An Analysis of End-of-Life Vehicle Management in Indonesia from the Perspectives of Regulation and Social Opinion

Corresponding email: rizq001@brin.go.id

Published at : 09 May 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 3 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i3.5639

Sitinjak, C., Ismail, R., Fajar, R., Bantu, E., Shalahuddin, L., Yubaidah, S., Simanullang, W.F., Simic, V., 2023. An Analysis of End-of-Life Vehicle Management in Indonesia from the Perspectives of Regulation and Social Opinion. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(3), pp. 474-483

| Charli Sitinjak | 1. Faculty of Psychology, Esa Unggul University, West Jakarta, Special Capital Region of Jakarta 11510, Indonesia. 2. Centre for Research in Psychology and Human Well-Being (PSiTra), Faculty of Socia |

| Rozmi Ismail | Centre for Research in Psychology and Human Well-Being (PSiTra), Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Selangor, Malaysia |

| Rizqon Fajar | Research Centre for Transportation Technology, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta 10340, Indonesia |

| Edward Bantu | Department of Social Work & Social Administration, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Kabale University, Plot 346 Block 3 Kikungiri Hill, Kabale P.O. Box 317, Uganda |

| Lukman Shalahuddin | Research Centre for Transportation Technology, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta 10340, Indonesia |

| Siti Yubaidah | Research Centre for Energy Conversion and Conservation, National Research and Innovation Agency, Jakarta 10340, Indonesia |

| Wiyanti Fransisca Simanullang | 1. Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Widya Mandala Surabaya Catholic University, Surabaya 60112, Indonesia, 2. Research Centre for Chemistry, National Research, and Innovati |

| Vladimir Simic | University of Belgrade, Faculty of Transport and Traffic Engineering, Vojvode Stepe 305, 11010 Belgrade, Serbia |

The huge automotive

industry in Indonesia has had a major impact on the environment and health

caused by ELV. An ELV is a vehicle that has reached the end of life due to age

or cannot be reused because of accidents and high repair costs. The absence of

procedures and laws in Indonesia related to the driving of this vehicle

resulted in the dismantling of ELV, and its management was carried out on an

original and unstructured basis. As a result, emissions of gases and toxic

substances are released into the environment. To reduce this problem,

implementing ELV management must be done. Implementing this ELV policy requires

the cooperation of all stakeholders (government, automotive industry, and the

community). Therefore, this study aims to understand the laws related to ELV

and its implementation in neighboring countries and explore public perceptions

of ELV management in Indonesia. The study was divided into two phases. The first

phase reviewed literature related to ELV laws, and the second was surveyed with

questionnaires. The results obtained from this research show that public

awareness and acceptance of the application of ELV are still very low. In

addition, the regulations that have been applied to check the feasibility of

vehicles are proven unable to cut down the number of old vehicles.

Awareness of ELV; ELV laws; End-of-life vehicles; Public acceptance

Indonesia is one of the developing countries with the second-largest

automotive industry sector in Southeast Asia. The automotive sector seems to be

a mainstay sector that

The lack of rules regarding the age of vehicles in Indonesia resulted in

the number of old vehicles still being used even though they look no longer fit

for use. In Indonesia, we often find vehicles over the age of 10 years that are

still used daily. This old vehicle is often called the ELV. ELV is a vehicle

that has reached the end of use and cannot be reused. ELV itself can be

classified into two, a naturally occurring ELV: is a vehicle that has reached

its end of use and has been damaged or un-reusable. This natural ELV can occur

if the vehicle has reached the age of over ten years. The second is premature

ELV: it occurs due to damage from accidents, fires, or destruction. In

addition, some vehicles cannot be reused because of economic problems such as

being unable to fix, not renewing vehicle taxes, and the dearth of spare parts in

the market (Harun et al., 2021).

ELV management should be carried out with special treatment. This is

done because ELV includes extremely dangerous garbage (Yano

et al., 2019). Oil, CFC, brake oil, tires, glass, and some other

materials are extremely dangerous if not managed properly. If this vehicle is

abandoned, it will hurt the community (D’Adamo,

Gastaldi, and Rosa, 2020; Yano et al., 2019). Such a release of

harmful gases from air conditioner liquids can degrade air quality and

ultimately affect the ozone layer. However, there are still many irresponsible

people leaving them alone on the side of the road, in parking lots, in the

police, and in residential areas (Mohamad-Ali et

al., 2018).

