1988). On the other hand, figure 3(b) declares information

on the main network of streets and territories of ethnic’s societies (Malay,

Chinese, Indian, and Java) preserved in their original names in the tradition

of the Melaka Sultanate. Both figures 3(a) and (b) combined provide crucial

contextual information in tracing basic municipalities in the rule of Melaka

Sultanate, especially the primary 3-cornered streets, which enlightened the

route taken by the ceremonial vehicle in this study.

According

to Alfonso, warehouses in Chinese and Indian merchant settlements were

unaffected since they cooperated with Portuguese administration during and

after the 1511 war. Although Malay was perceived as the enemy by the Portuguese

during the 1511 war, their parameter seems to remain in its original name

(Kampung Bendahara or Bendahara Village), as reflected in figure 3(b), where

the house of Bendahara can be seen in figure 3(a). So do Javanese merchants, in

whom the Portuguese still had an interest after capturing Melaka in 1511 (Birch, 2010), with designated

parameters likely remained as Java settlement. It is baseless to imagine that

Chinese, Indian, Java, and local settlements were switched during Portuguese

Melaka because each settlements contains properties based on ethnic and

cultural preferences. Therefore, streets and territorial parameters in the

trading city of Upeh had a direct tradition of the Melaka Sultanate period, as

we can approximate in the Portuguese Melaka municipal impression of 1658 as

reflected in figure 3(a).

Primary streets are

structural to the municipality of a city and cannot easily be restructured

because there are buildings on both sides. The drastic change of such primary

streets means demolishing buildings along them. Figure 3(c) (during Dutch’s

Melaka) and (d) (modern Malaysian Melaka) depicting the preservation of the

three-cornered streets is a testimony of the perspective. In conclusion, the

three-cornered streets already existed during the Melaka Sultanate in an approximation

of figure 3(a), (b), (c), and (d); which demonstrate the consistent pattern of

the three-cornered street of Upeh during Portuguese Melaka, Dutch Melaka period

and Malaysian Melaka at present.

5. Summary of the

Narrative and Visual Anthropological Analysis

However, apart from the separate narrative and visual anthropological analyses, the fusion of both provides clues that extend the idea of the ceremonial vehicle design. As displayed in Figure 4, these clues helped the vehicle design research, which had to overcome at least six challenges as the parades moved along the described route.

Figure 4 Challenges of the route that

provide clues on the design of the vehicle.

The Sultanate Melaka palace was located

at the top of Melaka Hill. The royal compound has broader boundaries, including

the foothill and surrounding area. Based on the 1511 war narrative, it is

unclear how close the vehicle was to the palace when it was parked, took off or

burned down. Therefore, the challenge as the vehicle took off from the royal

compound is dismissed. The total size of this vehicle (which includes its

ornamental constructs) was supposed to be conducive enough to pass through the

sultanate gate, which according to Ibn Battuta (Gibb,

2005), was big enough for three elephants to go through. Therefore, the

open width of the gate is estimated at 15 feet. The study also suggested that

the vehicle’s height should not exceed 15 feet as ancient royal Malay gates (in

Malay called ‘gerbang’) typically also have a top enclosure, commonly in the

form of an arch.

This study also suggests that the

vehicle's reconstruction be scaled appropriately; Alfonso's description of a

wooden house, of enormous proportions can be seen as a perceptive expression.

In reality, the vehicle has the space of a 'room' but the appearance of a

'house.' The ceremonial vehicle, however, is hefty despite being made of solid

hardwood of small size.

As

the vehicle passed through the Melaka River, it must escalate a tall Sultanate

bridge. In a separate study, the diagonal deck of the bridge is estimated at 15

degrees (Mustaffa & Othman, 2021). This

factor has implications for the distribution of the vehicle's 30- wheels, which

will be discussed later. The escalation and de-escalation of the vehicle on the

bridge requires a justifiable force of energy, especially given Alfonso’s

description that it was constructed using solid timber. This study also

suggests that such a crafted royal celebrative vehicle should be decorated with

wood curving motifs. This adds up to the overall weight of the vehicle. The

means to pull the ceremonial vehicle is also considered part of its

reconstruction in this study to be considered in the design process.

