The Effects of Using Electronic Maps While Driving on The Driver Performance

Published at : 28 Jul 2023

Volume : IJtech

Vol 14, No 5 (2023)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v14i5.4778

Lady, L., Umyati, A. 2023. The Effects of Using Electronic Maps While Driving on The Driver Performance. International Journal of Technology. Volume 14(5), pp. 1029-1038

| Lovely Lady | Industrial Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, University of Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa. Jln. Jend. Sudirman km 3, Cilegon – 42435, Indonesia |

| Ani Umyati | Industrial Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, University of Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa. Jln. Jend. Sudirman km 3, Cilegon – 42435, Indonesia |

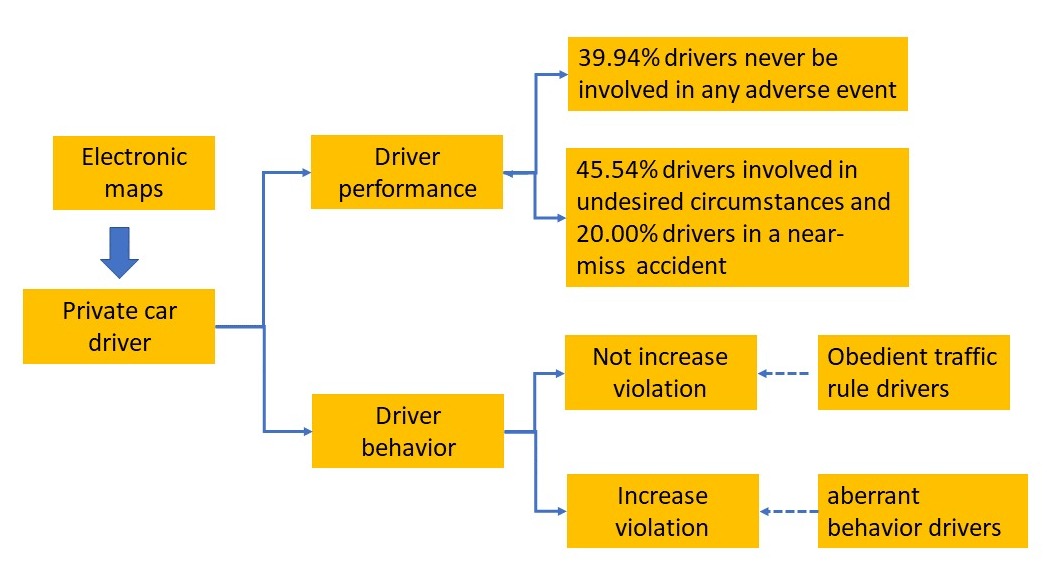

The development of information technology has

provided electronic maps (e-maps) via mobile phones that help drivers find the

travel destinations, but using mobile phone also can disturb the driver’s concentration. The aims of the research

is to analyze the effects of using e-maps while driving on driver performance. The respondents

were private car drivers, and as many as 325 respondents filled out the

questionnaire. The drivers answered the

questions about their experience using e-map while driving and particular

behavior. As many as 45.54% of drivers involved in undesired circumstances such as changing lanes or

slowing down suddenly and 20.00% involved in a near-miss

accident. Meanwhile 39.94% of drivers stated to never be involved in any adverse event. The group of drivers who have

aberrant behavior was involved in adverse event more often than the group of

drivers who obey the rules (t-test, a=0.000).

Regression analysis is performed to analyze the correlation between four types

of aberrant behavior and the driver violations, there were moderate

correlations between the research variables. The use of e-maps do not increase traffic violations when

applied by obedient traffic rule drivers, but it does increase when

applied aberrant behavior drivers.

Aberrant behavior; Driver behavior; Error; Electronic map; Violation

Using electronic maps (e-maps) via mobile phones helps drivers find

travel destinations. These applications often used by drivers for guidance

while driving. Using e-maps while driving is a secondary task; all activities

that is done while driving not related to controlling or maneuvering the

vehicle and monitoring the traffic are considered as secondary tasks in

driving. Secondary tasks can disturb the driver’s concentration and cause

longer driver reaction times (Kaber et al., 2012). Driving a vehicle is a complex task that requires not only physical

skills for controlling the direction and speed of a vehicle, but also mental

skills for sustained monitoring of integrated perceptual and cognitive inputs

that allow a driver to make time-appropriate decisions. The use of mobile

phones while driving interferes concentration and it can cause the driver

experience a near miss or even an accident.