Besides contributing to poor air quality, considering that old vehicle

engines are less efficient in combustion, they will produce higher gas

emissions (hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide), and old cars are a major cause of

traffic accidents (Kassim et al., 2020; Ahuja

and Khanna, 2019; Jawi et al., 2016). According to the

Indonesian Ministry of Transportation, there will be 108,000 motor vehicle

accidents by 2020, with about 30% of those accidents caused by vehicles that

are no longer fit for use (BPS, 2020).

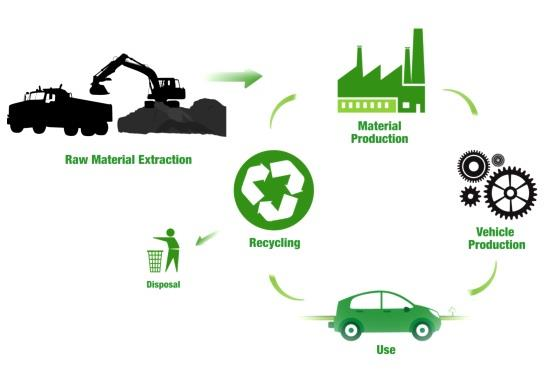

Looking at the negative impact that can be generated by ELV, the right

treatments must be done. The first step that must be considered is to clear

away all fluids, such as fuel, greasing oil, gear oil, and air conditioning

fluids. The second step is to eliminate other harmful components, such as

batteries and airbags (Sharma and Pandey, 2020). The last dismantling of the main

components of the mainframe is carried out. These components can be reused by

recycling. Once the entire process is complete, the remaining waste must be

taken to the car’s disposal and crushed (Santini et al., 2011).

As a country with huge automotive production, Indonesia has tried to

carry out regulations to cut down old vehicles, but it did not work. In 2009,

the government issued emissions test rules under UU 210 paragraph (1) of Law

number 22 of 2009. However, this rule cannot be implemented because there is no

socialization first. The government is again trying to reimpose the euro 4

standard in which the vehicle exhaust emission threshold is further tightened (MENLHK, 2017; DEPHUB, 2009). The government can

learn from the successful experience of the biodiesel program in Indonesia in

terms of conducting studies to support incentive policies and implementation

stages and involve stakeholders (Tjahjono

et al., 2021).

To realize ELV policies, the Indonesia government should accommodate the

public to take a role in reinforcing the policies regulating these old

vehicles. To ensure public understanding and acceptance of the ELV (old

vehicle) issue, we will distribute questionnaires to the public, government,

and non-governmental organizations. It will compare the results with developed

countries to compare people’s understanding of this regulation.

In Indonesia, there has not been special research referred to ELV. The novelty of this research is to present a mapping and analysis of the current condition of the vehicle owner community regarding knowledge of ELV and its level of acceptance. This research also examines regulations in other nations that have successfully addressed the ELV problem. Previous research has also indicated that examining public responses to ELV management can aid the government in determining the optimal framework for ELV management, particularly in developing nations such as Indonesia (Sitinjak et al., 2022).

Literature Review

ELV is a hazardous

waste and has the potential for environmental pollution if not managed properly

(Dabic-Miletic, Simic and Karagoz, 2021; Karagoz, Aydin and Simic, 2020). ELV itself is a

very large and dangerous household waste. ELV is very difficult to manage

because it has a very complex structure and varied composition. ELV is also a

waste that grows very quickly every year, but in some developing countries, ELV

is still not well considered. ELV is a vehicle that has reached the end of its

service life, which can be the result of an accident or the vehicle having been

used. The first is commonly referred to as ELV premature. The second type is

known as natural ELV. However, regardless of their origin, ELV is the end of

everything and must be managed by the logistics chain, whether legally or

illegally (Karagoz, Aydin and Simic, 2022; Go et al., 2016).