Based on Alfonso’s description, the

ceremonial vehicle would have journeyed quite a distance from the royal

compound, passing through the Sultanate primary gate, crossing the Sultanate

bridge, and moving along the primary streets. As the vehicle reached

Bendahara's house, as seen in figure 5(a), it turned right, passing through the

designated Malay trading zone before reaching the Chinese and Javanese trading

territories. Finally, the vehicle took the left turn back to the Sultanate

bridge and parked at the royal compound where it was last seen.

Taking the journey that long would have

been an enormous feat for this ancient vehicle, especially in passing up and

down a tall bridge and maneuvering at the sharp three-cornered primary streets

of Upeh. The design process should consider the vehicle's fundamental

structural and mechanical aspects. The main three-cornered streets of Upeh require the

vehicle to make multiple turns which is even quite challenging for a modern-day

vehicle.

5. Findings of the Design

Process

The design process took two months to digest, experiment, and assemble every component based on the description and analysis. The toughest part was the distribution of 30 wheels. It is easy to assume the distribution of the wheels were evenly in 5 rows (6 wheels in each row) or 3 rows (10 wheels in each row). However, the ceremonial vehicle had been traced to pass the Sultanate bridge, which was relatively high. The bridge was elevated to allow medium size water traffic to pass underneath it. Figure 5 portrays a 2D ‘simulation test’ on a design problem that governs the design thinking concerning the distribution of 30 wheels in the context of a transitional point on the Sultanate bridge.

Figure 5 Test of the vehicle at the

transition point between the diagonal and horizontal bridge’s deck at 15 °

The degree of the bridge’s diagonal deck

in other studies was suggested at 15 degrees (Mustaffa

& Othman, 2021). This creates an intricate design problem for the

vehicle to pass through at the transition point between the diagonal and

horizontal deck. Based on the ‘simulation test,’ wheeled vehicle with more than

two rows has a significant problem passing this part of the bridge. In that

context, the vehicle must be lifted, followed by the crashing of the frontal

part as it crosses the transition point at the horizontal deck. It is important

to note that this vehicle was designed to carry royal figures on ceremonial

occasions. In the practice of royal tradition, such severe architectural

defects are unlikely to be accepted. After careful consideration, this study

cannot but suggest that the arrangement of the vehicle’s wheels should only

consist of two rows with 15 wheels on each row.

Built on solid timber and to satisfy its descriptions, this ceremonial vehicle is relatively heavy. The Sultanate bridge, where the ceremonial vehicle passed through, possesses an unavoidable design problem but, in a way, provided insight into its capability of it. The vehicle must utilize considerable force to climb the bridge, and the Dutch Melaka precedent provide the clue on the use of elephants to solve this problem.

Figure 6 Alternative force used as

breaking mechanism to slow down the vehicle at the bridge’s slope

To de-escalate on the other side of the bridge, the ceremonial vehicle also must use tremendous force as a breaking mechanism to slow down. Not only the Sultanate bridge contributes to the understanding of this vehicle. The analysis of this vehicle also contributes to the understanding of the bridge. To the least, we can learn that the Sultanate bridge is not just a pedestrian bridge.

Figure 7 The proposed basic wheel

mechanism and overall 15 wheels in a row

Figure 7(a) demonstrates the proposed

basic single-wheel mechanism. Concerning Alfonso's phrase 'hogshead' (and in

cross-referencing to the 15th century generic western's standard), a single

wheel has a diameter of 30 inches. The structure of the wheel is held by 8 (1”

x 1”) spokes mounted deep into a 9” diameter boxing hup (3” tick). Figure 7(a)

shows a 3” diameter axle bar ready to be inserted through the 15 wheels and 14

interval vertical bars. These vertical bars are mounted deep into the

structural beam of the vehicle. Metal washers are proposed between all vertical

bars and boxing hup of each wheel to resist friction. In this study, wooden

nuts are recommended as a locking mechanism to hold strong wooden axle bars,

thereby stabilizing their relationship with the wheels and vertical bar. Figure

7(b) demonstrates a single polar of the wheel, while figure 7(c) depicts the

collective looks of all 15 wheels’ mechanisms when fixed.

