Classification of SMEs According to Their ICT Implementation

Corresponding email: laimac.alfonsoo@ecci.edu.co

Published at : 01 Apr 2022

Volume : IJtech

Vol 13, No 2 (2022)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i2.4981

Alfonso-Orjuela, L.C., Cancino-Gómez, Y.A., Perea- Sandoval, J.A. 2022. Classification of SMEs According to Their ICT Implementation. International Journal of Technology. Volume 13(2), pp. 229-239

| Laima Catherine Alfonso-Orjuela | Department of Marketing and advertisement, Faculty of Economics and Business Science, Universidad ECCI, Cra. 19 No. 49-20, Bogotá, Colombia, postal code 111311 |

| Yezid Alfonso Cancino-Gómez | Department of Marketing and advertisement, Faculty of Economics and Business Science, Universidad ECCI, Cra. 19 No. 49-20, Bogotá, Colombia, postal code 111311 |

| Julio Alberto Perea- Sandoval | Postgraduate School, Universidad ECCI, Cra. 19 No. 49-20, Bogotá, Colombia, postal code 111311 |

Small

and medium enterprises (SMEs) are firms that have a wide impact on the country’s

economy in Colombia and contribute 28% of GDP, so it is essential to achieve

the competitiveness of these organizations. The government has promoted plans

to adopt information and communications technologies (ICT) at SMEs to increase

their productivity and competitiveness. SMEs are organizations that lag behind

in technology adoption. Several investigations have been carried out to

characterize them, but no questions have been raised regarding the different

types of SMEs that can be found according to their ICT implementation. This

research aimed to determine the current usability and perception in the

implementation of ICT and subsequently classify organizations based on these

two factors. The results describe five types of SMEs: those that experience,

those that have been negligent, those that lag behind, those that hesitate, and

those that improvise. The data were collected in 2019, reflecting the state of

SMEs before the lockdown due to the SARS-CoV-2 virus outbreak.

ICT implementation; Small and medium-sized enterprises; SME competitiveness; SME innovation

Technology

has become fundamental support for SMEs (Hernández

et al., 2017) to support the business model, generating greater

efficiency and effectiveness of its management (Córdoba,

2015); the implementation of technological tools in SMEs is presented as

a necessity to facilitate processes like operations or production and others to

connect with consumers, generating impact and recognition, however, the needs

of sophisticate ICT technology continues (Suryanegara

et al., 2019). It is not enough to have skill and agility in management

processes to achieve competitiveness (Qosasi et

al., 2019); that is why it is necessary to develop new strategies to

improve focus in the business area (Fonseca, 2013)

understanding the concept of the digital economy as an innovative model, which

generates social and economic impact, the result of the implementation of ICT (Katz, 2015).

In spite of the fact that SMEs bring economic growth to the nation,

there are factors that hinder their development, such as the ignorance and fear

of entrepreneurs to make an investment in ICT, although the National

Competitiveness and Infrastructure Strategyproposed in 2014 granted 10% of royalties to the Science, Technology,

and Innovation Fund (FCTI), a reform that sought to encourage production and

research capacities (Private Council of Competitiveness,

n.d.) The policies regarding ICTs set out in the plan “Vive Digital

2010–2014” (Ministry of ICT, 2011) to

massify the use of technologies to guide the strategy are focused on the

productive sector and end-user to increase the levels of competitiveness in

each of the economic sectors and establish innovation as the main axis for the

development of business initiatives (Cristancho et

al., 2021).

Economic advances have been made in the countries that

have invested in science, technology, and innovation activities (STIAs),

reaching a high level in producing even more sophisticated goods and services (Novick et al., 2013). Despite the investment made

in STIAs, the results remain low compared to other regions’ countries, under 1%

of GDP. The country has been focused on the development of increasingly

demanding processes and activities, aiming to be competitive based on its

business, mainly SMEs, a reason to implement IT in various sectors such as

commercial, production, and logistics development, and allowing interconnection

according to the demands of globalization (Puentes,

2017), despite the backwardness in innovation, to increase productivity (Private Council of Competitiveness, 2018).