ELV management includes all activities and materials related to the

interconnected financial and information flows between all ELV network

entities, including vehicle users, old vehicle collection centers, official

demolition facilities, shredder industry, recycling centers, remanufacturing,

second-hand markets, industrial landfills, and so on. This is critical for the

preservation of the environment, economic circulation, and sustainable

development in the auto industry (Simic et

al., 2021).

The ELV waste treatment process begins with the de-pollution stage,

aimed at removing harmful liquids from the ELV (for example, oil) (Sitinjak et al., 2022a; Sitinjak, et al.,

2022b). The ELV

then continues the disassembly process to dismantle the vehicle components. The

destroyed vehicle hulk is then transported to the metal crushing plant, where

the ELV’s metal and non-metallic components are posted.

Furthermore, ASR (automobile shredder residue) is the residue produced by the crushing procedure that is separated between ferrous and non-ferrous metals from the output of the crushing machine. ASR is the main non-metallic material left over from the ELV crushing process (Cossu and Lai, 2013).

There are two stages

to the research. The first phase entails a thorough review of the literature on

Indonesia’s old car policy. Following that, we carried out a literature review

to look for ELV rules in adjacent nations. In the second quantitative phase,

researchers devised a set of questions to gauge people’s attitudes toward ELV

management and their readiness to adopt it. Interviews with government

representatives in charge of automotive and environmental management in

Indonesia were used to design this questionnaire. A person over the age of 18

who lived in the JABODETABEK area was the target of the questionnaire group.

Questioners are distributed by posting Google-form links on the internet or

through the WhatsApp group.

4.1. Current Legislation

The results of a comprehensive investigation related to ELV management

in countries such as China, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and Malaysia

are shown in Table 1. Malaysia and Indonesia do not even have ELV regulations.

Although these two countries have rapid levels of automotive production,

Malaysia has an advantage over Indonesia by enforcing the age of vehicles and

already has operators that manage ELVs well.

Because of the rapid growth of the automotive in China resulted in the

country becoming the largest vehicle market in the world. In 2019, vehicle

sales in China reached 25.8 million units, the highest sales figure in the

world, followed by the US at 17.5 million units (Zhang

et al., 2022). The pace of growth in the auto industry in China

prompted the Chinese parliament to legislate the ELV in 2001, a year after the

European Union introduced legislation on the ELV (Ashari et al., 2018; Xiang & Ming, 2011). The main feature that becomes the weight

point of ELV in China is an ELV classification based on the accumulated mileage

and duration of service.

Table 1 Comparison

of ELV management between countries.

|

China |

South Korea |

Japan |

Singapore |

Taiwan |

Malaysia |

Indonesia | |

|

Government Involvement / Act: |

Statute 307 Law |

The Act for Resource Recycling of Electrical/Electronic Products and

Automobiles |

ELV Recycling Law |

Vehicle Quota System |

Waste Disposal Act |

No Law |

No Law |

|

ELV age: |

10 years or 500,000km |

Not Specified |

Min 3 years, inspection once in 2 years |

10 + 5 or 10 years |

10 years |

10 years |

Not Specified |

|

Recycling Fees paid by: |

Market-Driven (Collector pay last owner) |

Market-Driven (Collector pay last owner) |

First owner, upon purchase |

Market-Driven (Collector pay last owner) |

Manufacturer & Importer pay when purchased |

Market-Driven (Collector pay last owner) |

- |

|

Operator Size: |

367 Recycling operators, 1 pilot recycling center |

226 Recycling operators, 7 shredding & Sorting plants |

5000 Recycling operators, 140 shredding & Sorting plants |

- |

303 Recycling operators, 5 shredding & Sorting plants |

209 Recycling Operators, 0 Shredding & |

- |

|

Effectiveness: (Recovery rate) |

90% |

85% |

85% |

- |

95% |

None |

None |

ELV is receiving special attention from the Taiwanese government as a

result of an increase in the number of vehicles on the road, which has resulted

in substantial pollution and other environmental issues because of poor ELV

management techniques (Chen, Huang, and Lian, 2010). ELV is

classified as hazardous waste, including lubricants, liquid acids, and

refrigerants, which can contaminate the environment if incorrectly disposed of (Cheng et al., 2012). The Taiwanese

government founded the Recycling Fund Management Board (RFMB) in 1998,

resulting in a major increase in recycling activities throughout the country (Chen, Huang, and Lian, 2010).

