Preparation and Characterization of Curcumin-Based Coating Material on Co-Cr Alloy

Corresponding email: budyuls@ugm.ac.id

Published at : 25 Jan 2024

Volume : IJtech

Vol 15, No 1 (2024)

DOI : https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v15i1.3588

Roza, F.N., Herliansyah, M.K., Setianto, B.Y., Githanadi, B., 2024. Preparation and Characterization of Curcumin-Based Coating Material on Co-Cr Alloy. International Journal of Technology. Volume 15(1), pp. 18-27

| Faizatin Nadya Roza | Biomedical Engineering Study Program, The Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia |

| Muhammad Kusumawan Herliansyah | Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia |

| Budi Yuli Setianto | Department of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia |

| Brillyana Githanadi | Biomedical Engineering Study Program, The Graduate School of Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia |

Co-Cr; Coating; Curcumin; PLLA

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the most

considerable health problems which can be the leading cause of death worldwide (Khan et al., 2020). It is

caused by the narrowing of blood vessels or other

abnormalities, primarily due to plaque formation known as atherosclerosis,

which can lead to a heart attack. Atherosclerosis can be overcome by installing

a stent. Stent aims to support the coronary vessel wall so it does not easily

recoil after being dilated with a balloon (Grabow et al., 2010). It

is mostly made of metal such as stainless steel, platinum alloys-chromium (Jorge and Dubois, 2015), or

cobalt-chromium (Co-Cr), then formed into a small pipe, originally known as

bare metal stent (BMS). Co-Cr alloys have high density, which is

advantageous to radio-opacity, and have high elastic modulus, which limits

recoil, and tensile strength properties that allow stent designs with thinner

struts (Poncin et al., 2005).

Besides

the promising role of Co-Cr stents for minimization of coronary remodeling,

restenosis risk remains a critical concern. Restenosis could occur due to blood

clotting, called thrombosis, which can lead to the proliferation of vascular

smooth muscle cells (VSMC) (Foerst et

al., 2013). Besides the promising role of Co-Cr stents for the

minimization of coronary remodeling, restenosis risk remains a critical

concern. Restenosis could occur due to blood clotting called thrombosis,

leading to the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) (Foerst et al., 2013).

The

VSMC proliferation and intracellular matrix synthesis in response to

stent-implanted inflammatory reaction are broadly believed as the major

mechanisms of restenosis, and it needs a drug to prevent it (Bennet and

Michael, 2001). However, orally administered drugs may have inadequate

local drug concentration and can cause toxic reactions from excessive drug

doses. Therefore, a drug delivery system is needed to control drug release (Imani et al.,

2022). The drug delivery system works by preserving the drug

and restraining the drug release; therefore, the drug can reach its action site

appropriately by enhancing and/or reducing the drug circulation (Barleany et al.,

2020). To deal with this issue, drug coating stents which are

globally known as drug-eluting stents (DESs), become the answer by releasing

pharmacological agents to inhibit the response of restenosis (Bennet and Michael,

2001).

Previously,

DES, which releases anti-proliferative drugs such as sirolimus (rapamycin) and

paclitaxel with synthetic polymer

coatings, has opened up a new paradigm for the treatment of in-stent restenosis

(ISR), known as first-generation DES. Advantageously, these drug-coating stents

can provide luminal scaffolding that eventually eliminates the recoil and

remodeling of vascular coronary. However, the released drug from the coating

can achieve high local drug concentration, cellular proliferation prevention,

or thrombus formation (Waksman et al., 2006).

Furthermore, the residual synthetic polymer coating remains in the body, which

may lead any complications such as an over-inflammatory response and neointimal hyperplasia at the implant

site (Ranade

et al., 2004). To avoid these unavailing effects, it is

urgent to build a drug-coating stent with a biodegradable and biocompatible

coating. One kind of biodegradable polymer that has good mechanical properties

is Poly-(L lactic acid) (PLLA). This polymer is known to be the most desirable

biocompatible and biodegradable polymer obtainable from starch in a high yield (Ni’mah et al., 2019). PLLA is

widely used in biomedical devices such as orthopedic surgery and other surgery

fields where bioresorbable sutures are needed, as well as used for

drug-delivering implants (Zilberman

and Eberhart, 2006). Because of its superior mechanical strength,

PLLA can be a good candidate as a drug carrier for stent coatings.