Figure 8 Basic mechanical interpretation

for the vehicle to make a 45-degree maneuver

Making the case of the ceremonial vehicle’s mechanical

in reflection of its extreme maneuvering capability (at the

sharp three-cornered streets) is difficult. First, there is no precedent of

animal cart that belongs to the ancient Malay world, which has 2 rows of

wheels. This is not to mention the fact that precedent on 30-wheeler vehicles

seems unobtainable other than royal Malay of the Dutch Melaka period, which

does not make sense to perform a similar task to that of the Sultanate Melaka

era. Bullock cart in the tradition of Melaka or Malay world at large (which

survive until now) has only two wheels and arranged in one row, which makes it

easy to maneuver.

As such, the study moves forward in

experimenting with basic mechanical concepts relatively feasible for the

ancient native of Melaka. Figure 8(a) demonstrates the joiners’ work that

connects three central beams with the frontal beam in supporting its main

structure; at the same time, establishes its relationship with the beam that

holds the 15 wheels. A strong metal bar is ready to be plugged into a hole of

the frontal beam and penetrates deep into a second frontal beam which also acts

as an axle that enables the entire frontal wheels to make a turn. In between,

there is a metal plate to separate the two frontal beams to resist friction

when the ceremonial vehicle makes its turn. Figure 8(b) illustrates all of the

beams when joined, whereas figure 8(c) depicts the vehicle's structural

mechanism when making a 45-degree turn. According to the study, only the front

wheel can turn, while the back wheels always align with the vehicle's body.

Another significant part of

reconstruction is the form of the ceremonial vehicle, which contributes to the

overall appearance. The study decided that it makes more sense to revert to the

essence of the precedent out of all sketches done on the main form of the

vehicle. Regardless of the differences reflected by the ceremonial vehicle

during the Dutch Melaka period, this study is from the perspective of seeing it

as being the tradition of the Melaka Sultanate. Both constructs can be seen as

‘30 wheeler ceremonial vehicle’. As such, the study took the strongest design

essence from the vehicle of the Dutch Melaka period as a reflection of that of

the Melaka Sultanate. This refers to the curve arches which connect between

pillars as reflected in figure 9

(a) and (b). To curve a wooden structure may seem quite challenging for

the ancient builder. Nonetheless, considering the Malay maritime civilization's

history of boat construction and shipbuilding, such a challenge is nothing

extraordinary.

Figure 9 The main form of the ceremonial

vehicle based on the precedent

To reconstruct the form, the study needs

to determine the floor dimension of the vehicle. Alfonso only mentions its

width, but the length of it is still unspecified. If the length of the vehicle

is more than its width, Alfonso would likely have provided the measurements

since he generously tried to furnish the details. The fact that he only

provided the estimated measurements of the vehicle’s width and did not border

with its length could be because it is the same anyway. However, the study

continued by putting the vehicle to the test through the Sultanate bridge,

which it has been traced to have crossed through. Based on the test, if the

length of the vehicle is too long, it will affect the distance arrangement of

the frontal and back wheels, and that could cause the middle part underneath

the vehicle stuck at the transition point between the diagonal and horizontal

deck, as demonstrated in figure 5(c). To avoid this problem and in the spirit

of Alfonso’s way of describing, the study suggested that the width and length

of the vehicle are the same at 7.5 feet. In other words, the basic floor of

this vehicle’s structure is square.

Figure 10 Reconstruction of the ceremonial

vehicle

Besides

taking off from the declared precedence, the study also adheres to the idea

that the construct was a royal ceremonial vehicle. A special construction

requires a special material. There was a special crafted timber mentioned in

Malay Annals in the form of ‘belalang bersagi’ (Ahmad,

2010), about the form of grasshopper interpreted as octagonal solid logs

as seen in figure 10(a). With these solid octagonal logs as columns, the main

structure of the ceremonial vehicle will take the form of an octagonal prism,

reflected in figure 10(b). Curve timber arches continue from these columns and,

at the same time, influence the form of its roofing, as can be seen in figure

10(c). Wooden planks were shaped and filled up the structural frame, and

completed the form of a dome as reflected in figure 10(e).

