A Novel Lanthanum-based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolyte Composite with Enhanced Thermochemical Stability toward Perovskite Cathode

Corresponding email: atiek.noviyanti@unpad.ac.id

Published at : 09 May 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 3 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i3.5189

Noviyanti, A.R., Malik, Y.T., Pratomo, U., Syarif, D.G., 2023. A Novel Lanthanum-based Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Electrolyte Composite with Enhanced Thermochemical Stability toward Perovskite Cathode. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(3), pp. 669-679

| Atiek Rostika Noviyanti | Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung-Sumedang KM. 21, Jatinangor 45363, Indonesia |

| Yoga Trianzar Malik | Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung-Sumedang KM. 21, Jatinangor 45363, Indonesia |

| Uji Pratomo | Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Mathematics and Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Raya Bandung-Sumedang KM. 21, Jatinangor 45363, Indonesia |

| Dani Gustaman Syarif | PRTNT-ORTN-BRIN, Jl. Taman Sari 71, Bandung 40132, Indonesia |

Lanthanum-based electrolytes for Solid Oxide

Fuel Cells (SOFCs) gain extensive attention due to their lower activation

energy and low-cost preparation to convert the energy stored in gaseous

chemicals into electricity. In this context, a La9.33Si6O26-La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.55

(LSO-LSGM) SOFC electrolyte composite with various mass ratio LSO:LSGM (w/w)

(5:0, 4:1, 3:2, 2:2, 2:3, 1:4) are successfully prepared for the first time

using different LSO precursors with various mass target of 3g (LSO-LSGMA)

and 5g (LSO-LSGMB), respectively. The result shows that the lower

mass target in the synthesis of LSO induced formation of protoenstatite and

coesite secondary phases on the composite of LSO-LSGM based on XRD, FTIR, and

XPS analysis. The SEM micrograph suggests that agglomeration occurred more in

LSO-LSGMA than in LSO-LSGMB. Generally, the composites

signified high chemical stability on La0.8Sr0.2Co0.6Fe0.4O2.55

(LSCF) cathode based on the XRD analysis. The LSO-LSGMA

composites which contained a high percentage of protoenstatite and coesite

resulted in an additional peak of MgSi2Sr, especially for the sample

with the mass ratio of 41 (LSO-LSGM41) suggesting that the chemical stability

of LSO-LSGMA on LSCF cathode is much lower than LSO-LSGMB.

LSCF cathode; LSO-LSGM; Solid oxide fuel cell; Solid state method

The Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC) is a device that can

generate electricity from gaseous chemicals (hydrogen or short-chained

hydrocarbon). It operates at high temperatures up to 1400K (Abdalla et al., 2018). Similar to the fuel cell (Mulyazmi et

al., 2019), the electrolyte in SOFC portrays an important role

in a set of operating temperatures and thermochemical stability at high

temperatures. Yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) with general formula (ZrO2)1-x

(Y2O3)x and can generate ionic conductivity

for oxide ion up to 2.00 × 10-1 S.cm-1 (1273K) for an ideal condition (Rahmawati et al., 2017; Preux, Rolle,

and Vannier,

2012). However, a lower

temperature can drop the conductivity to 1.02 × 10-3 S.cm-1

(973K) (Rajesh and Singh, 2014) due to high activation energy (Ea) varied

from 0.89 to 1.16 eV (Zarkov et al., 2015), and another study

noted the value as 1.21 eV (Rajesh and Singh, 2014). YSZ electrolyte is

also reported unavailable to sustain chemical stability with perovskite electrodes such as LSCF and LSM

cathode at 1300 K (Fan, Yan, and Yan, 2011; Minh and Takahashi, 1995).

Lanthanum

silicate oxides (LSO) electrolyte with the formula of La10-x(SiO4)6O2-d,

x=0.1-0.6 has a potential characteristic to substitute YSZ conventional

electrolyte. LSO is more stable than YSZ at high temperatures in the case with

no reactivity to perovskite cathode at 1300 K (Marrero-López, et al., 2010). Moreover, the Ea of LSO is much lower

than YSZ (up to 32 eV) (Kim et al., 2011) despite the

ionic conductivity that is required to be improved. The ionic conductivity of LSO varied from 1.58 × 10-2 to 3.16 × 10-1

S.cm-1 (1273 K) (Higuchi et al., 2010). The structure of LSO is made of an isolated

unit of SiO4 tetrahedral which creates disparate channels

parallel to the c-axis. The smaller of these channels contains lanthanum cations

and vacancies, while the larger one contains both lanthanum cations and oxide

ions which are responsible for the ionic conduction channel (Masson et al., 2017). The lanthanum ions are

coordinated with this isolated tetrahedral SiO4 which can form a

hexagonal structure with P

The composite

strategy is one of the best methods to manage this issue due to its ability to

signify a better result in lowering Ea rather than the doping method.