Curcumin

is a polyphenolic compound commonly

derived from the dried rhizomes of Curcuma

longa L. (Basile

et al., 2009), presents low intrinsic toxicity and shows a

wide spectrum of pharmacological properties, including anti-oxidation,

anti-inflammation, anti-thrombus and anti-proliferation activities (Chen et al.,

2015). These promising characteristics suggest that curcumin could be applicable as a

therapeutic agent for DES.

By considering these biomaterials, the

preparation of the curcumin-based coating using Poly-(L lactic acid) (PLLA) as

the drug material, along with the in vitro characteristics in this study, were

reported. To our knowledge, the preparation of curcumin coating by using PLLA to be coated on Co-Cr alloy has not

been investigated.

2.1. Materials

The material used in this study was Co-Cr alloy

(Dentaurum GmbH & Co. KG, Ispringen, Germany). The composition (wt%), as

provided by the manufacturer, was 60.5% cobalt

(Co), 28% chromium (Cr), 1.5% silicon (Si), 9% tungsten (W), other elements were manganese (Mn), nitrogen

(N), niobium (Nb), and iron (Fe) were less than 1%, and free

from nickel (Ni), beryllium (Be), and gallium (Ga). The coating material was curcumin (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt,

Germany) that had a purity above 96% and PLLA (30% wt. in H2O)

(L1875–Sigma Aldrich, Massachusetts, US). All other reagents used in this

research were analytical grade.

2.2. The Curcumin-based Coating Preparation

Firstly, the Co-Cr tube was shaped into a platted disk by a mold casting

machine. The materials were polished and then were cleaned ultrasonically with

acetone (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), ethyl alcohol (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt,

Germany), and distilled water sequentially. The cleaned materials were

preserved under a vacuum to evaporate the residual water (Pan et al., 2006). Next,

curcumin, which was previously dissolved in absolute ethanol at different

concentrations, was mixed with 1% wt. of PLLA using a homogenizer for at least

3 minutes. The solutions were then sprayed onto cleaned materials using the

ultrasonic spraying method, with each sample sprayed for at least 1 minute. It

was remarked parenthetically that the solutions sprayed to all samples were

about 0.5 ml with about 3µm thickness of the coating severally. Those sprayed

mass of coating on the sample surface could be obtained by calculating the

solution concentration. Three coating concentrations of curcumin were prepared at low concentration (~62.5 µg), moderate

concentration (~125 µg), and high concentration (~250 µg). There were two kinds

of control samples prepared. The first one was with only polymer, and the

second one was with curcumin with the

same concentration and the same method of coating.