Drivers’ impaired concentration while driving is caused by external factors unrelated to driving activities. Concentration disorders affect drivers’ abilities to make decisions and decrease their performance while driving (Zuraida, Wijayanto, and Iridiastadi, 2022; Prat et al., 2017; Zuraida Iridiastadi, and Sutalaksana, 2017; Misokefalou et al., 2016; Eliou and Misokefalou, 2014; Kaber et al., 2012; Owens, McLaughlin, and Sudweeks, 2011). Included in this task are talking to passengers, smoking, listening to music, and using a mobile phone. The secondary tasks that require visual attention and psychomotor coordination significantly decrease driving performance, but the secondary tasks that only require memory scanning and the use of auditory modality, such as listening to music or the radio, do not decrease driving performance (Rodrick, Bhise, and Jothi, 2013).

Distraction is the process of breaking down the attention to driving

activities, which reduces the awareness, readiness, and performance of drivers,

making the driver’s reaction takes longer time when an event occurs. When

distracted, the driver’s attention moves from the traffic to objects that

interest them such as objects, advertising, or other things. Distraction

increases errors in driving and leads to accidents (Young and

Salmon, 2012). Distraction can cause cognitive failures that leads to errors on simple

tasks that should be easily accomplished. Cognitive abilities can vary between

people depends on their habits and skill mastery. Cognitive failure scores are

strongly correlated with the error rate in driving, but it is not correlate

with accidents experienced by drivers. In a study by Allahyari et al. (2008) stepwise regression analysis was performed for scoring factors that have

strong correlations with driving errors, and only the factors of lack of

concentration and social interaction had strong correlations with driving error

rates (Allahyari et

al., 2008). Distraction in the form of spatial reasoning tasks, such as the driver’s

secondary tasks, decrease the driver’s performance of the primary task of

driving: in research by (Hurts, 2011) demonstrated the spatial

reasoning version of the secondary task forced the participants to think about

the east–west orientation of familiar cities, data of reduced scores of driving

skills were measured with the Lane-Change Task.

Smartphone use makes drivers divide their attention. Smartphones allow

drivers to access information unrelated to driving activities, such as

entertainment or social media. Included in entertainment activities are

listening to or watching content related to music, the radio, and information.

Research about mobile phone use while driving has been conducted by several

researchers. Mobile phone use decreases driver performance, reaction time, and

awareness (Prat et al.,

2017; Oviedo-Trespalacios

et al., 2017). According to research by (Van-Dam, Kass,

and VanWormer, 2020), audible text messages decrease the driver’s awareness and increase the

speed of the vehicle for 10 seconds after the driver gets a message

notification. Mcnabb and Gray

(2016) stated that there a decrease in driver performance when using mobile phones

as assessed from brake reaction times, which significantly greater for drivers

who use smartphones to read information or text-based conditions than for those

who use smartphones to obtain

information by viewing images or image-based conditions, or in conditions of

not using a mobile phone while driving. Image-based mobile phone use is a safe

way to stay connected with information via mobile phones while driving. Lady and Susihono

(2019) examined the use of e-maps on smartphones while driving and calculated the

increase probability of a traffic accident use the Human Error Assessment and

Reduction Technique (HEART); the result of human error probability was 0.0106.

According to the drivers’ reports, they never experience accidents, but

sometimes another driver warns them because they inhibited the traffic.