The

size should be relative to the performance sector (Montoya

et al., 2010) due to the relevance of SMEs because, in addition to

representing almost 100% of all firms, in countries of the Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), SMEs generate more than half of

the employment (OECD, 2002, cited by Blázquez-Santana et al., 2006). It achieves 35% of

the GDP (Ministry of Labor and Social Security of

the Government of Colombia, 2019). Nevertheless, it represents 3.86% in

2005 and 6.73% in 2019 of all enterprises (Table 1). SMEs face various

obstacles: shortage of response to their needs in aspects of knowledge, skills,

and capacity development in human capital, difficulty in accessing credit, and

reducing the purchase and investment in ICT. Also, limitations in technology

innovation advice and its applicability become barriers that hinder growth (Zevallos, 2006) and generate internal

deficiencies (Zambrano-Alcívar, 2018).

Table 1

Number of establishments according to their size at the national level

|

Company Size |

Number of

Businesses in 2005 |

Share |

Number of

Businesses in 2019 |

Share |

|

Micro business |

1,336,051 |

96.01% |

1,504,329 |

92.8% |

|

Small |

46,200 |

3.3% |

87,761 |

5.41% |

|

Medium |

7,447 |

0.53% |

21,459 |

1.32% |

|

Big company |

1,844 |

0.13% |

6,793 |

0.4% |

|

Total |

1,391,542 |

|

1,620,342 |

100% |

Note: Prepared from DANE (2005) and

Applied Economics (2019).

For SMEs, the biggest barrier is the costs that imply

ICT, as well as the financing to achieve greater technological investment and

the adaptation of technology in systems and processes that meet the needs.

Financing and adaptation represent a medium incidence and, to a lesser extent,

the availability of information and the supply of services (Rodríguez, 2003); also, the human capital gap is

a complex problem due to (1) the limited production of graduates in STEM areas

and (2) the lack of critical mass in capacities necessary to work on digital

innovation (Katz, 2015).

What digital transformation brings to businesses is

the ability to reach their customers, monitor their workforce, and reach out to

their suppliers anytime; this allows automation, standardization, and control,

management, performance, productivity per worker (Confecámaras,

2018; Shoushtary, 2013) and, enhance

the satisfaction of their customers (Berawi, et

al., 2020), but ACOPI (2017) argues

that SMEs requires greater integration into global information networks and

value chains because the impact of the digitization of production processes and

the level of productivity of the countries is not linear and depends on

variables such as quality of human capital, innovative capacity, and organizational

changes (Cimoli et al, 2009; Balboni et al, 201).

The implementation of ICTs must involve training,

given that the economy forces organizations to be changing permanently to

respond to new demands (Cardona-Mejia, 2018).

To be profitable, an organization must innovate (Freel,

2005), thereby achieving product improvement and cost reduction, profit

increase, and market share expansion (Heredia,

2010). In this way, technology generates changes both inside and outside

the organizations.

Although the accelerated technological advance

supposes business growth, SMEs are those types of organizations that present

more lag and, given their contribution to the economy, it is necessary to

inquire about the current uses and the perception of the implementation of ICT

in these SMEs and comprehend the different states in which SMEs could be

classified based on the two factors mentioned. Technological trends related to

mobile apps, security or data protection in information, cloud computing, big

data, and business intelligence are presented. These are an opportunity to

access ICT at a lower cost compared to on-site technologies (Marston, 2011). This applies to many practices,

including customer management and organizational planning (Gálvez et al., 2014).

In 2010, micro-enterprises increased their use of the

internet by 20% (Ortega, 2014); however, Weiss (2010) indicates that the perspective is

regrettable considering the different factors that influence the current era,

that technology represents daily life, and that development of systems focused

on the needs of users is becoming faster.

It shows great differences between service

SMEs in the use of ICT, which reflects that the sector is not competitive, the

government’s actions have not been effective in spreading the use of

technology, and, finally, there is scarcity of knowledge on the part of the

entrepreneur to take advantage of the available and accessible technology.

Micro-business

and SME-type firms represent a great contribution to the Colombian economy,

with more than 90% of the national productive sector, contributing 35% of GDP

and generating 80% of employment (Ministry of Labor and Social Security of the

Government of Colombia, 2019), but only SMEs contribute 28% of GDP, 67% of

employment, and 37% of national production (Hoyos-Estrada & Sastoque-Gómez,

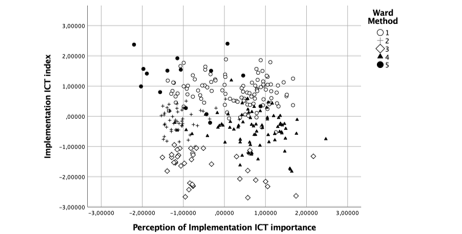

2020). The findings have allowed us to establish five groups of firms delimited

by the use of technological tools, departmentalization, and perception of how

critical it is to implement ICTs in the organization.