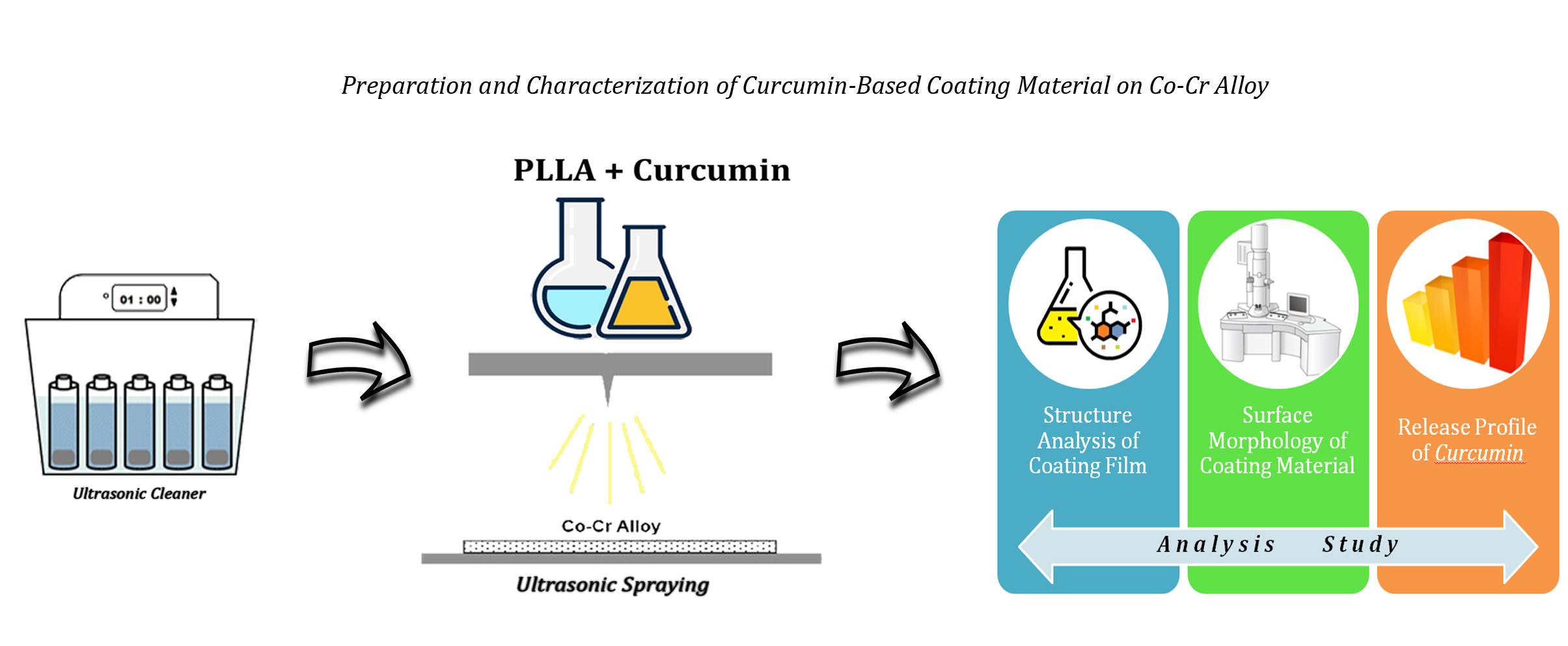

Figure 1 Schematic of Material Preparation using

Ultrasonic Cleaner and Ultrasonic Spraying

2.3. Fabrication of the coating films

To cast a thin polymer film, a one wt.% solution PLLA

was prepared by dissolving the solution in ethyl acetate (Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany), then placed on a cleaned watch glass dish 10 cm. The films

were slowly dried in hot air until the solvent evaporated to obtain the films.

The films were then preserved to evaporate the residual solvent. The curcumin

coating films were prepared in two different ways. First, curcumin with high

concentration dissolved in ethanol was mixed with dissolved PLLA in ethyl acetate,

and the second was dissolved curcumin in ethanol only. Both of them were

evaporated and were treated in the same manner as such polymer films.

2.4.

Structure analysis of the coating films

The structure of PLLA, curcumin, and curcumin/PLLA

films was analyzed by the FTIR system (FTIR type SHIMADZU IR-Prestige 21,

Japan) to determine the chemical compounds. Further, curcumin powder was also

examined for additional control data. The scanning of the FT-IR range equipped

with an attenuated total reflectance accessory for wavenumbers from 4,000 cm-1

to 300 cm-1, approximately 20 scans were performed for each film

with 1 cm resolution.

2.5.

Morphology of curcumin-based coating

The surface morphology of curcumin-based and PLLA

coatings was investigated using analytical scanning electron microscopy

(SEM-EDX JEOL JSM-6510LA, JEOL Ltd., Japan), operated at SEI with 20 kV

accelerating voltage. In addition, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)

analysis was also performed to determine the abundance of the specific chemical

elements of each sample.

2.6.

Curcumin

Release Profile

The release profile of the curcumin from the samples

was examined in vitro by immersing each sample in a medium consisting of

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.4) (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Massachusetts, US) with 10% ethanol at 37OC because the

solubility limit of the curcumin in water that makes it difficult to be

investigated in buffer (Alexis et al., 2004). At specific intervals, the medium of the PBS solution

was removed completely and replaced with the fresh medium. The removed medium

was then measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (VWR®V V-1200,

UV–1600PC Spectrophotometer UV-Vis, England) at wavelength 425 nm to determine

the amount of released curcumin. The results were obtained accumulatively in

micrograms (µg) and percentages (%) of released curcumin. Moreover, in order to

investigate the drug release mechanism, it was applied by using the equation of

Ritger & Pappas (see Equation 1) as below:

where Mt was the amount of curcumin released at the time (t), was the total amount of curcumin, and k was a constant parameter of the

release exponent (Kharaziha et al., 2015).