According to Sucha, Sramkova,

and Risser (2014), there are some factors causing aberrant behavior in driving: dangerous

violations; dangerous errors; and not paying attention to driving,

straying, and loss of orientation. Included in the dangerous violation category

is the act of intentionally breaking the rules. Dangerous errors a type of

violation that involves absentminded of the driver. Driver Behavior

Questionnaire (DBQ) divides driving

offenses based on

the level

of awareness

of the

driver making the

offense. This questionnaire is already

used to survey driving behavior in various countries. Research by Harrison

showed high level of internal consistency for each item scales in the DBQ, and

the results support the use of the DBQ as a questionnaire outcome measure in an

evaluation study (Harrison, 2009). Researchers from several

countries showed that the DBQ had a high level of validity and reliability. The

translation of the DBQ is also addressed by Harrison (Harrison, 2009) this questionnaire shows a

high level of reliability when translated into Finnish and Dutch.

The use of e-maps in the form of Global Positioning System (GPS)

navigation can improve the driver performance (Cochran and Dickerson, 2019), (Dickerson, 2020), but also interferes the driver concentration. Higher interference is

experienced when driving in urban areas (Yared and Patterson, 2020), and

using small GPS displays also add distraction to drivers. Interference due to

the use of GPS navigation can cause eye glances and decrease driving

performance (Jensen,

Skov, Thiruravichandran, 2020). The impact of using e-maps

on driver performance has not been specifically studied. Driving distractions

due to the use of mobile phones should be considered for driving safety when

using the e-map. The hypothesis in this study is the increase use of e-maps

while driving is suspected to disrupt driver concentration as well as the use

of mobile phones while driving and resulting in an increase in driving

violations. The a of the research is to

evaluate the psychological effects of using e-maps while driving

on driver, analyzing the effects of using e-maps while driving on driver

involvement in adverse event, identify types of aberrant

behavior of drivers and analyze the factors that cause drivers to make

violations.

This

study analyzed the driving conditions experienced by drivers while driving

using an e-map. The study also identified drivers’ violation habits while

driving. Driver involvement in adverse event and habits of violations were

obtained from respondent answer based on their experiences.

2.1. Respondents

Respondents of this study were passenger car drivers who lived in several

cities in Indonesia. Respondents included men and women with an age range

between 18 and 66 years old. All respondents were confirmed to have a driver’s

license, have more than six months of driving experience, and have used e-maps

via mobile phones while driving.

Some questionnaires

were given

directly to the respondents

and for

others respondent who lived in

different cities from

researcher, the questionnaires distributed through

google form.

There were 325 respondents who filled out the questionnaire, but 5

questionnaires were not processed further because the respondents had never

used an e-map while driving. There were 72.31% male respondents and 27.69% female respondents

in the research.

2.2. Research Location

The

dissemination of questionnaires was conducted in several cities in Indonesia. The data illustrated driving habits and e-map use in developing countries with

heavy traffic, limited pedestrian facilities, and lack of public transport. Many people

in Indonesia prefer to use passenger cars for transportation rather than public

transport because the availability of mass transportation is still limited and

the level of service is still need to be improved. The public transport trips within the cities have not

yet been integrated from origin to destination.

2.3. Questionnaire

The

questionnaire consists of three parts. The first section contains respondent

data covering age, gender, education level, length of driving experience, city

of residence, and ownership of a driver’s license. The second section contains

some questions about the effects of using e-maps on incidents and accidents

that the driver has experienced while driving. According

to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE, 2004) there are two adverse events in accident investigations, namely incidents

and accidents. Two types of incidents are near-miss accident and undesired

circumstance. A near-miss is a condition that has the potential to cause injury

but which has a short interval of time separating it from being an

accident. An undesired circumstance is a

set of conditions or circumstances that have the potential to cause injury such

as changing lines or slowing down suddenly. An accident is a condition that

results in losses for all parties involved in the accident, including the

driver, the system, and the company in which the accident occurred.

The

third section is questions about driving

habits. The questions in this section developed from the Driver Behavior Questionaire (DBQ).

The DBQ is a self-report questionnaire developed as a measurement of aberrant

driving behaviors (Eliou and Misokefalou, 2014; Sucha Sramkova, and Risser, 2014). The

questions in the questionnaire compiled by grouping drivers’ aberrant behavior

into four types of wrong driving habits: errors, lapses, violations, and

aggressive violations. The main distinction between these four types involves

were the degree of planned action and conscious decision making. Errors

characterized by unplanned actions. Lapses are aberrant behavior regarding

failure to pay attention to traffic and recall failure. Violations are aberrant

behavior which the driver intentionally and consciously done. DBQ uses a

six-point Likert scale (1=never; 2=hardly ever; 3=occasionally; 4=often; 5=

frequently; 6=nearly all the time) (Sucha Sramkova, and Risser, 2014; Martinussen et al., 2013). Likert scale with even numbers rather than Likert scale with odd numbers

of choices, because the Likert scale with odd number of choices give respondents

a choice of neutral answers. Respondents were asked to answer

any misconduct statements according to their tendencies.