The composite method also can overcome a reduction issue in some SOFC

electrolytes that may lead to lowering electrical performance (Raza et al., 2020). LSO-YSZ (Noviyanti et al., 2016), LSO-CGO (Noviyanti et al., 2018), and LSGM-YSZ (Raghvendhra et al., 2014) denoted a

decrease of Ea as the addition of the composites, while the addition of Sr-doping to La site in LSO phase

increases the value of Ea two times larger, from 0.56 eV to 1.26 eV (Leon-Reina et al., 2004). LSGM

electrolyte was chosen with LSO for the composite due to the high ionic

conductivity (5.62 × 10-1 S.cm-1 at 1273 K) and a thermal

expansion coefficient (TEC) of 12.7 × 10-6

K-1 (Kharton, Marques,

and Atkinson,

2004), and lower Ea

than YSZ (0.82 eV) (Huang, and Goodenough, 2000). With this

combination of LSO-LSGM, it is expected to result in excellent performance and

high thermochemical stability on the LSCF cathode. Thermochemical stability is

quite important to enhance the electrochemical performance of SOFC cells during

high operating temperatures. The low thermochemical stability will lead to cell

degradation and the short life of SOFC energy generation. However, to obtain a

high-stable electrolyte composite on a typical perovskite SOFC cathode at high

operating temperature, any impurities from constituents of the composite should

be reduced. From all the aforementioned studies, the impurity effect was not

comprehensively studied. Thus, an attempt to design a novel composite of

LSO-LSGM and a thorough study of impurities effect in LSO-LSGM composite on

thermochemical stability of LSO-LSGM on LSCF cathode was carried out to

understand the origin of enhanced thermochemical stability of LSO-LSGM

composite.

To our knowledge, the detailed preparation of LSO-LSGM with various mass ratios of LSO and LSGM and its chemical stability test on the LSCF cathode has not been reported yet. Our study found that the different mass targets during the synthesis of LSO can implicitly induce a formation of protoenstatite and coesite phase in LSO-LSGM which can increase the formation of LaSrGaO4 in the LSO-LSGM/LSCF interface. This study aims to prepare the composites of LSO-LSGM and examines the chemical stability of LSO-LSGM on the LSCF perovskite cathode. The LSO precursor was synthesized using the hydrothermal method accorded with our previous study. In addition, the investigation of the effect of La(OH)3 impurities amount that was found in LSO synthesis on the phase formation in LSO-LSGM composites and chemical stability on the LSCF perovskite cathode was carried out.