3.1. FTIR Analysis

FTIR spectra of curcumin, PLLA, curcumin coating film, and curcumin/PLLA coating film are shown in Figure2. A transmission band related to curcumin was observed at 3448 cm-1. This was attributable to the stretching vibrations of the phenolic O-H group. However, this band could not be distinguished from other peaks in curcumin coating film and so curcumin/PLLA coating film. A sharp peak was seen at 1597 cm-1, corresponding to the stretching of the C = C bond of the benzene ring. Another sharp peak was seen at 1512 cm-1. It was related to the olefin bending vibrations of the C-H bond to the benzene ring of curcumin. Those peaks were shifted to 1620 cm-1 and 1520 ccm-1, respectively, in curcumin coating film, as well in curcumin/PLLA coating film to 1589 cm-1 and 1517 cm-1, respectively. Further, the peak from pure curcumin at 817 cm-1 and 1280 cm-1, assigned for vibration of C–O in –C–OCH3 of the phenyl ring, were shifted and only detected at 1288 cm-1 in curcumin coating film and at 1285 cm-1 in curcumin/PLLA coating film.

Figure 2 Result of

the FTIR Analysis of Pure Curcumin and PLLA, Curcumin Film, and Curcumin/PLLA

film

Similarly, with the curcumin-related band, a

valley-like peak at 3425 cm-1 was seen in PLLA film. This was

probably ascribable to hydroxyl stretching OH bending. Other characteristic peaks of PLLA and their shift in

curcumin/PLLA were also identified. A blunt peak at 1628 cm-1 is

assigned as carbonyl stretching C=O in the –CO–O– group of PLLA and was

observed vaguely at 1728 cm-1 at curcumin/PLLA. Another hollow-like

peak was seen at 1180 cm-1. This corresponds to the stretching

vibrations of the symmetric CH bending in the –CH–O– chains of PLLA, and it

shifted to 1141 cm-1 in the case of curcumin/PLLA. Additionally, a

mountainous triplet peak at 1033; 956; and 879 cm-1 that were

ascribable to the C–O bond vibration in –CO–O– group in PLLA chains shifted

accordingly to 1026; 934; and 848 cm-1 respectively in

curcumin/PLLA.

Based on

the peak shifts shown in the FTIR data (Figure 2), it can be confirmed that

curcumin and PLLA were adequately bound together. Meanwhile, the peak at 879 cm-1 in PLLA, which was ascribable to the C–O bond vibration in the –CO–O– group in

PLLA chains, shifted to 848 cm-1 in curcumin/PLLA. That shifting could be confusing with the vibrations

of the phenyl ring C–O in –C–OCH3 from curcumin. Nevertheless, this confusion can lead to the certainty

that curcumin and PLLA were perfectly

blended. Furthermore, a peak at 1628 cm-1 that was identified as

carbonyl stretching C=O in the –CO–O– a group of PLLA then shifted to 1728 cm-1 at curcumin/PLLA, indicating weak

hydrogen bond formation between the carbonyl group of PLLA and the hydroxyl

group of curcumin. This finding was

reinforced by the peak shift of the symmetric CH bending of PLLA in curcumin/PLLA, from 1180 cm-1 to 1141 cm-1. C–H groups that showed symmetric CH bending were the

neighboring groups to C = O in PLLA. The changes in vibrational frequency indicated

by the peak shift were probably the consequence of interaction between the C = O

group of PLLA with the O–H group of curcumin.

3.2. SEM-EDS Analysis

SEM images were taken

on the top surface where curcumin, curcumin/PLLA, and PLLA were coated on

Co-Cr Alloy. Those images are shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5 to

evaluate the morphology of the coating. There are two types of analyzed samples

for SEM, first, the samples that were only coated with curcumin, curcumin/PLLA,

and PLLA on Co-Cr Alloy, and the second were the coated samples with release

treatment with PBS (phosphate buffer saline) for about 20 hours.