Japan is home to one of the world’s most thriving automotive industries.

In 2019, Japan’s total car ownership reached 62.03 million units (JAMA, 2019). Because of the increasing rate of

car ownership in Japan, vehicle waste disposal has become a serious concern.

The government passed legislation on ELV recycling in 2002 (Simic and

Dimitrijevic, 2013). Vehicle makers and importers are required to collect

and recover chlorofluorocarbons/hydrofluorocarbons (CFC/HFCs), airbags, and

automobile crushing residues (ASR) present in ELV waste under this legislation,

which went into effect in 2005. The number of illicit ELVs in Japan has

decreased because of this rule. Japan enforces this legislation to guarantee

public safety and environmental sustainability (Zhao

and Chen, 2011).

Singapore established a vehicle quota plan because a high tax program

alone did not limit the number of automobiles on the road (Chu,

2018). Now all people in Singapore must hold a

Certificate of Entitlement (COE) to purchase a vehicle. As stated in the table,

COE is separated into five vehicle categories based on engine capacity and

power output. The Land Transport Authority (LTA) will declare the availability

of COE quotas for each category, after which the vehicles must be registered

for ten years. Even if the car has been sold within the last ten years, the

owner must comply with this requirement. After ten years, the owner may cancel

the registration and continue the certificate by paying the premium quota (Huang,

Li and Ross, 2018).

Until now, Indonesia still does not have a law related to ELV.

Previously the government has tried to impose periodic emissions test policies,

but this policy still cannot reduce the level of vehicles on the road. In

addition, emissions test policies also get much rejection from the public. Now,

ELV vehicles in Indonesia are still managed poorly by some workshops and some

scrap iron collector companies. These workshops are privately managed, and the

demolition activities do not follow the correct standards.

4.2. Questionnaire

analysis

At the beginning of the questionnaire, we analyzed the respondents’ backgrounds. Of the 98 respondents, 71 were male, and 27 were female (see Table 2). They represent several employment sectors, such as civil servants, permanent and contracted private employees, and the self-employed. In education, the highest percentage showed that most respondents were respondents from postgraduate education (61.20%). 66.7% of respondents own at least 1 or 2 private vehicles (see Figure 1).

Table 2 Result of the respondent’s background.

|

Respondent Background |

Total |

Percent |

|

Gender | ||

|

Male |

71 |

72.45% |

|

Female |

27 |

27.55% |

|

Working sector | ||

|

Civil Servant |

48 |

48.98% |

|

Permanent private employee |

29 |

29.59% |

|

Contract private employee |

8 |

8.16% |

|

Entrepreneur |

13 |

13.27% |

|

Educational Level | ||

|

Senior High School |

10 |

8.10% |

|

Bachelor |

28 |

28.60% |

|

Postgraduate |

60 |

61.20% |

Figure 1 Ownership of vehicles

This finding shows that most respondents have more than one vehicle.

People feel more comfortable and flexible working using private vehicles than

public transportation. The lack of facilities for public transportation also

causes people to avoid public transportation in Indonesia.

The second question is about social support related to ELV management.

As illustrated in Table 3, 52 people, or 53.06% of respondents gave, strongly

disagreed. This shows a lack of public support for the ELV rules. Wang et al. (2021) in their research stated

that social support is a major factor in the success of ELV management in one

country. This finding shows that the support from the community of vehicle

owners in Indonesia is still weak, so the implementation of ELV regulations is

not yet possible.

Table 3 Result

of the respondent’s answers about ELV.

|

Questions

about ELV |

The number of respondents | ||

|

Strongly disagree |

Not sure |

Strongly agree | |

|

Support

for ELV policy |

52 |

22 |

24 |

|

Knowledge

of ELV policy |

53 |

10 |

35 |

|

Mandatory

inspection |

15 |

24 |

59 |

|

Institutional

trust |

49 |

19 |

31 |

|

Implementation

of ELV |

51 |

19 |

28 |

Respondents were then asked if they were aware of the benefits of

implementing the ELV policy. As seen in Table 3, most answers are on the

public’s ignorance regarding the benefits of implementing ELV policies. This

shows that public knowledge related to the benefits of ELV management is still

very low (54.08%). Referring to Lee and Ko’s research (2021) statees

that public knowledge related to the benefits of regulation will make it easier

for people to accept the rule. These findings also corroborate that the

importance of socialization related to ELV programs is given before

implementing ELV-related laws.