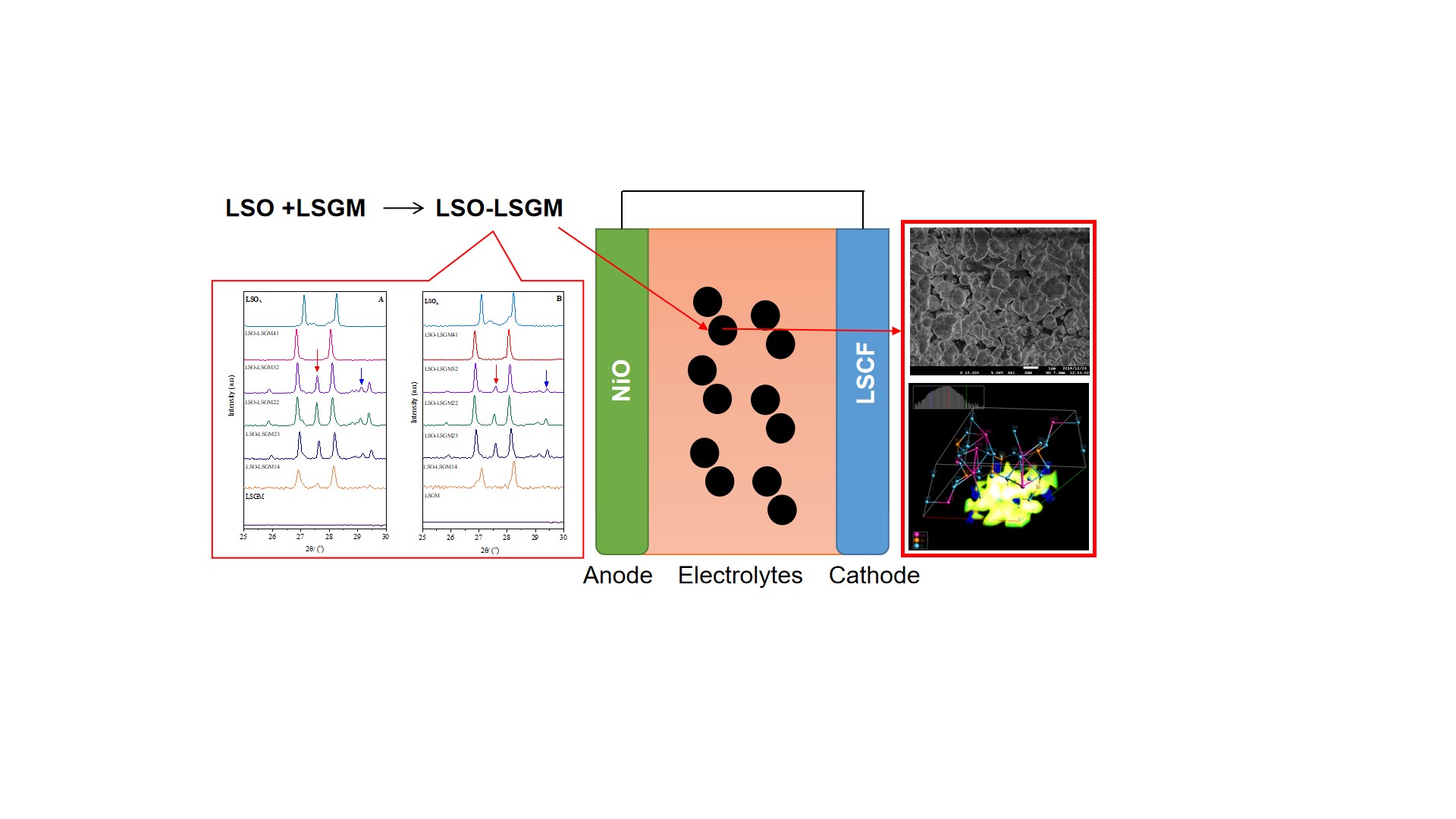

2.1. LSO-LSGM preparation

The LSO-LSGM composites were prepared

using the conventional solid-state method (Malik

et

al., 2018).

Generally, the synthesized LSO and commercially-available LSGM were mixed with

the different mass ratios in ethanol using Agate mortar. The mixture was

subsequently dried in the oven at 393K for 2h. The mixture powder was pelleted

with a circular diameter of 15 mm. The pellet of LSO-LSGM was sintered in a

furnace at 1473K for 8h as illustrated in Figure 1. LSOs with 3 and 5 g mass targets were synthesized using

the hydrothermal method as provided in our previous study (Malik et al.,

2019).

LSGM and LSCF were obtained from Sigma (99.99%, metal basis trace). The

composites were divided into two categories: A (using LSO precursors with 3 g

mass target) with various mass ratios of LSO:LSGM (w/w) = 5:0 (LSOA),

4:1 (LSO-LSGMA41), 3:2 (LSO-LSGMA32), 2:2 (LSO-LSGMA22),

2:3 (LSO-LSGMA23), 1:4 (LSO-LSGMA14), 5:0 (LSGM) and B

(using LSO precursor with 5 g mass target) with various mass ratio of LSO:LSGM

(w/w) = 5:0 (LSOB), 4:1 (LSO-LSGMB41),

3:2 (LSO-LSGMB32), 2:2 (LSO-LSGMB22), 2:3 (LSO-LSGMB23),

1:4 (LSO-LSGMB14), 5:0 (LSGM). LSO-LSGM composites were characterized using XRD (D8 Bruker Advanced) at 2range

of 10-70° with Cu K

radiation,

= 0.15418 nm and v = 0.02° min-1 to examine the crystal

structures, Fourier transformation infrared/FTIR (Fischer Scientific) to study

the chemical bonding, X-ray

photoelectron spectroscopy/XPS (JEOL JPS-9010MX) to examine the chemical state

of the composition elements, and SEM (JEOL JSM-7500f) with 10000× magnification

to analyze the microstructure of LSO-LSGM composite electrolytes.