Figure 3 SEM Images of curcumin coated before (A) and after (B)

PBS treatment

Figure 4 SEM Images of PLLA

coated before (C) and after (D) PBS treatment

Figure 5 SEM Images of curcumin/PLLA coated before (1, 3)

and after (2, 4) PBS treatment

A

considerably smooth surface was observed on the surface where the sample was

coated with PLLA only. It could be indicated that the PLLA was coated perfectly

with Co-Cr. However, after giving the release treatment with PBS, it was shown

that the PLLA surface formed some cuboid shape particles that claim the PLLA

surface has a deformation on its particles. On the other hand, A rough surface

with circular shaped particles was seen on a sample that was coated with curcumin only. It is indicated the distribution

of the curcumin particle on the

material surface. Further, a fractured surface was then observed after the

coating was treated with PBS. At fractured surface condition shows that the curcumin was released and formed a

deformation on the surface. Surprisingly, on the SEM images of the

curcumin/PLLA coated surface revealed the presence of numerous tubular-shaped

particles on the surfaces. Those deformations on curcumin/PLLA particles could be caused by the adsorption of the curcumin onto PLLA. curcumin/PLLA coating surface after treatment with PBS.

In the

other images of the curcumin/PLLA

coatings, there was a sloughed area on the coated sample surface which was

treated by PBS. Those indicated that the curcumin/PLLA

coating which was treated by PBS, was released well at almost one day of

releasing time. In addition, it can be vaguely seen that there were some

shrinking particles on the Table 1.

Table 1 Element composition (wt%), measured using

energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), of the surface of the cobalt-chromium

(CoCr) alloy coated with PLLA, Curcumin,

and Curcumin/PLLA

|

Sample Treatment |

Element Composition Mass (wt.%) |

| ||||||

|

Co |

Cr |

W |

Si |

C |

H |

O | ||

|

PLLA Coating |

53 |

26 |

8 |

1 |

9 |

0 |

2 | |

|

Curcumin Coating |

40 |

19 |

6 |

1 |

28 |

0 |

6 | |

|

Curcumin/PLLA Coating |

39 |

20 |

7 |

1 |

27 |

0 |

5 | |

The result of the surface topography of the coated

specimens analyzed using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was barely

perceptible in the spectrum images of EDS analysis (data was not shown). In

spite of the spectra analysis of the EDS, the result of the element composition

mass of the specimens had some differences discernibly. On the top surface of

the PLLA coated specimen, the composition mass of the Co-Cr alloy such as Co,

Cr, W, and Si was the highest among other coating treatment samples. It could

be argued that the PLLA coating film on Co-Cr alloy only slightly affect the

element composition of the material. However, on the curcumin-only coating and curcumin/PLLA

coating, there were obviously increments in the composition of the coating

elements. Among the three specimens, the curcumin/PLLA

coating sample had the lowest amount of mass of the Co-Cr element composition,

whereas the curcumin coating sample

had the most sizeable amount of coating composition of elements. The coating

elements, which were C, H, and O, were adapted from curcumin (C21H20O6) and PLLA (C3H6O3)

3.3. The Release Profile of Curcumin

Figure 6 In vitro release profile of curcumin from three concentration types

of coated materials; the cumulative amount of curcumin

Figure 7 In vitro release

profile of curcumin from three

concentration types of coated materials; the percentage weight of released curcumin

The release of the

drug from the matrix paired with the polymer begins with the presence of an

initial burst release (Dinarvand et al., 2005). Therefore, tests were carried out in two different

types of time intervals, the fast release period in the first hour for 8 hours

after treatment with PBS, then followed by a moderate-slow release period of

observation for 14 days. Based on the results in Figure 6, all specimens coated

with curcumin/PLLA in each treatment

showed a nearly linear controlled-release profile with no significant burst

release observed during the first hour period up to 14 days of the test.

Theoretically, the controlled release of anti-restenosis drugs is required to

prevent the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC)

for at least one month after stenting implantation (Puranik, Dawson, and Peppas,

2013). From the curcumin release profile graph in Figure 6, the average release of

the controlled rate at low concentrations is ±1.42 µg per day (2.27% wt.), at

moderate concentrations ±2.21 µg per day (1.76% wt.), and ±3.03 µg per day

(1.21%) at high concentrations. Furthermore, based on the average rate of curcumin release, it could be decided

that the duration of curcumin-controlled

release is ±44 days for curcumin/PLLA

low concentration, ±57 days at moderate concentration, and for ± 82 days at curcumin/PLLA high concentration. All of

the concentrations overall met the criteria for drug release for at least 30

days (one month). Additionally, the Ritger and Peppas equation (Equation 1) was

also applied to evaluate the mechanism of curcumin

release (Kharaziha et al., 2015). The results showed that the release of curcumin in the curcumin/PLLA