The next question relates to the mandatory inspection of vehicles.

Vehicle owners are required to conduct a vehicle feasibility test every time

they want to renew their vehicle letter. As seen in Table 3, most respondents

agreed (60.20%) with the importance of conducting a vehicle feasibility check.

This is because the older the vehicle, the vehicle has the high risk of

accidents due to the lack of safety and quality owned by vehicles older than 15

years (Santini et al.,

2011).

Then all respondents were surveyed related to trust in the government.

Table 3 shows that half of the respondents (50%) do not trust the government

in the credibility of making a policy. The results of this answer tell us the

importance of governments in increasing public confidence in their performance.

The findings of Zannakis et al., Eiser et al., and Jagers et

al. (Jagers, Matti and Nilsson, 2017; Zannakis, Wallin and Johansson, 2015; Eiser, Miles and Frewer, 2002) show that public

trust in the government is the main factor that determines the community to

obey the policies made by the government.

The last question is to find out whether the ELV law is implemented in

Indonesia. Table 3 shows that most respondents (52.04%) still rejected the

implementation of ELV policies, and some respondents (19.38%) were still

undecided about ELV policies. This can be caused by several factors. First, the

number of vehicles owned by respondents can influence this decision. The

respondents think that they will spend more funds to buy a new and more

expensive vehicle.

A set of questions in this study has been prepared to find out exactly

what the public’s interest in ELV policies is if implemented in Indonesia. The dimensions

of social acceptance can be measured through attitudes, knowledge, trust in the

government, and the desire to imply it. From the results obtained in this

study, it can be seen that all respondents still gave a negative response

regarding the ELV policy.

The low public knowledge regarding ELV policies is a big homework for

the Indonesian government to provide comprehensive knowledge related to ELV

policies. From the results of the survey, it was also found that the level of

public trust in the government is very low. This strengthens that the rejection

of ELV policies can be based on the lack of public trust in the government’s

ability to make a policy. The respondents also reject the regular vehicle

inspection. This is due to the lack of public awareness to maintain the

performance of their vehicles.

In addition, the government should take an important role and take swift

action on the ELV issue. Responsible parties should conduct more research and

develop regulations and laws on ELVs similar to countries that have

successfully reduced and addressed the ELV problem. The government, the

automotive industry, and the public must work together to achieve the ELV goal.

Based the main purpose of this study is to compare ELV policies. It can be seen that other countries always take the same steps against countries that first successfully implement ELV regulations in solving ELV problems in their countries. Compared to Indonesia, so far, Indonesia still plans to conduct annual vehicle emissions checks, and no specific regulations have been made to address the ELV problem in Indonesia. When compared to Malaysia. Indonesia is still very far behind. Malaysia has moved with ELV processing plants spread across several cities, and the government has implemented vehicle age policy rules to combat the effects caused by ELV.

The findings of this study can be used to show that ELV restrictions

cannot be applied unilaterally. This is reflected in the research findings,

which show that respondents are still hesitant to use ELV management, and poor

levels of trust in the government became extensive homework. As a result, an

in-depth study is required, including the costs associated with implementing

the ELV and its financing scheme. This is because ELV integration

affects all Indonesian communities.

This

research was sponsored by the ministry of higher education, Malaysia, and the

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, via the transdisciplinary research grant scheme

project (TRGS/1/2020/UKM/02/1/2). The main contributors are CS, RF, and LS. All

authors acknowledged the content of this manuscript, and the authors declare no

conflict of interest.

Ahuja, V., Khanna, S.N., 2019. End-of-Life Vehicles

in India-Regulatory Perspectives. SAE Technical Papers, p.

2019-28-2580. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.4271/2019-28-2580

Ashari, H., Yusoff, Y.M., Zamani, S.N.M., Talib, A.N.A., 2018.