Cluster 1

(36.7%) has defining as the business that experiments in the use and

implementation of ICTs, tend to turn out more complex in their

departmentalization, and has more technological implementation in key areas, but

they do not show complete comprehension of the importance of implementing ICTs.

Cluster 4 (27.3%) is defined as those organizations that are negligent with the

implementation of ICTs, the firms in this class are aware of the importance of

ICTs but have not acted to a greater degree of implementation of ICTs. This

cluster 2 (17.5%) is named firms that hesitate in the use and implementation of

ICTs, due having a lower perception of how critical it is to implement ICTs in

the organization; and Cluster 3( 13.3%) has defining as the

organizations lagging behind in the use and implementation of ICTs, corresponds

to young firms, with the least degree of departmentalization and less use of

ICTs and their employees have lower rates of knowledge in ICTs, as well as

a lower frequency in the use of electronic equipment. Cluster 5 (5.2%) as firms

that improvise in the use and implementation of ICT, which has, on average

around 20 years in market. They have a greater departmentalization and use

technological tools more frequently, despite having a low perception of the

importance of implementing ICT.

To advance

future research, it is suggested to inquire about the gap between service SMEs

that implement ICT and those that do not to expose the factors that enable or

limit the acquisition and use of ICT. Moreover, the data presented

contextualize the ICT implementation prior to the start of the pandemic period,

and because it has accelerated entrepreneurship, innovation, and digitization (Gavrila & de Lucas, 2021), it is convenient to reflect the changes adopted

during the current scenario.

ACOPI (Colombian

Association of Small Industrialists), 2017. Informe de resultados

de encuesta de desempeño empresarial (Business

Performance Survey Results Report). Available online at

https://acopi.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/INFORME-DE-RESULTADOS-ENCUESTA-3er.-TRIMESTRE-DE-2017.pdf,

Accessed on Agosto 10, 2021

Applied

Economics, 2019. Cuántas empresas hay en Colombia? (How Many

Companies Are There in Colombia?). Available online at http://economiaaplicada.co/index.php/10-noticias/1493-2019-cuantas-empresas-hay-en-colombia,

Accessed on Agosto 2, 2021

Balboni,

M., Rovira, S., Vergara, S., Cepal, N., 2011. ICT in Latin America: A Microdata Analysis. United Nations,

Chile

Blázquez-Santana,

F., Dorta-Velázquez, J.A., Verona-Martel, M.C., 2006. Factors of the

Managerial Growth. Special Reference to the Small and Medium Companies. Innovar: Revista de ciencias administrativas y sociales, Volume 16(28), pp. 43–56

Berawi,

M.A., Suwartha, N., Asvial, M., Harwahyu, R., Suryanegara, M., Setiawan, E.A.,

Surjandari, I., Zagloel, T.Y.M., Maknun, I.J., 2020. Digital Innovation:

Creating Competitive Advantages. International

Journal of Technology. Volume 11(6), pp. 1076-1080

Cardona-Mejía, L.M.,

2018. Change Management in Organizations. Revista

Expomotricidad. Universidad de Antioquia. Available online at

https://revistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/expomotricidad/article/view/336101

Accessed on June 8, 2021

Confecámaras (Network of Chambers of Commerce), 2018. Determinantes de la Productividad de las Empresas de Crecimiento Acelerado. Cuadernos de análisis económico (Determinants of the Productivity of Accelerated Growth Companies. Economic Analysis Notebooks). Available online at https://www.confecamaras.org.co/phocadownload/2018/Cuadernos_An%C3%A1lisis_Econ%C3%B3mico/Cuaderno

_de_Determinantes_de_la_productividad/Cartilla%20Determinantes%20Agosto%2024-1%20OK.pdf,

Accessed on Agosto 2, 2021

Cimoli,

M., Dosi, G., Stiglitz, J.E., 2009. Industrial Policy and

Development: The Political Economy of Capabilities Accumulation. New York: Oxford

Cristancho,

G.J., Ninco, F.A., Cancino, Y.A., Alfonso, L.C., Ochoa, P.E., 2021. Key Aspects of the

Business Plan for Entrepreneurship in the Colombian Context. Suma de

Negocios, Volume 12(26), pp. 41–51

Córdoba, M.M., 2015.