Figure 1 Schematic

illustration of LSO-LSGM electrolyte composite preparation

2.2. Thermochemical stability analysis

Thermochemical stability was assessed

based on the level of LSO-LSGM electrolyte reactivity to the LSCF cathode.

LSO-LSGM electrolytes are mixed with LSCF cathode using ball milling for 2

hours with a mass ratio (w/w) LSO: LSGM of 1:1. This mixture is heated in a

furnace for 48 hours at a temperature of 1473 K. The heating mixture was characterized using XRD Bruker

D8 Advanced, Cu K radiation,

= 0.15418 nm, T = 298 K, v

= 0.02° min-1 in the range of 10-70°. The results of the XRD pattern

are analyzed to observe the possibility of new

crystalline phases emanating from the electrolyte-electrode interactions. The

XRD patterns were refined using Highscoreplus© (Degen et al.,

2014).

3.1. Characterization of Novel LSO-LSGM

Electrolyte Composites

The prepared LSO-LSGM composite was characterized using XRD and FTIR. The results suggested

that the formation of LSO-LSGM was successful. The detail of each

characterization is discussed below.

3.1.1. XRD Characterization

The LSO-LSGM electrolyte composites were

successfully prepared using the solid phase synthesis method. The XRD diffraction patterns varied from each

LSO-LSGM composition (as shown in Figure S1). The main peak intensity of LSGM diffraction at 2= 33° decreases

along with increasing LSO composition in LSO-LSGM composites which are

characterized by

strengthening intensities of LSO peak diffraction. Based on this XRD pattern,

the composting process ran according to our expectations, where both the LSO

and LSGM peaks are found in each LSO-LSGM diffraction composite pattern, in all

LSO-LSGM various mass ratios.

The LSGM deployed in this study has a cubic-based structure with a P m-3m

space group that correlates with La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.55

(LSGM0802) ICSD No. standard phase. 98-009-8170. The structure of

LSGM with this composition can be maintained in a mixed phase of the LSO-LSGMA32,

LSO-LSGMA22, LSO-LSGMA23, LSO-LSGMA14, and

LSO-LSGMB32, LSO-LSGMB22, LSO-LSGMB23,

LSO-LSGMB14. Meanwhile, for the LSO-LSGMA41 and LSO-LSGMB41

composite electrolytes, the LSGM constituent was compatible with the LSGM phase

of La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.55

(LSGM0901).

Figure 2 XRD pattern of LSO-LSGMA (left) and LSO-LSGMB

(right) composite electrolytes at the range of 2 = 25-30°. The coesite phase

is indicated at 2

of 27.67° and protoenstantite phase

As shown in Figure 3, the

LSO-LSGM 41 and 14 composites in both categories show a peak phase of LaGaSrO4,

which is a common secondary phase that is often found in LSGM-based

composites. This phenomenon indicates that the LaGaSrO4 phase can be

formed in composites with a low precursor composition concentration of LSGM and

LSO. Moreover, the composition of the LaGaSrO4 phase in the LSO-LSGMA

composite is known to be higher than in the LSO-LSGMB composite

which indicates that the target mass of 5g could be better than LSO with a

target mass of 3g as a precursor of LSO composites. Moreover, the formation of

coesite (SiO2) may closely relate to the preparatory stage of

LSO-LSGM electrolyte composite using the solid-phase method at 1273K (Mart et al., 2008). Meanwhile, the

presence of hydroxide (?OH) species from La(OH)3 impurities in the

LSO precursors contribute to the formation of the protoenstatite (MgSiO3)

phase in LSO-LSGM. This behavior is in line with research by Karakchiev et al. (2009), which explains that a protoenstatite phase can

be formed if species such as Mg2+, OH-, and SiO2

are introduced in the system.

The percentage of impurity phases in the LSO-LSGM electrolyte composite is shown in Table 1. The level of impurities in LSO-LSGMB was much less than that of LSO-LSGMA electrolytes. This behavior indicates that the impurity of La(OH)3 from LSO is assumed to influence the formation of the two phases. Composites prepared from LSO with lower levels of impurities tend to reduce the level of impurities on the composite electrolytes. Thus, the LSO-LSGMB composite electrolyte can be said to have better characteristics compared to the LSO-LSGMA.