2.4. Data Processing

The first stage of data processing was to calculate the percentage of

each adverse event experienced by respondents.

The assessment was carried out on aberrant behavior of respondents and tested the difference

between groups of

respondents. The respondents were grouped by

gender and their

experience in adverse

event. Male and female

have different

daily activities

tendencies, male often

involved more to outdoor

activities compared to female. Reaction time recorded by men was significantly faster than

women (Jain et al., 2015; Lipps, Galecki, and

Ashton-Miller, 2011). High frequency of activity

in outdoor

affects the speed

of a

person's movement so

it is

suspected that this

condition also affects the driving agility and the level of

involvement of both

groups of respondents

in undesirable

conditions while driving. A person's habits is influenced by the motivation to act safely or

unsafely manifested in all of

their activities (Hendratmoko, Guritnaningsih,

and Tjahjono, 2016). The

differences in the

involvement of the

two groups

of drivers

in undesirable

conditions were statistically

tested using two

tails of

t-test. It was

found that

there were

differences in driving

experience in adverse

event based on person’s behavior. Linear

regression was used to

see if

aberrant behavior had an

effect on driver

involvement in adverse

event.

Respondents

independently reported their experiences of driving. Some respondents claimed

to have been involved in adverse event. Regression

analysis was

used to describe the effects of using e-maps while driving on respondents’

involvement in adverse event.

3.1. Effects of Using

E-maps while Driving

Aberrant

behavior was done by some of drivers who used e-maps while

driving. Sometimes the aberrant behavior were caused of the

drivers lack of concentration on the traffic. The effects of using e-maps on

driver performance were assessed on four types of adverse event: the frequency

of driver involvement in a near-miss accident condition, frequency of

driver

involvement in an undesired circumstances such as changing lines or slowing

down suddenly and got horns from

other drivers, frequency of driver involvement in an accident, and

increased traffic violations. Driver involvement in a near miss condition was quite

high, at 20.00% of the respondents have involved in range of frequency

from hardly ever until often. Data the effects of using e-maps on driving experiences

is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 The effects of using e-maps on

driving experiences

An

analysis of driver reports due to e-map use while driving found it had an

effect on the increase in traffic accidents. A total of 3.69% of respondents

reported being involved in an accident while using an e-map.

An accident

is a terrible event that inflicts material harm on the person involved and the

system in which the person works. The use of e-maps while driving has a

considerable effect on increased driver involvement in near-miss and undesired

circumstances and a lower effect on increased accidents.

Although the

use of e-maps while driving had a low effect on traffic accidents, it caused

more traffic disruptions, as 20% of respondents had involved in near-miss and

45.54% of respondents reported involved in undesired circumstances and getting

horns. Some secondary tasks cause drivers to not pay attention to the traffic,

such as not giving signal when turning or changing lanes, driving at

slower speeds, or reacting more slowly. Not focusing while driving makes

drivers involved in undesired circumstances. Traffic violations are

intentional and conscious acts by the drivers, 32.62% of respondents felt they

had made traffic violations at an increased rate while driving and using

e-maps.

Some

respondents said they had been involved in one or two adverse event, even some

of other respondents said they had experienced in all these adverse events. But on the other hand 39.94% of

respondents stated that they had never been involved in any adverse event. When driving using e-map, they never

experience incident, accident,

and they also have not done traffic violations.

3.2. Driver Behavior

Respondents

reported their wrong driving habits through the statements in the

DBQ. There are 8 questions in each group of error and lapse, and there are 6

questions in each group of violations and aggressive violations.

Table 2 gives

information about the average of respondents’ answers about four types of

aberrant behavior while driving.