coating in this study occurred through a diffusion mechanism. The treatment of

replacing the release medium at successive day intervals resulted in a

significant gradient of curcumin

concentration between curcumin/PLLA

with the release medium, causing the formation of barely constant linear lines

from the diffusion of the drug, as shown in Figure 6. Diffusion-sustained drug

delivery systems can arrange the delivery of drugs for several weeks and give a

special capability to control the kinetics of drug release (Acharya and

Park, 2006). In addition, the diffusion of

drug molecules through the polymer matrix depends on the solubility of the drug

in the polymer, as well as the medium surrounding the drug as the diffusion

coefficient and concentration gradient of the drug to the polymer. Therefore,

it can provide an indication that if the diffusion of curcumin is faster than the degradation of the polymer matrix, it

means that the mechanism of releasing curcumin

occurs through the diffusion mechanism (Mohammadi et al.,

2019).

In conclusion, based on the

results obtained in this research suggested that curcumin-based coating had the potential to become a coating

material for improving drug-eluting stents. Curcumin

could be blended with PLLA at the molecular level as coating material using

ultrasonic spraying as shown by SEM images. In addition, curcumin could be indicated to disperse in the PLLA matrix

according to FTIR results. Curcumin also can be potential material for

drug eluting stents as it showed the mildly sustained release profile without

any apparent burst release. The slightly drawback of curcumin release

profile which is needed to be reviewed is to find the moderate amount of

curcumin concentration that can be released no more than 30 days in order to

release at the appropriate duration.

This research could be finished and succeeded with

full support from Universitas Gadjah Mada Grants that are Final Assignment

Recognition Grant (RTA 2019) [3142/UN1/DITLIT/DIT-LIT/LT/2019] and University

Excellence Development Research Grant (PPUPT 2018) [1993/UN1/DITLIT/DIT-LIT/LT/2018].

Additionally, a grateful pleasure for Professor Widowati Siswomihardjo and Mr.

Ir. Alva Edy Tontowi, M.Sc., Ph.D. as the Head and Vice Head of Biomedical

Engineering Universitas Gadjah Mada.

| Filename | Description |

|---|---|

| R2-MME-3588-20230614113844.jpg | Result of the FTIR Analysis of Pure Curcumin and PLLA, Curcumin Film and Curcumin/PLLA film. (figure 2 (2) - right) |

Alexis, F., Venkatraman, S.S., Rath, S.K.,

Boey, F., 2004. In Vitro Study of Release Mechanisms of Paclitaxel and

Rapamycin from Drug-Incorporated Biodegradable Stent Matrices. Journal of Controlled Release, Volume 98(1), pp. 67–74

Barleany, D.R., Ananta,

C.V., Maulina, F., Rochmat, A., Alwan, H., Erizal, 2020. Controlled Release of

Metformin Hydrogen Chloride from Stimuli-responsive Hydrogel based on Poly(N-

Isopropylacrylamide)/Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Composite. International

Journal of Technology, Volume 11(3), pp. 511–521

Basile, V., Ferrari, E., Lazzari,

S., Belluti, S., Pignedoli, F., Imbriano, C., 2009. Curcumin Derivatives:

Molecular Basis of Their Anti-Cancer Activity. Biochem Pharmacol, Volume 78(10), pp. 1305–1315

Bennet, M.R., O'Sullivan, M.,

2001. Mechanisms of Angioplasty and Stent

Restenosis: Implications for Design of Rational Therapy. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Volume 91(2), pp. 149–166

Chen, W., Habraken, T.C.J.,

Hennink, W.E., Kok, R.J., 2015. Polymer-Free Drug- Eluting Stents: An Overview of Coating Strategies

and Comparison with Polymer-Coated Drug-Coating Stents. Bioconjugate Chemistry, Volume 26 (7), pp. 1277–1288

Dinarvand, R., Mahmoodi,

S., Farboud, E., Salehi, M., Atyabi, F., 2005. Preparation of Gelatin

Microspheres Containing Lactic Acid—Effect of Crosslinking on Drug Release. Acta Pharmaceutica, Volume 55(1), pp. 57–67

Foerst, J., Vorpahl, M.,

Engelhardt, M., Koehler, T., Tiroch, K., Wessely, R., 2013. Evolution of

coronary stents: From bare-metal stents to fully biodegradable, drug eluting stents. Combination Products in Therapy, Volume 3(1-2), pp. 9–24

Grabow, N., Martin, D.P.,

Schmitz, K.P., Stenberg, K., 2010. Absorbable Polymer Stent Technologies for

Vascular Regeneration. Journal of

Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, Volume 85(6), pp. 744–751

Imani, N.A.C., Kusumastuti,

Y., Petrus, H.T.B.M., Timotius, D., Putri, N.R.E., Kobayashi, M., 2022.