A Study of the Effect of Market Orientation on Malaysian Automotive

Industry Supply Chain Performance. International Journal of Technology,

Volume 9(8), 1651–1657

Chen, K-C., Huang, S-H, Lian, I-W., 2010. The Development

and Prospects of the End-Of-Life Vehicle Recycling System in Taiwan. Waste

Management, Volume 30(8–9), pp. 1661–1669

Cheng, Y.W., Cheng, J.H., Wu, C.L., Lin, C.H., 2012.

Operational Characteristics and Performance Evaluation of

the ELV Recycling Industry in Taiwan. Resources, Conservation and Recycling,

Volume 65, pp. 29–35

Chu, S., 2018. Singapore’s Vehicle Quota

System and its Impact on Motorcycles. Transportation, Volume 45(5), pp. 1419–1432

Cossu, R., Lai, T., 2013. Washing Treatment

of Automotive Shredder Residue (ASR). Waste

Management, Volume 33(8), pp. 1770–1775

D’Adamo, I., Gastaldi, M., Rosa, P., 2020. Recycling

of End-Of-Life Vehicles: Assessing Trends and Performances in

Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume 152, p.

119887

Dabic-Miletic, S., Simic, V., Karagoz, S., 2021. End-of-Life Tire

Management: A Critical Review. Environmental Science and

Pollution Research, Volume 28(48), pp.

68053–68070

Directorate General Of Marine Transportation (DEPHUB), 2009. Law of the

Republic of Indonesia Number 22 of 2009 Concerning Road Traffic and

Transportation. Indonesia

Eiser, J.R., Miles, S., Frewer, L.J., 2002. Trust,

Perceived Risk, and Attitudes Toward Food Technologies. Journal

of Applied Social Psychology, Volume 32(11), pp. 2423–2433

Go, T.F., Wahab, D.A., Fadzil, Z.M., Azhari, C.H.,Umeda,

Y., 2016. Socio-Technical Perspective on End-of-life Vehicle

Recovery for a Sustainable Environment. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 7(5), pp. 889–897

Harun, Z., Mustafa, W.M.S.W., Wahab, D.A.., Mansor, M.R.A.,

Saibani, N., Ismail, R., Ali, H.M., Hashim, N.A., Paisal, S.M.M., 2021. An

Analysis of End-of-Life Vehicle Policy Implementation in Malaysia from the

Perspectives of Laws and Public Perception. Jurnal Kejuruteraan, Volume 33(3), pp. 709–718

Huang, N., Li, J., Ross, A., 2018. The Impact of

the Cost of Car Ownership on the House Price Gradient in

Singapore. Regional Science and Urban Economics, Volume 68, pp. 160–171

Jagers, S.C., Matti, S., Nilsson, A., 2017. How Exposure to Policy

Tools Transforms the Mechanisms Behind Public Acceptability and Acceptance—The

Case of the Gothenburg Congestion Tax. International

Journal of Sustainable Transportation, Volume 11(2), pp.

109–119

Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association (JAMA), 2019. The Motor

Industry of Japan. Available

online at: https://www.jama.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/motor-industry-of-japan-2019.pdf,

Accessed Marc 12, 2022

Jawi, Z.M., Isa, M.H.M., Solah, MS., Ariffin, A.H.,

Shabadin, A., Osman, M.R., 2016. The future of End-Of-Life Vehicles (elv) in

Malaysia - A Feasibility Study Among Car Users in Klang Valley. In: The 2nd

International Conference on Automotive Innovation and Green Vehicle (AiGEV

2016)

Karagoz, S., Aydin, N., Simic, V., 2020. End-of-Life Vehicle

Management: A Comprehensive Review. Journal

of Material Cycles and Waste Management, Volume 22(2), pp.

416–442

Karagoz, S., Aydin, N., Simic, V., 2022. A Novel

Stochastic Optimization Model for Reverse Logistics Network Design of

End-of-Life Vehicles: A Case Study of Istanbul. Environmental

Modeling and Assessment, Volume 27(4), pp.

599–619

Kassim, K.A.A., Husain, N.A., Ahmad, Y., Jawi, Z.M., 2020.

End-of-Life Vehicles (ELVs) in Malaysia: Time for Action to Guarantee Vehicle

Safety. Journal of the Society of Automotive Engineers Malaysi, Volume 4(3), pp.