Figure 3 XRD pattern of LSO-LSGMA (left) and LSO-LSGMB

(right) composite electrolytes at the range of 2 = 30-33°. LaGaSrO4

phase is indicated at 2? of ~31.5 in LSO-LSGM41 and LSO-LSGM14, respectively.

Table 1 Percentage

of impurity phase in LSO-LSGMA32, LSO-LSGMA22, and

LSO-LSGMA23 electrolyte composites.

|

LSO-LSGMA |

Coesite/ % |

Protoenstatite/ % |

|

LSO-LSGMB |

Coesite/ % |

Protoenstatite/ % |

|

32 |

16.8 |

17.5 |

|

32 |

8.3 |

9.8 |

|

22 |

14.2 |

16.8 |

|

22 |

7.6 |

12.5 |

|

23 |

6.5 |

13.5 |

|

23 |

5.4 |

11.3 |

The composite electrolyte lattice parameter of

LSO-LSGM is shown in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the LSO phase of the

LSO-LSGM composite has a larger volume of crystal cell units than the standard

LSO (589.26 Å3). Meanwhile, the LSGM phase tends to have a fixed

volume with the standard LSGM (60.01 Å3) except for LSO-LSGMA41.

This result confirmed that the LSO-LSGMA41 correlated to LSGM0901

more than to LSGM0802. The presence of La(OH)3

impurities from high LSO precursors in this composition is thought to affect

the volume expansion behavior of the cell unit of the composite electrolyte.

Another behavior that can be observed from the changes in the volume of

LSO-LSGM electrolyte composite cell units is that it induced an increase in

LSGM cell unit volume which consistently occurred in LSO-LSGM32, LSO-LSGM22,

LSO-LSGM23 (both composite categories) accordingly with the decrease in LSO

cell unit volume (Figure S2). This behavior is closely related to the discovery

of the same type of impurity phase.

Table 2 LSO-LSGMA and LSO-LSGMB

composite electrolyte lattice parameters

|

Category A (LSO-LSGMA) | ||||||||

|

Lattice Parameters | ||||||||

|

|

|

LSOA |

|

|

LSGM | |||

|

LSO-LSGM |

a=b/ Å |

c/ Å |

V/ Å3 |

a=b=c / Å |

V/ Å3 | |||

|

41 |

9.7494(8) |

7.2531(8) |

597.08 |

3.9829(9) |

63.19 | |||

|

32 |

9.7434(6) |

7.2555(0) |

596.53 |

3.9151(9) |

60.01 | |||

|

22 |

9.7372(0) |

7.2527(2) |

595.54 |

3.9154(9) |

60.03 | |||

|

23 |

9.7380(7) |

7.2537(0) |

595.72 |

3.9158(3) |

60.04 | |||

|

14 |

9.6983(4) |

7.1922(4) |

585.87 |

3.9131(8) |

59.92 | |||

|

Category B (LSO-LSGMB) | |||||||||

|

|

|

Lattice Parameters |

| ||||||

|

|

|

LSOB |

|

|

LSGM | ||||

|

LSO-LSGM |

a=b/ Å |

c/ Å |

V/ Å3 |

a/ Å |

V/ Å3 | ||||

|

41 |

9.7465(3) |

7.2517(3) |

596.60 |

3.9171(7) |

60.11 | ||||

|

32 |

9.7435(8) |

7.2552(3) |

596.52 |

3.9131(1) |

59.92 | ||||

|

22 |

9.7400(5) |

7.2538(5) |

595.98 |

3.9139(7) |

59.96 | ||||

|

23 |

9.7365(1) |

7.2536(9) |

595.53 |

3.9148(4) |

60.00 | ||||

|

14 |

9.7198(2) |

7.2411(0) |

592.46 |

3.9133(0) |

59.93 | ||||

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

To confirm the occurrence of the impurity phases of protoenstantite and

coesite and to investigate the bond interaction in the LSO-LSGM composite, FTIR

analysis was also carried out (see Figure 4). The occurrence of these

impurities may affect the chemical stability of LSO-LSGM with the LSCF cathode.

LSO has the main band at a wave number of 915?980 cm-1 which shows

the SiO4 asymmetric stretch vibration, while LSGM shows the stretch

of Ga-O bonds band at 635 cm-1, La-Mg bonds at

1470 cm-1, and Mg-O bonds at 3368 cm-1 (Byszewski et al., 2006; Baran, 1975). The increasing LSGM mass in the LSO-LSGM

composite affected band changes at 635cm-1 which corresponds to the

number of Ga-O bonds. The vibration band for the -OH bond (3600 cm-1)

that was found in LSO, does not appear at the LSO-LSGM composite. On the other

hand, there is an occurrence of the band from the Mg-O bond shown at 3368 cm-1.