Preparation, Characterization, and Release Study of Nanosilica/Chitosan

Composite Films. International Journal of Technology. Volume 13(2),

pp. 444–453

Jorge, C., Dubois, C.,

2015. Clinical Utility of Platinum Chromium Bare Metal Stents in Coronary Heart

Disease. Medical Devices: Evidence

and Research, Volume 8, pp. 359–367

Khan, M.A., Hashim M.J.,

Mustafa, H., Baniyas, M.Y., Al-Suwaidi, S.K.B.M., Alkatheeri, R., Alblooshi,

F.M.K., Almatrooshi, M.E.A.H., Alzaabi, M.E.H., Al-Darmaki, R.S., Lootah,

S.N.A.H., 2020. Global Epidemiology of Ischemic Heart Disease: Results from The

Global Burden of Disease Study. Cureus, Volume 12(7), p. 9349

Kharaziha, M., Fathi, M.H.,

Edris, H., Nourbakhsh, N., Talebi, A., Salmanizadeh, S., 2015. PCL-Forsterite

Nanocomposite Fibrous Membranes for Controlled Release of Dexamethasone. Journal of Materials

Science: Materials in Medicine, Volume 26(1), p. 36

Mohammadi, F., Golafshan,

N., Kharaziha, M., Ashrafi, A., 2019. Chitosan-Heparin Nanoparticle Coating on

Anodized NiTi for Improvement of Blood Compatibility and

Biocompatibility. International

Journal of Biological Macromolecules,

Volume 127, pp. 159–168

Ni'mah, H., Rochmadi, R.,

Woo, E.M., Widiasih, D.A., Mayangsari, S., 2019. Preparation and

Characterization of Poly(L-lactic acid) Films Plasticized with Glycerol and

Maleic Anhydride. International Journal of Technology, Volume

10(3), pp. 531–540

Pan, Ch.J., Tang, J.J.,

Weng, Y.J., Wang, J., Huang, N., 2006, Preparation, Characterization And

Anticoagulation of Curcumin-Eluting Controlled

Biodegradable Coating Stents, Journal

of Controlled Release, Volume

116(1), pp. 42–49

Poncin, P., Millet, C., Chevy, J., Proft, J.L.,

2004. Comparing and Optimizing Co-Cr Tubing for Stent Applications. In:

Proceedings of Materials and Processes for Medical Devices Conference, pp. 279–283

Puranik, A.S., Dawson,

E.R., Peppas, N.A., 2013. Recent Advances in Drug Eluting Stents. International

Journal of Pharmaceutics. Volume 441(1-2), pp. 665– 679

Ranade, S.V.,

Miller K.M., Richard R.E., Chan, A.K., Allen, M.J., Helmus, M.N.,

2004. Physical Characterization of Controlled Release of Paclitaxel from

the TAXUS™ Express 2™ Drug-Eluting Stent. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Volume 71(4), pp. 625–634

Sternberg, K., Kramer, S.,

Nischan, C., Grabow, N., Langer, T., Hennighausen, G., Schmitz, K.-P., 2007. In

Vitro Study of Drug- Eluting Stent

Coatings Based on Poly(L-lactide) Incorporating Cyclosporine A–Drug Release,

Polymer Degradation and Mechanical Integrity. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, Volume 18(7), pp. 1423–143

Waksman, R., Pakala, R.,

Baffour, R., Hellinga, D., Seabron, R., Kolodgie F., Virmani R., 2006. Optimal

Dosing and Duration of Oral Everolimus to Inhibit In-Stent Neointimal Growth in

Rabbit Iliac Arteries. Cardiovascular

Revascularization Medicine, Volume 7(3),

pp. 179–184

Zilberman, M., Eberhart,

R.C., 2006. Drug-Eluting Bioresorbable

Stents for Various Applications.

Annual Review of Biomedical

Engineering. Volume 8, pp. 153–180