Table 2 Average driver aberrant behavior while driving (in a six-point Likert scale)

The research identified two groups of drivers which based on

gender and their experience involved in adverse event while driving using e-maps. Two

groups of drivers based on their experience involved in adverse event were the

group who had involved in and who had never

been involved in any of adverse event. The first group said they

had been involved in near-miss condition, undesired

circumstance, accident, or made an increase of traffic violations. And

the second group had never

been involved in any of undesirable conditions.

The error

and lapse group were characterized by accidental aberrant behavior. The error

includes ignoring the speed of other vehicles when overtaking,

not using the rearview mirror when

switching lanes, forget to give signal, and braking too fast. Included in the

lapse group are driving equipped with the wrong gear, making driving mistakes

on certain roads, forget to turn on the turn signal. The violation and

aggressive violation group was deliberate actions. The violations such as

speeding and crossing red lights and aggressive violation involve aggression

towards other road users, for example, sounding the horn to display aggression,

to drive on the roadside to avoid traffic jams, and showing resentment.

Male and female groups have the same level of frequency of

making errors and lapses when they drive. However, males are significantly more

likely to do violations (a=0.00) and aggressive violations (a=0.014) than

females. Both violations and aggressive violations are intentional and

conscious acts done by the drivers to achieve their specific aims while

driving. Some groups of men are impatient with the characteristics of other

drivers, want to to drive at high speeds, driving emotionally, and so on.

Driver

behavior in both groups of experience in incidents and

accidents are compared and found the level of aberrant

behavior were higher on the group who had involved in adverse event.

The lapse

group was the most aberrant behavior that drivers made when they

drove using e-maps. A lapse is a mistake caused by forgetting or not knowing

about something; it is an accidental act by the driver in facing traffic

conditions.

3.3. Influence of Driving Habits on Driving Irregularities when

Using E-maps

Daily driving

habits

influenced the driver behavior while driving using e-maps. Four

groups of aberrant behavior in driving: errors, lapses, violations, and

aggressive violations were partially tested their

difference between the groups of drivers involved and never involved in adverse events. The t-test output on each type of

aberrant behavior as the significance value (a) presented

in Table 3.

Table 3 Difference of drivers’

habits on groups of drivers had involved in adverse event

The aberrant behavior that drivers show in daily driving and their

experience when they drove using e-maps are closely related. Statistical analysis using t-tests was partially conducted between two groups

of drivers based on their experience driving using

e-map. There was a significant difference in the level of

aberrant behavior between groups of drivers who were involved in adverse event and those

who never get involved.

Significant differences were found in the four types of driving habits (a=0.000

for all of aberrant behavior type: error, lapse, violation, and aggressive

violation). The aberrant

behavior of group that had been involved in adverse event when using e-maps was higher than those who does not get

involved in adverse event.

The involvement of adverse event when using e-maps occurred in

groups of drivers who had aberrant behavior, meanwhile

there was no involving in adverse event while driving using e-maps on drivers who had good behavior. Groups with aberrant behavior will do traffic violations easily

when using e-map, meanwhile groups that have good behavior will still follow the traffic

rules. The driver who use an e-maps while driving will not hampere the traffic

because the compliant driver will still run

the traffic rule even when using the e-map, so there will not be a traffic

violations increasement. The increase in

violations only occured by the drivers who have aberrant

behavior in daily driving, so it is necessary to improve the aberrant behavior of drivers

in driving.

Regression analysis was conducted on the driver involvement in adverse

event as dependent variables and the aberrant behavior of errors, false,

violations, and aggressive violations as independent variables. The output of

the regression analysis was multiple R = 0.48, which explains the relationship

between dependent variables involvement in adverse event and independent

variables at the moderate level.

The Planned Behavior Theory describes a person's habits

influenced by the intention to perform an action. This theory is used as the

basis for how a person does aberrant behavior and unsafe actions in driving (Hendratmoko,

Guritnaningsih, and Tjahjono,

2016). Intention represents someone's motivation to act safely or unsafely

that consciously planned to do. Intentions formed by three variables: attitude,

subjective norm, and perceived behavior control. Attitude is defined as the

positive or negative beliefs to display a certain behavior; Subjective Norm is

a person's perception of the social pressure to perform or not perform the

behavior; and Perceived Behavior Control described as the perception of the

behavior of ease or difficulty. The intention to

perform an action

in this

case can

be seen

from the

motivation of drivers

to act

unsafely which indicated by the high

frequency of aberrant behavior

carried out by

them.