Technology Implementation as a Strategy to Enhance Productivity and

Competitiveness of Clothing Manufacturing SMEs in Medellin. Trilogía. Sciencie,

technology and society, Volume 7(12), pp. 3–5

DANE (National

Administrative Department of Statistics), 2005. National Census 2005. Available

online at https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/censo-general-2005-1 , Accessed on Agosto 8, 2021

Freel, M., 2005.

Perceived Environment Uncertainty and Innovation in Small Firms. Small

Business Economics, Volume 25, pp. 49–64

Fonseca, D.E., 2013.

Development and Implementation of ICT in SMEs in Colombia - Boyaca. Revista

FIR, FAEDPYME International Review, Volume 2(4), pp. 49-59

Gálvez,

E.J., Riascos, S.C., Contreras, F., 2014. Influence of Information and Communication

Technology on the Performance of Colombian Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

Estudios Gerenciales, Volume 30(133), pp. 355–364

Gavrila, S., de

Lucas, A., 2021. COVID-19 as an Entrepreneurship, Innovation, Digitization and

Digitalization Accelerator: Spanish Internet Domains Registration Analysis. British Food Journal, Volume 123(10),

pp. 3358–3390

Heredia, L.J.U.,

2010. El cambio de los sistemas de control de gestión: Estudio de caso múltiple

en PyMEs (The Change of Management

Control Systems: Multiple Case Study in SMEs). Investigación y

Ciencia, Volume18 (47), pp. 75–82

Hernández,

R.V.R., Escandón, J.M.S., Mendoza, A.L., Izaguirre, J.A.H., 2017. Technology: A Support

Tool for SMEs (Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises) and Entrepreneurs from the

University Environment. CIENCIA Ergo-Sum, Revista Científica

Multidisciplinaria de Prospectiva, Volume 24(1), pp. 75–82

Hernández-Sampieri,

R., Torres, C.P.M., 2018. Metodología

de la investigación. Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta (Investigation

Methodology. The Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Routes). Mc Graw-Hill,

Ciudad de México

Hoyos-Estrada,

S., Sastoque-Gómez, J., 2020. Digital Marketing as a Digitalization Opportunity for

SMEs in Colombia in the Time of Covid-19. Revista Científica

Anfibios, Volume 3(1), pp. 39–46

Jones,

C., Motta, J., Alderete, M.V., 2016. Strategic Management of Information and

Communication Technologies and Electronic Commerce Adoption in MSME from

Córdoba, Argentine. Estudios Gerenciales, Volume

32(138), pp. 4–13

Katz, R.,

2015. El ecosistema y la economía

digital en América Latina (The Ecosystem and the Digital Economy in

Latin America). Fundación Telefónica, Editorial Ariel. S.A., España

Law 905, 2004. Por medio de la cual se modifica la Ley 590 de 2000 sobre

promoción del desarrollo de la micro, pequeña y mediana empresa colombiana y se

dictan otras disposiciones (By Means of

Which Law 590 of 2000 on Promoting the Development of Colombian Micro, Small

and Medium Enterprises Is Modified and Other Provisions Are Issued). Imprenta

Nacional de Colombia, Diario Oficial. Available online at http://svrpubindc.imprenta.gov.co/diario/index.xhtml Accessed on Agosto 12, 2021

López-Roldán,

P., Fachelli, S., 2015. Metodología

de la investigación social cuantitativa (Methodology

of Quantitative Social Research). Universitat de Barcelona,

España

Marston, S.L., 2011.