Wherever appropriate, the body of the vehicle was given the traditional Melaka wood curving motifs, as seen in figure 11(a). The study also suggested that the frontal façade of the vehicle is covered. Otherwise, the royal figure will face the back of the driver and worst, the back of the elephant, which is quite tall (See figure 11(a)). The frontal and rear façade of the vehicle also had an enclosure wall to provide backrest for 2 seats and cushion fittings for the royal couple to lean on, as reflected in figure 11(a) and (b). The structure, which takes the form of an octagonal prism, not only influences the 8-sided façade of the roofing but also the tapering spire, as reflected in figure 11(c) and (d). The tapering spire is furnished with three silken flags, as indicated by the plural usage of the term "flags" in Alfonso's description. Figure 11 illustrates how a thin silken cloth can help Melaka Sultanate banners fly gloriously when the wind blows (d). These silken fabric flags are also employed to furnish an open structural façade of the ceremonial vehicle, which may be opened like curtains, as shown in figure 11(e).

Figure 11 The integration of wood curving motif and features on the ceremonial vehicle

6. Discussion

This study uncovered an extinct

Melaka Sultanate native innovation. The fact that there seems to be no

precedent for 30-wheeler vehicles in another part of the world indicates that

it was a local idea. A Portuguese

general seems impressed with the artistry

of the ceremonial vehicle and provides his account in a way that

glorifies it. The fact that the vehicle was burned at the royal compound but

earlier paraded across the city enables the researchers to conclude that it had

passed through the tall Sultanate bridge and other obstacles, providing more clues about its design. The narrative

analysis benefits the study of the nature, componential and dimensional aspects

of the ceremonial vehicle. In contrast, the visual anthropological analysis

provides precedence and puts the context of its journey centered on obstacles

which have implications for its design. Although described at length, there is

no way the study can make up the reconstruction only based on the text and

narrative analysis. The most challenging part was to arrange the distribution

of its 30 wheels without suitable precedence. Only the builders know why they

built a vehicle with 30 wheels. One thing is sure: it was designed to tackle a

specific problem.

The overall form of the vehicle is taken from the essence of precedent on similar Malay royal vehicles of the Dutch Melaka period but redesigned suitable to its relatively small scale. Structurally, its form is derived from special crafted timber logs mentioned in Malay Annals in the form of ‘belalang bersagi’; which makes up the overall octagonal prism. The wood curving motif was taken from Melaka tradition to satisfy the context of the description “…all inlaid with gold”. The historical description demonstrates that the royal parade involving the ceremonial vehicle was a shared cultural celebration that brought the royal family closer to various levels of society on the streets of Melaka. As such, it is more fitting that the parade optimized the reach of its societies. Based on the description, it is most appropriate that the parade occurred along the primary three-cornered street of Upeh. Consequently, this study also demonstrated that the ceremonial vehicle has an effective maneuvering capability and proposed a basic mechanism to enable it to perform its tasks. This study learned that Melaka Sultanate’s flag has more than one color from the 1511 war narrative (Birch, 2010), but this study still requires factual data or reference on the type of symbolism and its colors. Figure 12 below reflects the final 3D interpretative impression of the 30 wheeler ceremonial vehicle based on the idealism of the studies.

Figure 12 Final impression of the

30-wheeler ceremonial vehicle based on the idealism of the study

From the discussions above, we suggest

that this ceremonial vehicle has a high level of architectural craftsmanship

and a majestic look of a house despite its size in comparable space to a room

which reflects a magnificent feat of the Melaka Sultanate. This could be

inferred by the admiration and lengthy description furnished by Alfonso

himself. It is interesting to enquire about the aspects of the design thinking

behind the use of 30 wheels on a single vehicle. It may appear that the ancient

innovator of this vehicle struggled to find a better solution to increase the

collective strength of its wheels due to the rough textural surface of ancient

streets. This study can only suggest their basis and practical distribution

based on the obstacle it faced in passing a tall bridge. Due to its

sophistication, we conclude that this vehicle was not an ad-hoc apparatus,

instead was rooted in a symbolically shared cultural tradition between the

royal and the people of Melaka. It is also a tradition of kings in the past to

show off their might and technological feat. As Melaka is an international

marketplace, the Sultanate kingdom would find that it is critical to express

its magnificence. The paraded royal couple on this ceremonial vehicle was said

to have been accompanied “…with great blowing trumpets and festivities” likely

had occurred many times in the past. This would potentially bring the royal

family closer to various levels of society on the streets of Melaka. A Malay

proverb goes, “raja dan rakyat berpisah tiada,” meaning “the king will never be

separated from his subjects.”