Lowering the negative effect of using e-maps on safety in driving could

be done in two approaches. The first approach was by focused on the driver.

Driving safety is influenced by the intention of each individual to act safe or

unsafe. Driving safety could be achieved through individual approaches by

improving the basic human values and risk perception of the individual (Sutalaksana, Zakiyah, and Widyanti, 2019).

Increased driver discipline in driving and driver knowledge of traffic rules

was the first solution. The second approach was carried out to the process of

using e-maps in driving, by creating a Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) for

using of e-maps. The SOP

explains the steps

taken by

drivers in two stages:

the preparation

stage for

using e-map

and the

driving stage.

Using e-maps while driving decrease the drivers’

performance and increase their involvement in adverse event in some drivers. As many as 45.54% respondents said they have involved in undesired circumstance in range of frequency from hardly ever until

often. As many as 32.62% of respondents said they have made increasing violations and 20% of respondents have involved in a near-miss condition. On the other hand, as many as 39.94% of respondents stated they had never been involved in

any adverse event. Aberrant behavior and the drivers’ involvement in adverse event have a medium

correlation. Involvement in adverse event experienced by the wrong habit of drivers. Drivers who have never been

involved in adverse event when using e-maps have a good traffic habit. The use of e-maps by good habit drivers didn’t impede the traffic. In order of using e-map not to interfere with traffic, it is necessary to increase awareness of drivers

who have aberrant behavior in driving.

Thank you for assistancing in collecting data

for assistants of Ergonomics and Work Design Laboratorium in 2020, University

of Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa - Indonesia.

Allahyari, T., Saraji, G.N., Adi, J., Hosseini,

M., Iravani, M., Younesian, M., Kass, S.J., 2008. Cognitive Failures, Driving Errors and Driving Accidents. International Journal of

Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, Volume

14(2), pp. 149–158

Cochran, L.M., Dickerson, A.E. 2019. Driving While Navigating: On-Road Driving Performance Using GPS

or Printed Instructions. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Volume

86(1), pp. 61–69

Dickerson, A.E., 2020. Use of GPS for Older Adults to Decrease Driving Risk: Perceptions From Users and Non-Users. Geriatrics Volume 5(3), p.

60

Eliou, N., Misokefalou, E., 2014. Comparative Analysis of Drivers’

Distraction Assessment Methods. In: 22nd

ICTCT Workshop, Towards and Beyond the, pp. 1–9

Harrison, W., 2009. Reliability of the Driver Behaviour Questionnaire in a Sample of

Novice Drivers. In: Proceedings of the Australasian Road Safety

Research, Policing and Education Conference. Volume 13, pp. 661–675

Hendratmoko, P., Guritnaningsih, Tjahjono, T., 2016. Analysis

Interaction Between Preferences and

Intention for Determining the Behavior of Vehicle

Maintenance Pay as a Basis for

Transportation Road Safety Assessment. International Journal of Technology, Volume (7)1, 105–113

Health and Safety Executive (HSE), 2004. HSG245: Investigating Accidents and Incidents. Health and Safety Executive. Available online

at: https://www.hse.gov.uk /pubns/hsg245.pdf , accessed on June 15, 2022

Hurts, K., 2011. Driver Distraction, Crosstalk, and Spatial Reasoning. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, Volume 14(4), pp. 300–312

Jain, A., Bansal, R., Kumar, A., Singh, K.D., 2015. A Comparative

Study of Visual And Auditory Reaction Times on The Basis of Gender znd

Physical Activity Levels of

Medical First Year Students. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research, Volume 5(2), pp. 124–127

Jensen, B.S., Skov, M.B.,

Thiruravichandran, N., 2010. Studying Driver Attention and Behaviour for Three Configurations of GPS Navigation in Real Traffic Driving. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1271-1280

Kaber, D.B., Liang, Y., Zhang, Y., Rogers,

M.L., Gangakhedkar, S., 2012. Driver Performance Effects of Simultaneous Visual and Cognitive Distraction and

Adaptation Behavior. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, Volume 15(5), pp. 491–501

Lady, L., Susihono, W., 2019. Effect of

Using Electronic Map While Driving on

Human Error Probability. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and

Operations Management,

pp. 1464–1473

Lipps, D.B., Galecki,

A.T., Ashton-Miller, J.A., 2011.