338–348

Lee, T., Ko, M.C., 2021. The Effects

of Citizen Knowledge on the Effectiveness of Government Communications on Nuclear Energy

Policy in South Korea. Information, Volume 12(1), p. 8

Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MENLHK), 2017. Regulation of the

Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia.

Indonesia

Mohamad-Ali, N., Ghazilla, R.A.R., Abdul-Rashid, S.H.,

Sakundarini, N., Ahmad-Yazid, A., Stephenie, L., 2018. End-of-life Vehicle Recovery

Factors: Malaysian stakeholders’ Views and Future Research

Needs. Sustainable Development, Volume 26(6), pp.

713–725

Statistics Indonesia (BPS), 2020. The

development of the number of motor vehicles. Available online at https://tinyurl.com/2s4w29se, Accessed date on 01/09/2022

Santini, A., Morselli, L., Passarini, F., Vassura, I., Di

Carlo, S., & Bonino, F. (2011). End-of-Life Vehicles management: Italian Material

and Energy Recovery Efficiency. Waste Management, Volume 31(3), pp.

489–494

Sharma, L., Pandey, S., 2020. Recovery of Resources from End-Of-Life

Passenger Cars in the Informal Sector in India. Sustainable Production and

Consumption, Volume 24, pp. 1–11

Simic, V. et al. 2021. Picture Fuzzy Extension of

the CODAS Method for Multi-Criteria Vehicle Shredding Facility

Location. Expert Systems with Applications, Volume 175, p. 114644

Simic, V., Dimitrijevic, B., 2013. Modelling of Automobile

Shredder Residue Recycling in the Japanese Legislative Context. Expert

Systems with Applications, Volume 40(18), pp.

7159–7167

Sitinjak, C., Ismail, R., Bantu, E., Fajar,

R.,Samuel, K.,. 2022a. The Understanding

of the Social Determinants Factors of Public Acceptance Towards the End of Life Vehicles. Cogent

Engineering, Volume 9(1), pp. 1–12

Sitinjak, C., Ismail, R., Tahir, Z., Fajar,

R., Simanullang, W.F., Bantu, E., Samuel, K., Rose, R.A.C., Yazid, M.R.M.,

Harun, Z., 2022b. Acceptance of ELV Management: The Role of Social

Influence, Knowledge, Attitude, Institutional Trust, and Health Issues. Sustainability, Volume 14(16), p. 10201

Tjahjono, T., Kusuma, A., Adhitya, M., Purnomo, R., Azzahra,

T., Purwanto, A.J., Mauramdha, G., 2021. Public

Perception Pricing into Vehicle Biofuel Policy in Indonesia. International

Journal of Technology, 12(6), pp. 1239–1249

Wang, J., Sun, L., Fujii, M., Li, Y.,

Huang, Y., Murakami, S., Daigo, I., Pan, W., Li, Z., 2021. Institutional, Technology, and Policies of End-of-Life Vehicle Recycling

Industry and Its Indication on the Circular Economy- Comparative Analysis

Between China and Japan. Frontiers in Sustainability, Volume 2, pp. 1–16

Xiang, W., Ming, C., 2011. Implementing Extended

Producer Responsibility: Vehicle Remanufacturing in China. Journal

of Cleaner Production, Volume 19(6–7), pp. 680–686

Yano, J., Xu, G., Liu, H., Toyoguchi, T., Iwasawa, H., Sakai,

S.I., 2019. Resource and Toxic Characterization in End-of-Life Vehicles

Through Dismantling Survey. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management,

Volume 21(6), pp. 1488–1504

Zannakis, M., Wallin, A., Johansson, L.O., 2015. Political

Trust and Perceptions of the Quality of Institutional Arrangements - How Do

They Influence the Public’s Acceptance of Environmental

Rules. Environmental Policy and Governance, Volume 25(6), pp. 424–438

Zhang, L., Lu, Q., Yuan, W., Jiang, S., Wu, H., 2022. Characterizing End-Of-Life Household Vehicles’ Generations in China: Spatial-Temporal Patterns and Resource Potentials. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 177, p. 105979

Zhao, Q., Chen, M., 2011. A Comparison of ELV Recycling System in China and Japan and China’s Strategies. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 57, pp. 15–21