Abdullah,

M.Y., 2015. Bicara Dunia Melayu: Tradisi Pelayaran Melayu (Talking about the

Malay World: Malay Shipping Traditions). Tradisi Pelayaran Melayu di

Jabatan Muzium Malaysia. Available online at

http://www.jmm.gov.my/files/ORANG%20 MELAYU%20DAN%20ALAM%20KELAUTAN.pdf

Ahmad,

A.S., 2010. Sulalatus Salatin Sejarah Melayu (Sulalatus Salatin Malay

History). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka

Ambrose,

G., Harris, P., 2010. Design Thinking. Switzerland: AVA Publishing SA

Bahauddin

A., Abdullah A., 2008. In Harmony with Nature–the Suckling Elephant House of

Malaysia. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, Volume

113, pp.137–147

Birch,

W.D.G., 2010. The Commentaries of the Great Alfonso D’Alboquerque, Second

Viceroy of India. London: Haklyut Society

Collier,

M., 2004. Approaches to Analysis in Visual Anthropology. (ed.). The

handbook of visual analysis. London: Sage

Correia,

C., 2012. In Which are Narrated the Great Deeds of Alfonso De Albuquerque, Lopo

Soares, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, D. Duarte de Menezes, D. Vasco da Gama and D.

Andrique de Menezes. (Part 2). Lendas da India. (Pintado, M.J., Trans). In

Portuguese Document on Malacca from 1509 to 1511, Pintado, M.J. (ed.) 2012,

Kuala Lumpur: National Archives of Malaysia

Czarniawska,

B., 2004. Narratives in Social

Science Research. London: SAGE Publications

Difford,

S., n.d. “Casks –barrel, butt, puncheon, pipe, barrique, hogshead.” Available

online at

https://www.diffordsguide.com/encyclopedia/481/bws/casks-barrel-butt-punch

on-pipe-barriquehogshead

Drianda,

R.P., Kesuma, M., Lestari, N.A.R., 2021. The Future of Post-COVID-19 Urban

Tourism: Understanding the Experiences of Indonesian Hallyu Consumers of

South Korean Virtual Tourism. International Journal of Technology, Volume

12(5), pp. 989–999

Earle,

T.F., Villiers, J., 1990. Albuquerque, Caesar of the East: Selected Texts by

Afonso de Albuquerque and His Son. England: Aris & Phillips

Gibb,

H.A.R., 2005. Ibn Battuta travels in Asia and Africa. London: Routledge

& Kegan Paul Ltd

Hogshead,

n.d.. Wikipedia. Available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hogshead

#cite_note-2

Kayan,

B.A., Halim, I.A., Mahmud, N.S., 2018. Green Maintenance for Heritage

Buildings: An Appraisal Approach for St Paul’s Church in Melaka, Malaysia. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 9(7), pp. 1415–1428

Layder,

D., 2018. Investigative Research: Theory and Practice. London: SAGE

Publications Ltd

Loureiro,

R.M., 2008. Historical Notes on the Portuguese Fortress of Malacca (1511-1641).

Revista de Cultura, Volume 27, pp. 78–95

Manguin,

P.Y., 1988. Of Fortress and Galleys: The 1568 Acehnese Siege of Melaka,

after a Contemporary “Bird’s-eye View.” In Modern Asian Studies. United

Kingdom: Cambridge University Press

Mokhtar,

N.A., Kosman K.A., 2019. Melaka Malay City before 1511 was based on Portuguese

Sketches. Asia Proceedings of Social Sciences, Volume 4 (2), pp 136–138

Moore,

W.K., 2004. Malaysia a Pictorial History 1400-2004. Kuala Lumpur:

Archipelago Press

Mustaffa,

F., Othman, M.F., 2021. Creative Interpretation as Basis of a Historical

Building Reconstruction: A Case Study of Melaka Sultanate Bridge. Research

Innovation Commercialization & Entrepreneurship Showcase. Cyberjaya: MMU

Press

Sennett,

R., 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven & London: Yale University Press

Vitruvius,

2009. The Ten Books on Architecture. United States: BiblioLife

Widaningrum,

D.L., Surjandari, I., Sudiana, D., 2020. Analyzing Land-Use Changes in Tourism

Development Area: A Case Study of Cultural World Heritage Sites in Java Island,

Indonesia. International Journal of Technology, Volume 11(4), pp.

688–697