On the implications of a sex difference in the reaction times of sprinters at

the Beijing Olympics. PLoS ONE, Volume 6(10), pp. 4–8

Martinussen, L.M., Hakamies-Blomqvist, L.,

Moller, M., Ozkan, T., Lajunen, T., 2013.

Age, Gender, Mileage and the DBQ: The Validity of the Driver Behavior

Questionnaire in Different Driver Groups. Accident Analysis and Prevention, Volume 52, pp. 228–236

Mcnabb, J., Gray, R., 2016. Staying Connected on the Road?: A Comparison of Different Types

of Smart Phone Use in a Driving Simulator. PLoS one, Volume 11(2), pp. 1–13

Misokefalou, E., Papadimitriou, F., Kopelias,

P., Eliou, N., 2016. Evaluating Driver Distraction Factors in

Urban Motorways. A Naturalistic Study Conducted in Attica Tollway, Greece. Transportation Research

Procedia,

Volume 15, pp. 771–782

Oviedo-Trespalacios, O., King, M., Haque, M.M., Washington, S., 2017. Risk Factors of Mobile Phone Use While Driving in Queensland?:

Prevalence, Attitudes, Crash Risk Perception, and Task-Management Strategies. PLoS One, Volume

12(9), pp. 1–17

Owens, J.M., McLaughlin, S.B., Sudweeks, J., 2011. Driver Performance While Text Messaging

Using Handheld and

In-Vehicle Systems. Accident Analysis and Prevention, Volume

43(3), pp. 939–947

Prat, F., Gras, M. E., Planes, M., Font-Mayolas,

S., Sullman, M.J.M., 2017.

Driving Distractions: An Insight Gained From Roadside Interviews On Their

Prevalence And Factors Associated With Driver Distraction. Transportation Research

Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, Volume

45, pp. 194–207

Rodrick, D., Bhise, V., Jothi, V., 2013. Effects of Driver and Secondary Task

Characteristics on Lane Change Test Performance. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries, Volume 23(6), pp. 560–572

Sucha, M., Sramkova, L., Risser, R., 2014. The Manchester Driver Behaviour

Questionnaire: Self-Reports of

Aberrant Behaviour Among Czech Drivers. European Transport Research Review, Volume 6(4), pp. 493–502

Sutalaksana, I.Z., Zakiyah,

S.Z.Z., Widyanti, A., 2019.

Linking Basic Human Values, Risk Perception, Risk Behavior and Accident Rates: The Road To Occupational

Safety. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 10(5), pp. 918–929

Van-Dam,

J., Kass, S.J., VanWormer, L., 2020. The Effects Of Passive Mobile Phone

Interaction On Situation Awareness and

Driving Performance. Journal of Transportation Safety and Security, Volume 12(8), pp. 1007–1024

Yared, T.,

Patterson, P., 2020. The Impact of Navigation System Display Size and Environmental Illumination on

Young Driver Mental Workload. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, Volume 74, pp. 330–344

Young, K.L., Salmon, P.M., 2012. Examining The Relationship Between Driver

Distraction and Driving Errors: a Discussion of Theory,

Studies and Methods. Safety Science, Volume

50(2), pp. 165–174

Zuraida, R., Iridiastadi,

H., Sutalaksana, I.Z., 2017.

Indonesian Drivers Characteristics Assiciated With Road Accidents. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 8(2), pp. 311–319

Zuraida, R., Wijayanto,

T., Iridiastadi, H., 2022.

Fatigue during Prolonged Simulated Driving: An Electroencephalogram Study. International Journal of

Technology, Volume 13(2), pp. 286–296