The LSO-LSGMA showed a different peak from LSO-LSGMB at

2800 cm-1, which corresponds to the stretch vibration of Mg-Si of

protoenstatite phases. The Si-O-Si bonds from LSOA considerably have

contributed to an increasing intensity of wave number 1500 cm-1 due

to Mg?Si bonds in the MgSiO3 enstatite phase can occur at

1509 cm-1 (Kalinkina et al., 2001).

3.2. Fourier Map Analysis of LSO-LSGM

The Fourier map analysis was carried out to observe changes in electron

density in the ionic conduction pathway. The result of the Fourier map is shown

in Figure S3 and Figure S4. The green

color represents the high electron density level (positive) in the LSO phase

which becomes more concentrated as the level of LSGM increases. Meanwhile, the

color blue or red represents negative density or low electron density (Masson et al., 2017; Galindo-hernández, and Gómez, 2009).

The different levels

of electron density reinforce the notion that variations in target mass

synthesis can affect the fundamental characteristics of the LSO-LSGM

electrolyte composites. Composite electrolytes containing LSO with higher

impurity levels have lower electron density compared to composite electrolytes

prepared from LSO precursors with lower impurity levels.

3.3. Surface

characterization of LSO-LSGM by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Figure 5 SEM micrographs of LSO-LSGMA and LSO-LSGMB (10.000×

magnification)

3.4. X-ray

photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of LSO-LSGM

X-Ray

photoelectron spectroscopy was employed to examine the chemical state of the

composition elements and the surface properties of LSO-LSGMA and

LSO-LSGMB. The XPS spectrum is shown in Figure S5. The C1s spectrum displays a

characteristic shoulder due to carbonates at a binding energy (BE) of 289.5 eV.

The strong peak at BE 285.0 eV indicates the presence of amorphous carbon on

the surface. The BE peaks of La

3d, Sr 3d, Ga 2p, and O1s have been observed at 836, 135, 1117, and 530 eV, respectively, which is similar to Raghvendhra et al., (2014). However, Si 2s spectra were not observed at 152 eV for LSO-LSGMA. It may be due to

an overlap with the Ga 3s spectrum that emerged at 153 eV (Kharlamova, 2014).

3.5. Thermochemical stability test of LSO-LSGM

Figure 6 XRD pattern of LSO-LSGMA

(A), LSO-LSGMB

(B) composite

electrolytes at the range of 2 = 27-30°, and (C) Peak ratio of protoenstantite

phase to a neighbour peak of LSO at 2

of 28°

The LSO-LSGM composite has been successfully

prepared. The XRD pattern suggested that LSO-LSGMB has higher

thermochemical stability compared to LSO-LSGMA. This higher

stability originated from the different phase impurities in the LSO precursor

which lead to the formation of protoenstantite and coesite phases in LSO-LSGM

composites. The phases of protoenstatite

and coesite appeared in the LSO-LSGM with the range of mass ratio (LSO to LSGM)

of 3:2 to 2:3. The LSO-LSGMA contained

more coesite of 6.5 to 16.8% and protoenstatite of 13.5 to 17.5% compared to the LSO-LSGMB which showed the coesite phase

of 5.4 to 8.3% and protoenstatite of 9.8 to 11.3%. It is

believed that the amount of LSO precursor affects the formation of

coesite and protoenstatite. The characteristic behavior was confirmed by the

differences in the LSO-LSGM Fourier map which indicates the denser electron

revealed in the LSO structures in the LSO-LSGMB. In

this work, no reactivity of LSO-LSGM occurred on LSCF. The LSO-LSGM

could be the promising SOFC electrolyte with excellent chemical stability

and low impurities through an adjustment of the mass ratio between LSO and

LSGM. Moreover, it can be

confirmed that the mass target could be the

characteristic parameter in the synthesis of LSO. The optimum composition of

LSO-LSGM composite electrolyte with enhanced chemical reactivity toward LSCF

cathode which was found in this study will open a new possibility for the

development of SOFC component with low thermochemical reactivity during the

high operating temperature of SOFC cell through a key parameter of a mass

target during LSO precursor synthesis.