Cloud Computing—The Business Perspective. Journal Decision Support Systems

Archive, Volume 51(1), pp. 176–189

Marulanda,

C.E., López, M., 2013. Knowledge Management in Colombian SMEs. Revista Virtual

Universidad Católica del Norte, Volume 1(38), pp. 158–170

Méndez,

J.A.C., Paez, J.A.P., Marino, S.Q., Cádiz, M.M.M., Vazquez, R.R., Rozo, J.J.P.,

2017. Communication & ICT Perception of Students and Teachers of the Use

of Technological Platforms in Learning by Competencies. Luciernaga,

Volume 9(17), pp. 80–86

Ministry of ICT.,

2011. Vive digital Colombia. Versión 1.0 https://www.mintic.gov.co/images/MS_VIVE_DIGITAL/archivos/Vivo_Vive_Digital.pdf

Accessed on Agosto 12, 2021

Ministry of Labor and

Social Security of the Government of Colombia, 2019. MiPymes representan más

del 90 del sector productivo y genera el 80% del empleo en Colombia (MSMEs Represent More Than 90 of the

Productive Sector and Generate 80% of Employment in Colombia). Minister

Alicia Arango. Available online at https://www.mintrabajo.gov.co/prensa/comunicados/2019/septiembre/mipymes-representan-mas-de-90-del-sector-productivo-nacional-y-generan-el-80-del-empleo-en-colombia-ministra-alicia-arango

Accessed on Agosto 10, 2021

Montoya,

R.A., Montoya, R.I., Castellanos, O., 2010. Current Competitiveness of Colombian SMEs:

Determining Factors and Future Challenges. Agronomía Colombiana, Volume

28(1), pp. 107–117

Novick, M., Rotondo,

S., 2013. El desafío de las TIC en

Argentina: Crear capacidades para la generación de empleo (The Impact

of ICTs on Labor Productivity: Some Indications for SMEs in the Argentine

Manufacturing Sector. The ICT Challenge in Argentina: Creating Skills for Job

Creation). Naciones Unidas, CEPAL, Santiago de Chile, Chile

Ortega,

C.A., 2014. Incorporation of ICT into Colombian Businesses. Suma de Negocios,

Volume 5(10), pp. 29–33

Private Council of

Competitiveness, n.d. National Competitivities Report 2017-2018. Bogotá,

Colombia. Available online at https://compite.com.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CPC_INC_2017-2018-web.pdf

Accessed on Agosto 10, 2021

Private Council of

Competitiveness, 2018. Anuario Mundial de Competitividad IMD 2018 Boletín

Consejo Privado de Competitividad (World Competitiveness Yearbook IMD 2018

Private Council on Competitiveness Bulletin). Available online at https://compite.com.co/anuario-mundial-de-competitividad-imd-2018/

Accessed on Agosto 10, 2021

Qosasi,

A., Maulina, E., Purnomo, M., Muftiadi, A., Permana, E., Febrian, F. (2019). The Impact of

Information and Communication Technology Capability on the Competitive

Advantage of Small Businesses. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 10(1), pp. 167–177

Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE), 2002. OECD Small and Medium

Enterprise, Outlook. Available online at

http://www.oecd.org/ Accessed on Agosto 10, 2021

Puentes, R., 2017.

Analysis of the Adoption and Use of ICT by Colombian SMEs. IUSTA, Volume

1(46), pp. 19–41

Rodríguez,

A.G., 2003. La Realidad de la Pyme

Colombiana, Desafío para el desarrollo (The Reality of the

Colombian SME, Challenge for Development). Fundes, Colombia

Shoushtary, M.A. 2013.

Effect of Information Communication Technology on Human Resources Productivity

of the Iranian National Oil Company. International

journal of technology, Volume 4(1), pp. 56–62

Suryanegara, M.,

Harwahyu, R., Asvial, M., Setiawan, E.A., Kusrini, E. 2019. Information and

Communications Technology (ICT) as the Engine of Innovation in the Co-evolution

Mechanism. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 10(7), pp. 1260–1265

Weiss,

A., 2010. Use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in Colombian

companies. IB Magazine of the Andean Center for Higher Studies CANDANE, Volume 4(1), p. 7

Zambrano-Alcívar,

K.G., 2018. SMEs and Their Business Problems. Revista Científica

FIPCAEC (Fomento de la investigación y publicación en Ciencias Administrativas,

Económicas y Contables). Polo de Capacitación, Investigación y Publicación

(POCAIP), Volume 3(8), pp. 3–24

Zevallos, E., 2006. Obstáculos en el desarrollo de las pequeñas y

medianas empresas en Latinoamérica (Obstacles in the Development of Small and

Medium-Sized Companies in Latin America). Journal of Economics, Finance and

Administrative Science, Volume 11(20), pp. 75–96