The

authors would like to thank the Academic Leadership Grant 2023 Universitas

Padjadjaran and Directorate General for Higher Education, Ministry of Ristek

Dikti Republik Indonesia (No. 1549/UN6.3.1/PT.00.2023) for the

financial support. The authors also thank the Department of

Applied Chemistry, Tokyo Metropolitan University for allowing the author to use

the XPS instrument.

| Filename | Description |

|---|---|

| R1-CE-5189-20230408165943.pdf | --- |

Abdalla, A.M.,

Hossain, S., Azad, A.T., Petra, P.M.I., Begum, F., Eriksson, S.G., Azad, A.K.,

2018. Nanomaterials for Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: A

Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 82, pp. 353–368

Adi, W.A., Manaf, A.,

Ridwan, 2017. Absorption Characteristics of the Electromagnetic Wave and

Magnetic Properties of the La0.8Ba0.2FexMn½(1-x)Ti½(1-x)O3

(x = 0.1–0.8) Perovskite System. International Journal of Technology,

Volume 8(5), pp. 887–897

Baran, E.J.,

1975. Infrared Spectrum of LaGaO3. Z.

Naturforsch, Volume 30, pp. 136–137

Byszewski, P.,

Aleksiyko, R., Berkowski, M., Fink-finowicki, J., Diduszko, R., Gebicki, W.,

Baran, J., Antonova, K., 2006. IR

and Raman Spectroscopy Correlation with The Structure of (La/Pr)1-x(Pr/Nd)xGaO3

Solid Solution Crystals. Journal of Molecular Structure, Volume 793, pp. 62–67

Degen, T., Sadki, M., Bron, E., König,

U., Nénert, G., 2014. The HighScore Suite. Powder Diffraction, Volume

29(S2), pp. S13–S18

Fan, B., Yan,

J., Yan, X., 2011. The Ionic Conductivity, Thermal

Expansion Behavior, and Chemical Compatibility of La0.54Sr0.44Co0.2Fe0.8O3- as

SOFC Cathode Material. Solid State Sciences, Volume 13(10), pp, 1835–1839

Galindo-Hernández, F., Gómez, R., 2009.

Fourier Electron Density Maps for Nanostructured TiO2 and TiO2-CeO2 Sol-Gel

Solid. Journal of Nano Research, Volume 5,

pp. 87–94

Higuchi, Y.,

Sugawara, M., Onishi, K., Sakamoto, M., & Nakayama, S. 2010. Oxide Ionic Conductivities of Apatite-Type

Lanthanum Silicates and Germanates and Their Possibilities as an Electrolyte of

Lower Temperature Operating SOFC. Ceramics International, Volume 36(3), pp. 955–959

Huang, K.Q.,

Goodenough, J.B., 2000. A

Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Based on Sr- And Mg-Doped LaGaO3 Electrolyte:

The Role of a Rare-Earth Oxide Buffer. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. Volume 303, pp. 454–464

Kalinkina, E.V,

Kalinkin, A.M., Forsling, W., Makarov, V.N., 2001. Sorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide and structural

changes of Ca and Mg silicate minerals during grinding. International

Journal of Mineral Processing.

Volume 61(4), pp. 289–299

Karakchiev,

L.G., Avvakumov, E.G., Gusev, A.A., Vinokurova, O.B., 2009. Possibilities of Exchange Mechanochemical

Reactions in the Synthesis of Magnesium Silicates. Chemistry for Sustainable Development, Volume 17, pp. 581–586

Kharlamova,

T.S., Matveev, A.S., Ishchenko, A. V, Salanov, A.N., Koshcheev, S. V, Boronin,

A.I., Sadykov, V.A., 2014. Synthesis and Physicochemical and Catalytic

Properties of Apatite Type Lanthanum Silicates. Kinetics and

Catalysis, Volume 55(3), pp. 361–362

Kharton, V.V.,

Marques, F.M.B., Atkinson, A., 2004.

Transport Properties of Solid Oxide Electrolyte Ceramics: A Brief Review. Solid

State Ionics, Volume 174(1–4), pp.

135–149

Kim, Y., Shin,

D.-K., Shin, E.-C., Seo, H.-H., Lee, J.-S., 2011. Oxide Ion Conduction Anisotropy Deconvoluted in

Polycrystalline Apatite-Type Lanthanum Silicates. Journal of Materials

Chemistry, Volume 21, pp. 2940–2949

León-Reina, L.,

Losilla, E.R., Martínez-Lara, M., Bruque, S., Aranda, M.A., 2004. Interstitial

Oxygen Conduction in Lanthanum Oxy-Apatite Electrolytes. Journal of

Materials Chemistry, Volume 14(7), pp. 1142–1149

Malik, Y.T.,

Noviyanti, A.R., Syarif, D.G., 2018.

Lowered Sintering Temperature on Synthesis of La9.33Si6O26

(LSO) – La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.55

(LSGM) Electrolyte Composite and the Electrical Performance on La0.7Ca0.3MnO3

(LCM) Cathode. Journal of Scientific and Applied Chemistry, Volume

21(4), pp. 205–2010

Martinez, J.R.,

Vázquez-Durán, A., Martinez-Duran, G., Ortega-Zarzosa, G., Palomares-Sánchez,

S.A., Ruiz, F., 2008. Coesite Formation at Ambient

Pressure and Low Temperatures, Advances in Materials Science and

Engineering, Volume 2008,

p. 406067

Masson, O.,

Berghout, A., Béchade, E., Jouin, J., Thomas, P., Asaka, T., Fukuda, K., 2017. Local Structure and Oxide-Ion Conduction

Mechanism in Apatite-Type Lanthanum Silicates. Science and Technology of

Advanced Materials, Volume 18(1), pp. 644–653

Minh, N.Q.,

Takahashi, T., 1995. Cathode. Science and Technology

of Ceramic Fuel Cells. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V.

Mulyazmi, Daud, W.R.W., Rahman, E.D.,

Purwantika, P., Mulya, P.A., Sari, N.G., 2019. Effect of Operating Conditions

on the Liquid Water Content Flowing Out of the Cathode Side and the Stability

of PEM Fuel Cell Performance. International Journal of Technology, Volume 10(3),

pp. 634–643

Noviyanti, A.R.,

Hastiawan, I., Eddy, D.R., Adham, M.B., Hardian, A., Syarif, D.G. 2018. Preparation and Conductivity Studies of La9.33Si6O26

(LSO) -CeE0.85Gd0.15O1.925 (CGO15)

Composite Based Electrolyte for IT-SOFC. Oriental Journal of Chemistry,

Volume 34(4), pp. 2125–2130

Noviyanti, A.R.,

Irwansyah, F.S., Hidayat, S., Hardian, A., Syarif, D.G., Yuliyati, Y.B.,

Hastiawan, I., 2016. Preparation and Conductivity of

Composite Apatite La9.33Si6O26 (LSO)-Zr0.85Y0.15O1.925

(YSZ). In: AIP Conference Proceedings, Volume 1712(1), p. 050002

Noviyanti,

A.R., Juliandri, J., Winarsih,

S., Syarif D.S., Malik, Y.T., Septawendar,

R., Risdiana R., 2021. Highly Enhanced Electrical Properties of

Lanthanum-Silicate-Oxide-Based SOFC Electrolytes with Co-Doped Tin and Bismuth

in La9.33-xBixSi6-ySnyO26.

RSC Advances, Volume 11, pp. 38589–38595

Preux, N., Rolle, A., Vannier, R.N., 2012. Electrolytes and Ion Conductors Forfor Solid Oxide Fuel

Cells (SOFCs). Woodhead

Publishing Limited

Raghvendra,

Singh, R.K., Singh, P., 2014.

Electrical Conductivity of LSGM-YSZ Composite Materials Synthesized via Coprecipitation

Route. Journal of Materials Science, Volume 49(16), pp. 5571–5578

Rahmawati, F., Permadani, I., Syarif, D.,

Soepriyanto, S., 2017. Electrical Properties of Various Composition of Yttrium

Doped-Zirconia Prepared from Local Zircon Sand. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 8(5), pp. 939–946

Rajesh, R.,

Singh, K., 2014. Electrical Conductivity of LSGM –

YSZ Composite Materials Synthesized via Coprecipitation Route. Journal of Materials Science, Volume 49(16), pp. 5571–5578

Raza, R., Zhu,

B., Ra, A., Raza, M., Lund, P., 2020.

Functional Ceria-Based Nanocomposites for Advanced Low- Temperature (300-600°C) Solid Oxide Fuel Cell: A Comprehensive

Review. Materials Today Energy, Volume 15, p. 100373

Zarkov, A., Stanulis, A., Sakaliuniene, J., Butkute, S., 2015. On The Synthesis of Yttria-Stabilized

Zirconia: A Comparative Study. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology.

Volume 76(2), pp. 309–319